Left atrial appendage occlusion

Summary

Atrial fibrillation is the most common arrhythmia worldwide, with a lifetime incidence approaching 25% and an ever-increasing prevalence in an aging society. It is projected that by the year 2050, 6 to 12% of the world’s population will be diagnosed with atrial fibrillation, and 18 million will be affected in Europe by the year 2060. The most devastating consequences of atrial fibrillation are embolic cerebrovascular accidents. While anticoagulation strategies result in significant reductions in embolic events, they are not without limitations and complications, namely bleeding. In patients with atrial fibrillation, the vast majority of thrombus originates in the left atrial appendage. Exclusion of the left atrial appendage has been demonstrated to be as effective as oral anticoagulation with Vitamin K antagonists in the prevention of disabling strokes and obviates the need for chronic anticoagulant therapy.

The field of transcatheter endovascular left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO) has expanded exponentially since its inception two decades ago and is potentially emerging as the anti-embolic treatment of choice for patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation pending the results of highly anticipated trials. While the Watchman and Amplatzer Amulet devices dominate the transcatheter percutaneous LAAO market shares in both Europe and America, the structural proceduralist will soon be able to choose from multiple device options to accommodate the wide variation of LAA morphologies present in the human population. LAAO devices are currently indicated in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation with contraindications to anticoagulation. While no procedure is risk-free, device iteration has resulted in improved safety and versatility. This chapter reviews the underlying concepts involving atrial fibrillation, outlines anticoagulation strategies for thromboembolism prevention, and describes the current state and future directions of left atrial appendage occlusion.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation is an extremely common condition with a prevalence of approximately 0.4% and a strong association with age and male sex. The age-adjusted incidence approaches 5% per year in patients greater than 80 years of age, and prevalence in this population is approximately 9%. The lifetime risk of developing atrial fibrillation is approximately 1 in 4.

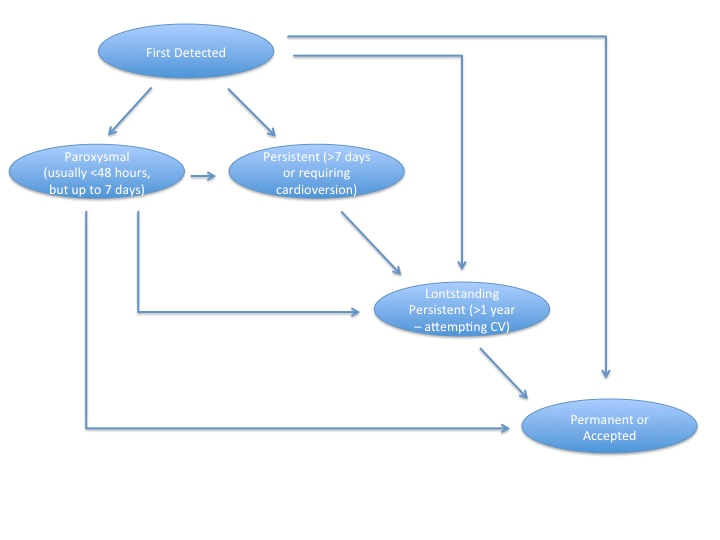

Mechanistically, atrial fibrillation is characterized by uncoordinated and uncontrolled activation of atrial tissue. Although numerous classification schemes exist, the most commonly employed classification system refers to timing and duration of the arrhythmia (Figure 1). Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation refers to episodes lasting usually less than 48 hours, although individual paroxysms may last up to 7 days. Persistent atrial fibrillation either lasts longer than 7 days or requires electrical/chemical cardioversion to restore sinus rhythm. Atrial fibrillation lasting greater than one year is either considered long-standing persistent if a rhythm control strategy is pursued or permanent if no further rhythm control methods are planned. ,

Figure 1

Classification of atrial fibrillation

Treatment and Prevention

Medical Therapies

Treatment strategies for atrial fibrillation center around two concepts: management of symptoms and prevention of complications. In terms of symptoms, management can either focus on rate or rhythm control. Rate control strategies include beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, digoxin, and in refractory cases, atrioventricular node ablation with pacemaker implantation. Rhythm control strategies include medical therapies such as sotalol, dofetilide, amiodarone, dronedarone, electrical cardioversion or pulmonary vein isolation.

Regardless of the treatment strategy for rate or rhythm control, treatment efforts must also focus on prevention of thromboembolic events. Atrial fibrillation increases the risk of cerebral ischemic events 5-fold across the entire spectrum of age, and it accounts for approximately 1.5% of events in patients under age 50 to greater than 20% of events in patients greater than age 80. Regardless of whether it is paroxysmal or permanent, the annual rate of cerebral ischemic events in patients with atrial fibrillation approaches 4.5% per year. In fact, even subclinical atrial fibrillation lasting 6 minutes or longer is associated with an increased risk of ischemic events.

Although the overall risk of cerebral ischemic events in patients with atrial fibrillation is understood on the population level, it is both practical and important to make attempts at individualizing the risk for a particular patient. A number of risk models have been proposed. The first is the CHADS2 score. In this model, a patient is assessed according to 5 established risk factors (Table 1) including age >75, history of hypertension, history of congestive heart failure, diabetes, and prior embolic event. Each risk factor is worth one point with the exception of a prior embolic event, which is worth two points. The resultant score ranges from 0-6 and corresponds to a significant increase in risk for each incremental score. The absolute risk varies by series. In one study of 1733 patients with atrial fibrillation not on warfarin, the annualized risk of cerebral ischemic events ranged from 1.9% for a CHADS2 score of 0 to 18.2% for a CHADS2 score of 6. In another, larger series of 11,526 patients with atrial fibrillation not on warfarin, the annualized risk of events ranged from 0.49% for a CHADS2 score of 0 to 6.9% for a CHADS2 score of 6. Although these two studies highlight variability in cerebral ischemic event risk across different populations, the unifying concept that higher CHADS2 scores portend higher event risk remains true.

Table 1. CHADS2 Score and Associated cerebral event Risk,

| CHADS2 Score | Annual Risk of Cerebral Events (± 95% CI) | Treatment Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.49% (0.30-0.78) 1.9% (1.2-3.0) |

Aspirin 325mg daily |

| 1 | 1.52% (1.19-1.94) 2.8% (2.0-3.8) |

Aspirin 325mg daily or Warfarin – target INR 2-3 |

| 2 | 2.50% (1.98-3.15) 4.0% (3.1-5.1) |

Warfarin – target INR 2-3 |

| 3 | 5.27% (4.15-6.70) 5.9% (4.6-7.3) |

Warfarin – target INR 2-3 |

| 4 | 6.02% (3.90-9.29) 8.5% (6.3-11.1) |

Warfarin – target INR 2-3 |

| 5 | 6.88% (3.42-13.84)* 12.5% (8.2-17.5) |

Warfarin – target INR 2-3 |

| 6 | 6.88% (3.42-13.84)* 18.2% (10.0-27.4) |

Warfarin – target INR 2-3 |

| Risk factors include: Age > 75 years old, Diabetes, Hypertension, Congestive Heart Failure (1 point each) and Prior thromboembolic event (2 points) for a total score of 0-6. *In this study, patients with CHADS2 scores of 5 and 6 were grouped together. |

||

Although the CHADS2 score is well studied and commonly applied, it is uncertain whether this score adequately stratifies low risk patients. This point is highlighted by the fact that even low risk patients (those with CHADS2 scores of 1) can benefit from oral anticoagulation with warfarin or the non-vitamin K oral anticoagulant medications discussed below. Furthermore, greater emphasis on certain risk factors and the addition of other known risk factors for cerebral ischemic events may further refine risk stratification. The CHA2DS2VASc score (Table 2) is a 9-point scale incorporating the factors in the CHADS2 system (congestive heart failure, hypertension, age >75, diabetes and prior stroke x2) placing increased emphasis on age (65-74 merits 1 point while ≥75 merits 2 points). Additionally, it adds vascular disease and female gender as risk factors. Based on an analysis of 1084 patients Lip et al., validated this risk model and demonstrated incremental risk of embolic events with a rising score (Table 2). This score has been further validated in a trial of over 7000 patients. While the CHA2DS2VASc score is a more comprehensive system, and it has become the standard in assessing thromboembolism risk, it is worth recognizing that small numbers at either end of the risk spectrum may under- or overestimate absolute risk.

Table 2. CHA2DS2VASc Score and associated cerebral event risk (n=1084).,

| CHA2DS2VASc Score | Annual Risk of Cerebral Event (±95% CI) | Treatment Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0% (0-0) | Aspirin alone or no therapy |

| 1 | 0.6% (0-3.4) | Aspirin (75-325mg) or oral anticoagulation |

| 2 | 1.6% (0.3-4.7) | Oral anticoagulation |

| 3 | 3.9% (1.7-7.6) | Oral anticoagulation |

| 4 | 1.9% (0.5-4.9) | Oral anticoagulation |

| 5 | 3.2% (0.7-9.0) | Oral anticoagulation |

| 6 | 3.6% (0.4-12.3) | Oral anticoagulation |

| 7 | 8.0% (1.0-26.0) | Oral anticoagulation |

| 8 | 11.3% (0.3-48.3) | Oral anticoagulation |

| 9 | 100% (2.5-100) | Oral anticoagulation |

| Risk factors include: Prior embolic event (2 points), Age > 75 (2 points), Age 65-74 (1 point), congestive heart failure (1 point), hypertension (1 point), diabetes (1 point), vascular disease (1 point), female gender (1 point). p=0.003 for trend. | ||

It is also important to balance the risk of cerebral ischemic events against the risk of bleeding. Numerous algorithms have been proposed, but the most commonly utilized is the HAS-BLED score (Table 3), incorporating hypertension, abnormal liver/kidney function, prior stroke, prior bleeding, labile INRs, elderly and drug/alcohol abuse on a 9 point scale. Scores of ≥ 3 are associated with increased bleeding risk, but it is important to note that often, similar factors (such as age and hypertension) increase both the bleeding risk and the risk of cerebral ischemic events, and often, the risk related to bleeding is outweighed by the risk of stroke. Decision algorithms designed to balance these risks have been proposed , and both the 2012 updated European guidelines and the 2014 ACC/AHA/HRS guidelines recommend thoughtful anticoagulation with close monitoring in patients at elevated risk for bleeding. ,

Table 3. HAS-BLED Score predicting bleeding risk.

| Table 3a – HAS-BLED | Table 3b – Annual Bleeding Risk | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Description | Points | Cumulative Points | Bleeding Risk |

| (H)ypertension | 1 | 1 | 1.02% |

| (A)bnormal liver function or renal function | 1 | 2 | 1.88% |

| 3 | 3.74% | ||

| (S)troke | 1 | 4 | 8.70% |

| (B)leeding | 1 | 5 | 12.50% |

| (L)abile INR | 1 | 6 | Insufficient Data |

| (E)ldery (Age > 65) | 1 | 7 | Insufficient Data |

| (D)rug use or alcohol use | 1 | 8 | Insufficient Data |

| 9 | Insufficient Data | ||

Multiple anticoagulation strategies to prevent cerebral ischemic events have been studied (Table 4), including aspirin, clopidogrel, warfarin and the direct oral anticoagulants: dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban and edoxaban. Both aspirin and warfarin have been compared to placebo. In 1999, Hart et al. published a meta-analysis of studies comparing aspirin to placebo, warfarin to placebo and aspirin to warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. Across the studies comparing aspirin to placebo with the primary endpoint of cerebrovascular accident, therapy with aspirin resulted in a relative risk reduction of 22% and an absolute risk reduction of 1.5% per year respectively for primary prevention and 2.5% per year for secondary prevention. In the studies comparing warfarin to placebo, warfarin resulted in a relative risk reduction of 62% with absolute reductions of 2.7% per year for primary prevention and 8.4% per year for secondary prevention. In 5 studies comparing aspirin to warfarin, warfarin resulted in a 34% relative risk reduction, proving superior to aspirin in the reduction of cerebral events; however, it should be noted that the risk of both intracranial and extracranial hemorrhage was higher with warfarin compared to aspirin.

Table 4. Anticoagulation options for patients with atrial fibrillation.

| Anticoagulation Strategy | Comparison Group | Study Name | Cerebral Events Risk | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin | Placebo | Hart et al. (Meta-analysis of 6 trials) | Relative Risk Reduction 22% (CI 2-38) | Superiority of aspirin over placebo |

| Warfarin | Placebo | Hart et al. (Meta-analysis of 6 trials) | Relative Risk Reduction 62% (CI 48-72) | Superiority of warfarin over placebo |

| Aspirin | Hart et al. (Meta-analysis of 5 trials) | Relative Risk Reduction 36% (CI 14-52%) | Superiority of warfarin over aspirin | |

| Dual Antiplatelet (Aspirin and clopidogrel) | Warfarin | Connolly et al. ACTIVE W | Relative Risk 1.44 (95% CI 1.18-1.76) | Trial stopped early due to benefit with warfarin |

| Aspirin | Connolly et al. ACTIVE A | Relative Risk 0.72 (95% CI 0.62-0.83) | Bleeding risk 1.57 (95% CI 1.29-1.92) | |

| Dabigatran 110mg twice daily | Warfarin | Connolly et al. RE-LY | Relative Risk 0.91 (95% CI 0.74-1.11) | Bleeding risk lower with dabigatran |

| Dabigatran 150mg twice daily | Warfarin | Connolly et al. RE-LY | Relative Risk 0.66 (95% CI 0.53-0.82) | Bleeding risk similar between groups |

| Rivaroxaban 20 mg daily | Warfarin | Patel et al. ROCKET-AF | Relative Risk 0.79 (95% CI 0.66-0.96) | Similar overall bleeding, less intracranial/fatal |

| Apixaban 5 mg twice daily | Warfarin | Granger et al. ARISTOTLE | Relative Risk 0.79 (95% CI 0.66-0.95) | Less overall bleeding and all-cause mortality |

| Edoxaban 30 mg daily | Warfarin | Guigliano et al. ENGAGE-AF | Relative risk 1.07 (95% CI 0.87-1.31) | Less bleeding and non CV death |

| Edoxaban 60 mg daily | Warfarin | Guigliano et al. ENGAGE-AF | Relative risk 0.79 (95% CI 0.63-0.99) | Less bleeding and non CV death |

Clopidogrel has also been studied in patients with atrial fibrillation. The Atrial Fibrillation Clopidogrel Trial with Irbesartan for Prevention of Vascular Events (ACTIVE) trials evaluated the efficacy and safety of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. The ACTIVE W trial evaluated dual antiplatelet therapy versus warfarin in 6726 patients with atrial fibrillation and at least one other risk factor for thromboembolic events with a primary endpoint of cerebral events, non-cerebral embolic events, myocardial infarction or vascular death. This study was stopped early, as therapy with dual antiplatelet therapy was associated with a significantly higher event rate (relative risk 1.44, 95% CI 1.18-1.76, p=0.003) compared to warfarin alone.

In the ACTIVE A trial, 7554 patients with atrial fibrillation at increased risk of stroke who were considered unsuitable candidates for warfarin therapy were randomized to aspirin plus clopidogrel versus aspirin alone. Over a mean of 3.6 years of follow-up, patients treated with dual antiplatelet therapy had a significantly lower risk of the composite primary endpoint consisting of cerebral event, non-cerebral embolic event, myocardial infarction or vascular death (relative risk 0.89, 95% CI 0.81-0.98, p=0.01) at the cost of an increased risk of bleeding (relative risk 1.57, 95% CI 1.29-1.92, p<0.01). As a result of these and other studies, dual antiplatelet therapy has not gained widespread acceptance for thromboembolic prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation except for patients in whom warfarin is contraindicated.

Although long-term anticoagulation with warfarin is efficacious, numerous drawbacks exist. The narrow therapeutic window of warfarin is a delicate balance between lack of efficacy and a significantly elevated risk of bleeding, therefore requiring frequent blood tests. Additionally, numerous food and drug interactions exist, thus making chronic management of multisystem disease difficult. Finally, in patients at risk for falling, anticoagulation itself may incur more risk than the thromboembolic event it is prescribed to prevent.

Highlighting these issues, warfarin therapy has been associated with bleeding rates upwards of 10% per year, leading to a regulatory “black box warning”. Additionally, up to 40% of patients with atrial fibrillation have contraindications to anticoagulation therapy. Warfarin is often underutilized or associated with difficulties in finding appropriate dosage.

Among patients who are at moderate or high risk for ischemic stroke and considered good candidates for warfarin therapy, it is prescribed in only 40% of patients, and even in the controlled Stroke Prevention Using an Oral Thrombin Inhibitor in Atrial Fibrillation (SPORTIF III and V) trial settings, up to 30% of patients were subtherapeutic and 15% supratherapeutic on warfarin. Finally, in a study of 41900 patients with chronic atrial fibrillation, only 50% of patients treated with aspirin and 70% of patients treated with warfarin remained on this therapy at one year, further highlighting difficulties with anticoagulation.

Despite these issues, vitamin K antagonists remain the most commonly employed medical thromboembolic prevention in atrial fibrillation, particularly in patients at elevated risk of thromboembolism. According to the ESC guidelines, assessing the individualized risk of cerebral events in patients with atrial fibrillation and the risks of chronic therapy with warfarin is paramount. , As outlined in Table 2, patients at low risk for cerebral events (CHA2DS2VASc score of 0) can be treated with aspirin alone or no therapy at all. Those at higher risk should be treated with oral anticoagulation unless otherwise contraindicated due to excessive bleeding risk. , ,

The non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants, dabigatran, rivaroxaban and apixaban have gained considerable interest for thromboembolic event prevention. The first such agent was dabigatran, studied in the Randomized Evaluation of Long-term Anticoagulation Therapy (RE-LY) Trial evaluating 18,113 patients with atrial fibrillation and an increased risk of stroke (mean CHADS2 score of 2). Patients were treated with warfarin or dabigatran (110 or 150 mg twice daily) with a primary endpoint of cerebral or systemic embolic events in a non-inferiority design. Both doses of dabigatran proved non-inferior to warfarin; however, dabigatran at 150 mg twice daily proved superior to warfarin with regard to both the primary endpoint (relative risk 0.66, 95% CI 0.53-0.82, p<0.001) as well as net clinical benefit, including the primary endpoint, bleeding and death (relative risk 0.91, 95% CI 0.82-1.00, p=0.04). This benefit appears to be even greater in patients with poor anticoagulation control with warfarin, but it should be noted that medication discontinuation rates were significantly higher with either dose of dabigatran than with warfarin at both one year (14.5% dabigatran 110 mg, 15.5%, dabigatran 150 mg, 10.2% warfarin, p<0.01) and two-years (20.7% dabigatran 110 mg, 21.2%, dabigatran 150 mg, 16.6% warfarin, 0<0.01).

Rivaroxaban was studied in the 14,226 patient Rivaroxaban Once Daily Oral Direct Factor Xa Inhibition Compared with Vitamin K Antagonism for the Prevention of Stroke and Embolism Trial in Atrial Fibrillation (ROCKET AF). Patients were randomized to either warfarin targeted to an INR of 2.0-3.0 or rivaroxaban 20 mg daily (15 mg daily for creatinine clearance 30-49 ml/min) with a primary composite endpoint of stroke and systemic embolism. In the primary, as-treated analysis, there were similar rates of stroke and systemic embolism (1.7%/year rivaroxaban vs. 2.2%/year warfarin, HR 0.79, 95% CI 0.66-0.96, p<0.001 for non-inferiority). There were similar rates of bleeding between the two groups, but intracranial (0.5% vs. 0.7%, p=0.02) and fatal bleeding (0.2% vs. 0.5%, p=0.0.03) were both significantly lower in the rivaroxaban treated patients.

The Apixaban for Reduction of Stroke and Other Thromboembolic Events in Atrial Fibrillation (ARISTOTLE) trial randomized 18,201 patients with atrial fibrillation and at least one risk factor for cerebral embolic events to warfarin with a goal INR of 2.0-3.0 or apixaban 5 mg twice daily with a primary endpoint of stroke or ischemic embolism over a median 1.8 year follow-up. In this study, the primary endpoint occurred in 1.27%/yr. in the apixaban group compared to 1.6%/year in the warfarin group (HR 0.79, 95% CI 0.66-0.95, p<0.001 for non-inferiority, p=0.01 for superiority). Apixaban was also associated with reductions in major bleeding (2.1%/year apixaban vs. 3.1 %/year warfarin, p<0.001) and all-cause mortality (3.5% apixaban vs. 3.9% warfarin, p=0.047).

The Effective Anticoagulation with Factor Xa Next Generation in Atrial Fibrillation–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 48 (ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48) randomized 21,105 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation to warfarin (n=7036) or edoxaban at either 60 mg (n=7035) or 30 mg (n=7034) with a primary efficacy endpoint of stroke or systemic embolic event and a primary safety endpoint of major bleeding. In this noninferiority designed trial, stroke or systemic embolism occurred in 1.50% patients/year with warfarin versus 1.18% patients/year with edoxaban 60 mg (HR 0.79; 97.5% CI 0.63-0.99; p<0.001 for noninferiority) and 1.61% patients/year with edoxaban 30 mg (HR1.07; 97.5% CI, 0.87-1.31; p=0.005 for noninferiority).

Bleeding events occurred at a rate of 3.43% patients/year with warfarin versus 2.75% patients/year with edoxaban 60 mg (HR 0.80; 95% CI, 0.71 to 0.91; p<0.001) and 1.61% patients/year with Edoxaban 30 mg (HR 0.47; 95% CI, 0.41 to 0.55; P<0.01). Additionally, non-cardiovascular death, a prespecified secondary endpoint, occurred in 3.17% patients/year with warfarin versus 2.74% with edoxaban 60 mg (HR 0.86; 95% CI, 0.77 to 0.97; p=0.01), and 2.71% with edoxaban 30 mg (HR 0.85; 95% CI, 0.76 to 0.96; p=0.008).

While target specific oral anticoagulants appear to be both safe and effective for patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation, it is important to note that the clinical trials involve carefully selected patients, and these agents will require post-market analysis to establish their relative utility in more general populations. Additionally, the pivotal trials were conducted against warfarin, so head-to-head comparisons are accordingly lacking. Nevertheless, the preponderance of evidence suggests that oral anticoagulation is superior to antiplatelet therapy alone, and these newer agents have advantages over warfarin in appropriately selected patients.

The Origins and Evolution of LAAO

In 1946, William Dock applied the thought of removing thrombus together with its site of origin to prevent recurrent systemic emboli to the specific patient population with rheumatic heart disease, mitral stenosis, atrial fibrillation, and recurrent arterial emboli. He proposed left atrial appendage resection as a solution. In 1949, John L. Madden successfully performed left atrial appendage resection on two patients with rheumatic heart disease, mitral stenosis, and atrial fibrillation with peripheral arterial and aortic emboli, respectively. He observed that in over 90 percent of cases of rheumatic heart disease, the thrombi were found in the left atrium, particularly the appendage. This preliminary observation would be observed decades later in a meta-analysis conducted by Blackshear and Odell. They noted in their review that 201 of 222 (91%) of nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation-related left atrial thrombi originated in the left atrial appendage. In comparison, 254 out of 446 (57%) of patients with rheumatic atrial fibrillation had thrombi originating from the left atrial appendage. This observation had profound lasting clinical implications, as LAAO is performed in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. With this knowledge, surgical excision of the left atrial appendage occurred with concomitant cardiac surgery such as mitral valve replacement and repair and coronary artery bypass graft surgery, though appendage obliteration was not standard fare for every cardiac surgery case and highly dependent on surgeon preference. The maze procedure developed by Cox for atrial fibrillation entails multiple planned incisions in the right and left atria and complete right and left atrial appendage excision with suture closure. The Percutaneous Left Atrial Appendage Transcatheter Occlusion (PLAATO) device was the first transcatheter endovascular device developed in 2000, which fueled many studies and investigations, ultimately culminating in the approval and widespread application of percutaneous left atrial appendage occlusion.

Left Atrial Appendage Anatomy

The LAA is an embryonic remnant of the primordial left atrium, with a varied range of several architectural facets including ostial diameter, depth, and shape. This structure stretches across the anterior and lateral walls of the left atrium, nestled in the atrioventricular groove inferior to the pulmonary outflow trunk and superior to the left ventricle. The LAA tip is directed anterosuperiorly and rests along the left border of the right ventricular outflow tract. The LAA is a thin-walled structure (1 mm) lined with thick (> 1 mm) trabeculated pectinate muscles, and distinguishes itself embryologically from the rest of the smooth-walled left atrium. The ostia of the LAA have a number of described shapes and diameters, including oval (82%), triangular (7%), semi-circular (4%), and round and water-drop shapes. The body of the LAA has been characterized by CT and MRI and divided into four different morphological categories: chicken wing, cactus, windsock, and cauliflower. The chicken-wing morphology has been shown to be associated with a 79% reduced chance of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation (after adjusting for CHADS2 score, gender, and type of AF), while the cactus, windsock and cauliflower morphologies is associated with a four-to-eight-fold greater risk of stroke. Patients with persistent AF are more likely to have non-chicken wing LAA morphologies compared with patients with paroxysmal AF. The normal LAA exhibits wide variations in the number of lobes, length, and volume. In an autopsy study of 500 normal hearts, Veinot et al., found that 54% of LAA had two lobes, whereas 23% had 3 lobes and 20% had only one lobe. Volumes ranged from 0.7-19.2 cc, length ranged from 16-51 mm and orifice diameter ranged from 10-40 mm. Patients with persistent AF have been shown to have a higher LAA volume and larger and rounder ostial area, so the duration of AF should be considered whenever embarking on device-sizing selection. The normal LAA exhibits contractility and quadriphasic blood flow; both properties are impaired in patients with atrial fibrillation.

Surgical LAA exclusion

Surgical exclusion of the LAA is the earliest form of LAAO, dating back to the 1940s. Surgical exclusion of the LAAO had been increasingly common when patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing otherwise indicated cardiac surgery despite little published data to support the efficacy of this practice. The first randomized trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of surgical LAAO was the Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion Study (LAAOS) published in 2005. In this trial, 77 patients with atrial fibrillation and risk factors for cerebral events undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery were randomized 2:1 to LAA exclusion (LAAE) (with sutures or staples) or no treatment. LAAE did not prolong bypass time or increase heart failure, atrial fibrillation, or bleeding incidences. There were 9 LAA tears easily repaired by suture. Of the 52 patients randomized to exclusion, 44 underwent repeat TEE.

There was such a low success rate with LAA closure with sutures (5 out of 11 patients, 45%) that the study converted to using staplers for closure. There was a trend towards more success with staples, with 24/33 (72%) of patients achieving complete closure, though because staples were used later in the study when surgeons were gaining more experience with the procedure, it is hard to dissect which factor contributed more towards success. Interestingly, no statistical significance for occlusion success was detected between the suture and staple groups (p = 0.14). The study was not powered to assess events, but the results suggest suboptimal closure rates despite the employment of multiple techniques. With regards to stroke, 2 patients (2.6%) had periprocedural stroke (one had an ischemic stroke intraoperatively, the other had a transient ischemic attack (TIA) on postoperative day 3), though this study was not powered to determine stroke outcomes. Patients were followed for 13 ± 7 months, and no patient had any stroke in the long-term. The authors conclude that use of a staple device by an experienced surgeon creates a successful (>90%) platform for surgical LAAE. Over a decade ago, meta-analyses investigating the benefit of surgical LAAE yielded conflicting results (this included the LAAOS study) and overall were unable to support the practice, citing incomplete closure (average 55-65%) as the primary driver behind the disappointing results. As a result, surgical LAAE during cardiac surgery for patients with AF was listed as a class IIb recommendation, though this does not deter performance of the procedure in clinical practice.

A more recent effort by Atti et al., to derive a meta-analysis of 12 studies of patients undergoing surgical LAAE versus not during concomitant cardiac surgery (valve and coronary artery bypass grafting surgeries were included) showed that patients with exclusion had lower events of systemic embolism (p < 0.001) and stroke (p < 0.0001). Successful exclusion is heavily influenced by operator experience, technique, and anatomy; this analysis was also unable to decipher which surgical technique yielded best results. In contrast to percutaneous LAAO, questions regarding long-term anticoagulation after surgical exclusion have not yet been answered. The updated 2020 ESC/EACTS guidelines recommend enduring anticoagulation therapy in patients with AF surgery and appendage closure, depending on their CHA2DS2 -VASc score and overall stroke risk (Class I, level of evidence C).

Further bolstering the utility of LAAE during cardiac surgery for patients with AF, more recently in 2021, the Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion during Cardiac Surgery to Prevent Stroke (LAAOS III) Study was published. This is a randomized, multicenter trial involving patients with atrial fibrillation (CHA2DS2 -VASc ≥2), in which patients were randomly assigned to undergo left atrial appendage occlusion during cardiac surgery scheduled for another indication. Surgical LAAE methods included the standard and preferred amputation and closure, stapler closure, TEE-confirmed double-layer linear closure, or closure with an approved surgical occlusion device. Patients were expected to adhere to oral anticoagulation post-surgery. The primary outcome assessed was occurrence of stroke or systemic embolism. At 3 years, 77% of the participants continued to receive oral anticoagulation. Stroke or systemic embolism occurred in 114 out of 2379 (4.8%) patients in the occlusion group and in 168 out of 2391 (7.0%) in the no-occlusion group (hazard ratio 0.67, P = 0.001), with an estimated number needed to treat to prevent one stroke over 5 years of 37 (95% CI, 22 to 111). Surgical occlusion had little effect on bypass time and cross-clamp time and did not have a significant effect on the secondary outcomes of death, hospitalization for heart failure, myocardial infarction, or bleeding. LAAOS III suggests that the anti-embolic effects of surgical LAAO are additive to those of oral anticoagulation. The study did not compare surgical LAAO alone against anticoagulation, so surgical LAAO alone cannot be considered a replacement for anticoagulation at this time. The LAAOS III study was not designed to parse out which surgical method of closure may be superior, or whether surgical occlusion was sustained over the long-term. Because surgical exclusion is an extravascular procedure (as compared to endovascular percutaneous occlusion devices), there is speculation this may protect against device-related thrombus and future strokes, although this has never been studied.

Surgical occlusion devices have been studied and are promising alternatives to amputation, sutures, and staples because of the fragility and bleeding of the LAA and the risks that are attendant with incomplete closure. The AtriClip Gillinov-Cosgrove Left Atrial Appendage Exclusion system (Atricure Inc, Westchester, Ohio), or simply known as the AtriClip, was FDA approved in 2010 after results of The Exclusion of Left Atrial Appendage with AtriClip Exclusion Device in Patients Undergoing Concomitant Cardiac Surgery (EXCLUDE). The Atriclip is a clip with 2 stiff, parallel titanium tubes covered with knit-braided polyester sheaths and connected by elastic nitinol springs, delivering uniform pressure over the length of the tubes once the device is deployed epicardially. The AtriClip comes in 4 different custom-fitted sizes (35 mm, 40 mm, 45 mm and 50 mm). EXCLUDE was a nonrandomized, prospective, multicenter designed to assess the safety and efficacy of AtriClip in patients with AF undergoing elective cardiac surgery via median sternotomy. Safety was measured by device-related adverse events at 30 days. Efficacy was determined by verification of flow cessation to the LAA as measured by a combination of intraprocedural TEE and 3-month CTA. There were no damage or tears to the LAA or surrounding anatomy, device migration, or bleeding or repair sutures required in any of the patients. At 1 year, 2 patients had strokes thought to be hypertensive and atherosclerotic in etiology (unrelated to device). Of the 70 patients who underwent successful AtriClip device placement, 67 of those (95.7%) achieved successful exclusion by intraprocedural determination, and of the 61 patients who had follow-up TEE or CT, 60 (98.4%) had complete exclusion.

A corresponding European safety and feasibility study with 34 patients showed successful clip placement with no device-related complications, no stroke, and documented stable clip placement on CT at 3 months, leading to CE mark approval. The AtriClip was further tested in the ATLAS trial, a prospective, randomized, multicenter, unblinded trial comparing patients without documented AF and an elevated CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED score in a 2:1 manner into those who received LAAE and those who did not during otherwise scheduled cardiac surgery. Efficacy endpoints were: 1) incidence of perioperative events such as stroke, bleeding, myocardial infarction, and death, 2) successful intraoperative LAAE, and 3) composite stroke rates through 365 days in those patients who developed postoperative AF (POAF). The clip was successfully placed in 373 patients, with no peri-procedural sequelae. POAF occurred in 47% of the LAAE group and in 38% of the no LAAE group (p = 0.047). While there was a higher incidence of POAF in the LAAE arm, there was a trend towards lower stroke rate in the LAAE arm, with a 1.1% versus 2.8% perioperative stroke rate and a 3.4% versus 7.0% total thromboembolic rate at 1 year in the LAAE versus no LAAE arm, respectively. Overall, clip placement was procedurally successful 99% of the time, with low adverse events rates (0.3%). POAF development was higher in the LAAE group, without a higher ischemic stroke rate. There was no difference in mortality between the 2 groups at 30 days and 1 year.

Cumulatively, it appears the AtriClip is a safe and effective modality for LAAE. An additional noted benefit of the AtriClip is that it provides acute electrical isolation of the LAA, combining both stroke prevention effects and reduction in incidence of recurrent AF. Set to be completed in 2032, AtriCure has an ongoing superiority trial called the The Left Atrial Appendage Exclusion for Prophylactic Stroke Reduction Trial (LeAAPS), which is an expansion to ATLAS in that it will assess the ability of LAAE (versus no LAAE) to prevent ischemic stroke or systemic embolism in patients without AF who are undergoing cardiac surgery.

Overall, as it stands in the 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation, surgical exclusion of the LAA can be considered in patients with AF already undergoing cardiac surgery, as determined by the patient’s heart team (Class IIb, Level of Evidence B- non-randomized, upgraded from C).

Percutaneous LAA occlusion

The primary downside of surgical LAA occlusion is that it holds minimal appeal as a stand-alone procedure. The trials investigating its utility included only patients undergoing cardiac surgery for another indication. Percutaneous means to occlude the LAA are intuitively attractive as they may be equally (or more) effective with substantially less physiologic insult to the patient and an overall improved safety profile compared to surgical closure or even medical therapy. A number of devices have thus far been developed for occlusion of the left atrial appendage. Initial devices included the Percutaneous Left Atrial Appendage Occluder (PLAATO, eV3, Inc., Plymouth, MA, USA) and the Watchman Left Atrial Appendage System (Boston Scientific Corporation, Marlborough MA, USA). Additionally, Amplatzer ASD and VSD devices (St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, MN, USA), although originally not intended to occlude the left atrial appendage, have been utilized to occlude the LAA. The Amplatzer Amulet left atrial appendage occluder is an iterative design of the ACP, specifically developed for atrial appendage occlusion, and it has recently become available in a number of countries. Additionally, the WaveCrest (Coherex Medical, Salt Lake City, UT, USA), Ultraseal (Cardia Inc, Eagan, MN, USA) and LAmbre (LifeTech Shenzhen, China) devices are three newer devices with CE mark approval. Finally, the Lariat device (SentreHEART, Redwood City, CA) provides an extracardiac means to ligate/occlude the left atrial appendage.

Transcatheter Anatomical Considerations

The interatrial septum is important to examine for the presence of patent foramen ovale (PFO), thickened septum, atrial septal aneurysm, or prior patch repair. The presence of these can help to determine the feasibility of device closure along with the selection of type and size of the LAA closure device. Trials involving LAAO device placement generally exclude patients with congenital heart disease such as atrial septal defect or septal aneurysms.

Knowledge of the LAA’s diameter and depth is key when selecting the dimensions of the device. One of two core device-sizing selection principles to strive for is device-diameter matching and adequate device compression, defined as achieving 8-20% of device compression by the LAA ostium. This is accomplished by choosing the largest device as allowed by the LAA depth that simultaneously reaches ideal compression, without oversizing the device (not exceeding device compression of greater than 30-35% of the maximal ostial diameter). The spectrum of existing ostial shapes should be accounted for when measuring maximal ostial diameter. Available devices are generally round whereas most ostia are oval; thus, device selection to maximal diameter aims to prevent incomplete sealing and peri-device leak. The second principle in device-sizing selection is to measure LAA depth, defined as the midpoint of the diameter line of the maximal ostial orifice to the most distal point in the LAA, usually at the apex of the most anteriorly-directed lobe. If there is an instance where the maximal depth of the LAA is shallower than the shortest device that is wide enough to allow good compression, then that device may not be used. As the LAA consists of relatively thin, friable tissue, overly deep device placement may lead to LAA rupture, hemopericardium, and tamponade. Failure to circumnavigate the given LAA anatomy can lead to the need for intraprocedural resizing, potential complications, and longer procedure times.

Preprocedural Imaging

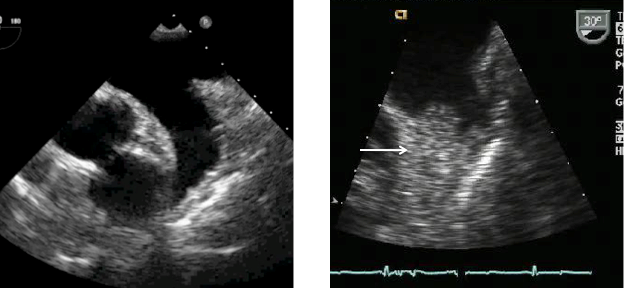

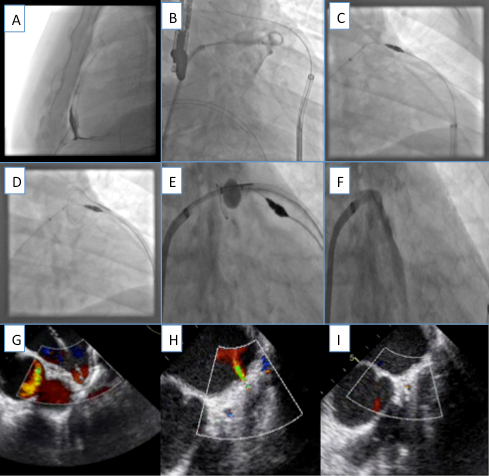

Intraprocedural transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) and fluoroscopy remain the established standard imaging modalities for assessment of anatomic variation, device positioning, assessment of successful deployment, and monitoring of complications during percutaneous transcatheter LAAO device delivery (Figure 2 and Figure 8). Preprocedural imaging with three-dimensional computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan can be useful for device sizing selection and characterization of complex LAA anatomy. In fact, CT has been shown to be superior to TEE for LAA morphology characterization, accurate device sizing, and evaluation of surrounding extracardiac structures and comparable to TEE for evaluation of thrombus. In the single-center, Prospective, Randomized Comparison of Three-Dimensional CT Guidance Versus TEE Data for LAA Occlusion (PRO3DLAAO) trial, CT-guided LAAO case planning was associated with greater accuracy in device selection on the first attempt (92% versus 27% with 2D-TEE; p = 0.01), although with the allowance of intra-procedural upsizing in the 2D-TEE cohort, the 2D-TEE cohort accuracy increased to 64% (P = 0.33). This study found significantly increased efficiency during the LAA procedure with CT versus 2D-TEE; less devices and guide catheters were used and procedure time was reduced.

Figure 2

LAA appendage

Left: Transesophageal echocardiographic image of a normal left atrial appendage.

Right: Left atrial appendage with significant thrombus (arrow)

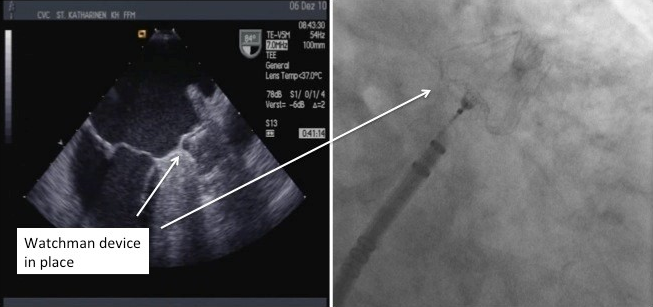

Figure 8

Fluoroscopic and Echocardiographic view of deployed Watchman device.

Transseptal Puncture (TSP) Technique

TSP was first utilized in 1959 for hemodynamic measurement of LA pressure with a chief goal of crossing the interatrial septum (IAS) mainly via the fossa ovalis (FO). Since the advent of structural and electrophysiologic interventions, TSP has been used with more attention to site-specific access. The ideal TSP site for LAAO differs in comparison with other structural interventional device TSP sites, depending on the anatomic needs of the landing zone for the device. When performing LAAO, it is important to remember the length of the LAA is directed anteriorly, and the central axis of the LAA ostium lies perpendicular to the body of the LAA. Landing the LAAO device successfully in the ostium depends on positioning the delivery sheath with enough depth within the LAA. With the anterior orientation of the LAA, a posterior-anterior trajectory of the sheath is most suitable for maneuverability within the LAA. Starting from a posterior TSP provides the most favorable sheath orientation and flexibility for directing the sheath anteriorly. Starting from a position that is too superior or anterior will complicate sheath alignment through the ostium into the long axis of the LAA. Additionally, a posterior position avoids inadvertent puncture of the aorta. Of note, different LAAO devices require slight modifications in TSP height, depending on the shapes and trajectories of the delivery sheaths. For example, the Watchman and Amplatzer Cardiac Plug are best delivered from a mid-septal to slightly inferior TSP, whereas the LARIAT device is better delivered slightly more superiorly.

Traditionally, TEE guides intraprocedural TSP. The bicaval view (100 to 120 degrees) is the primary working view, which displays the superior-inferior axis of the atrial septum. Biplane mode on TEE allows simultaneous visualization of the secondary working view, the orthogonal short-axis view (10 to 30 degrees), which displays the anterior-posterior axis of the atrial septum. For purposes of orientation, the bicaval view shows the superior-inferior axis with superior to the right (toward the SVC) and inferior to the left (away from the SVC); the short-axis view shows the anterior-posterior dimension with anterior to the right (toward the aortic valve [AV]) and posterior to the left (away from the AV). Clockwise rotations move the apparatus more posteriorly, whereas counterclockwise rotations move the apparatus more anteriorly. Intracardiac echocardiography (ICE) is an alternative to TEE for intraprocedural TSP guidance and it has several advantages that may make it preferable for some operators. Procedures may be more efficient as the primary operator can manipulate the ICE probe instead of depending on anesthesia for TEE guidance and reduce the necessity of intubation. The small caliber of the catheter (8- to 10-F) minimizes the cluttered appearance on fluoroscopic views. However, ICE requires additional vascular access.

Crossing the IAS for TSP is best achieved under echocardiographic visualization. There are numerous devices for crossing, employing needle, wire or radiofrequency to aid in successful puncture. Upon crossing the septum, heparin is given for a goal activated clotting time of 250 seconds, and the dilator is advanced. If this encounters resistance, the atriotomy site can be modified with coronary balloon dilatation or balloon-assisted crossing. Sheath-uncrossable cases should be managed similarly via additional dilation of the IAS.

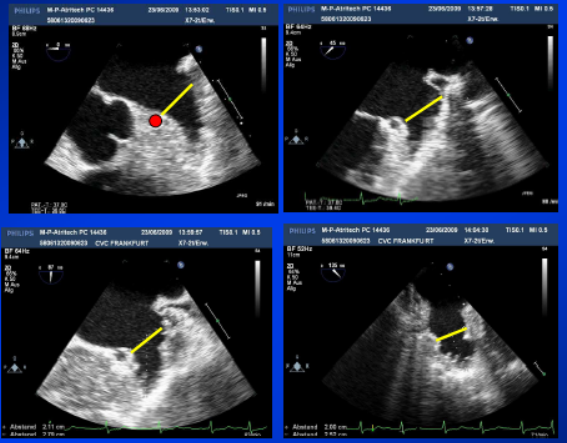

Once transseptal access is completed, a sheath is placed across the septum and a pigtail catheter is inserted into the LAA. This technique minimizes trauma to the LAA on engagement. Multiple fluoroscopic and echocardiographic measurements are made to accurately define the diameter, angle and depth and specific anatomy of the atrial appendage (Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5). After the appropriate size is determined, the device is positioned in the LAA, and the delivery sheath is retracted, thus deploying the device. Upon determination of successful deployment, the delivery sheath is detached from the device. At this point, the sheath is withdrawn into the right atrium. Details pertaining to each individual device are discussed below.

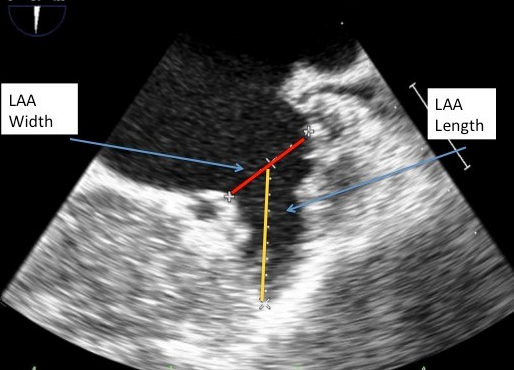

Figure 3

Echocardiographic measurements of the Left Atrial Appendage

Echocardiographic measurements of the left atrial appendage. Multiple views are taken to optimally visualize the LAA landing zone width.

Figure 4

Echocardiographic measurements of the LAA length and width.

Echocardiographic measurements of LAA length (yellow) and width (red) taken in 45 degree view of the LAA.

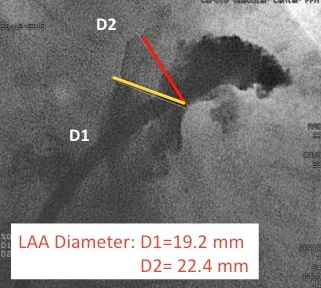

Figure 5

Angiographic measurments of the LAA.

Angiographic measurements (RAO caudal) of the LAA.

Combined Percutaneous Procedures

As in the surgical sphere, where LAAE is being done simultaneously with other planned cardiac procedures due to safety and convenience, there is also an increase in popularity of tandem LAAO and other procedures, such as AF ablation. Between 2016 and 2019, there was a 60% increase in combined AF ablation and LAAO procedures. When compared with standalone matched LAAO or AF ablation procedures, there was no significant difference in major adverse cardiac events (MACE) or 30-day readmission rates with combined AF ablation and LAAO procedures. The WATCH-TAVR trial is currently underway to compare all-cause mortality, stroke, and bleeding rates in patients with AF who are undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) and LAAO with those undergoing TAVR alone.

Percutaneous Devices

PLAATO

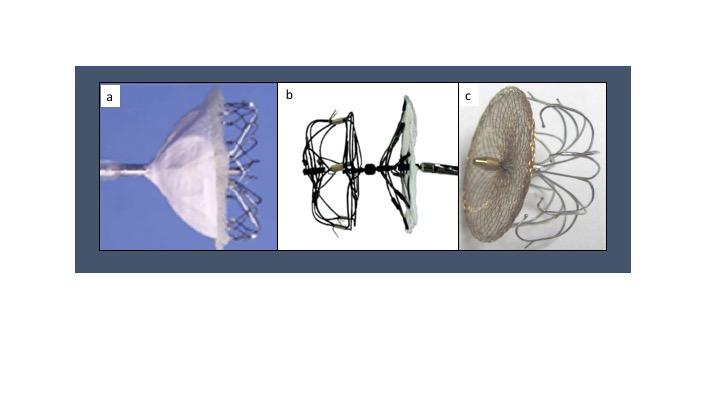

The Percutaneous Left Atrial Appendage Transcatheter Occlusion (PLAATO) device (Figure 6) was the first patented LAA occlusion device, designed by Dr. Michael Lesh and sponsored by the company Appriva. Dr. Horst Sievert was the first to successfully implant the PLAATO device in humans in 2001. LAAO devices were developed in the peak era of coronary stent development, so design concepts such as self-expansion carry over. The device consisted of a self-expandable balloon-shaped nitinol cage 15 to 32 mm in diameter and was coated with expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE). A membrane covered the atrial surface of the device, and the device anchored into the LAA ostium using three rows of projecting anchors. In 2005, Ostermayer et al., reported the results of a nonrandomized international multicenter prospective feasibility trial in 111 patients with non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation of at least 3 months duration who had contraindications to therapy with warfarin. The PLAATO system was successfully implanted in 97.3% of patients (108/111). Post-procedural antiplatelet therapy consisted of acetylic acid and clopidogrel. Four patients developed pericardial effusions or cardiac tamponade, and pericardiocentesis was necessary in three of them. One patient experienced a hemothorax and another a pleural effusion. At 6 months follow-up, successful LAA occlusion was demonstrated in 98% of the patients with a transesophageal echocardiogram. One patient developed a laminar thrombus on the device, detected at routine 6-month follow-up. During a follow-up period of 91 patient-years, two patients had a stroke, leading to an annual stroke rate of 2.2% after successful left atrial appendage occlusion. This represents a 65% relative risk reduction compared to a CHADS2 score predicted stroke rate of 6.3% in this patient cohort. Extending results out to 5-years, Block et al., reported on 64 patients entered into the North American cohort of this study. Over 239 patient years of follow-up, the annualized cerebral events rate in this population (mean CHADS2 score of 2.6) was 3.8% while the expected rate was 6.6%. While the results demonstrated feasibility and acceptable risk profiles, there were criticisms. LAAO devices are designed to prevent adverse events such as stroke, so any causative embolic or adverse event from device placement represents a prohibitive liability. The need and duration for antiplatelet therapy was not systematically addressed. Although the authors desired larger studies to expound on these questions, the company was unable to design and fund randomized controlled trials that would navigate the device to regulatory approval, and so this foundational prototype was discontinued from production and sale.

Figure 6

PLAATO device (EV3, Plymouth, MA, USA)

Watchman

Following successful implantation of the PLAATO device in 2001, the first Watchman device (Atritec Inc, Plymouth, MN) was implanted in 2002. The Watchman was developed by interventional cardiologists in conjunction with engineers at Atritec Inc, a medical startup company. The most important differentiating factor from a design standpoint for the Watchman, in contrast to the PLAATO device, was its open-end distal design as well as a semipermeable fabric covering rather than a closed-end design with PTFE covering (Figure 7). This design strategy proved able to accommodate a larger range of anatomies and heal within the endocardium more completely and quickly. An important early hurdle for the device was thrombus formation on the polymer covering observed in the early days after implantation, which was ameliorated in preclinical studies by adding warfarin therapy for 6 weeks post-implantation to allow time for device seal within the endocardium. The company worked with the FDA early on in its nascent clinical experience phase, building a portfolio of clinical studies which subsequently led to two successful randomized clinical trials (PROTECT AF and PREVAIL).

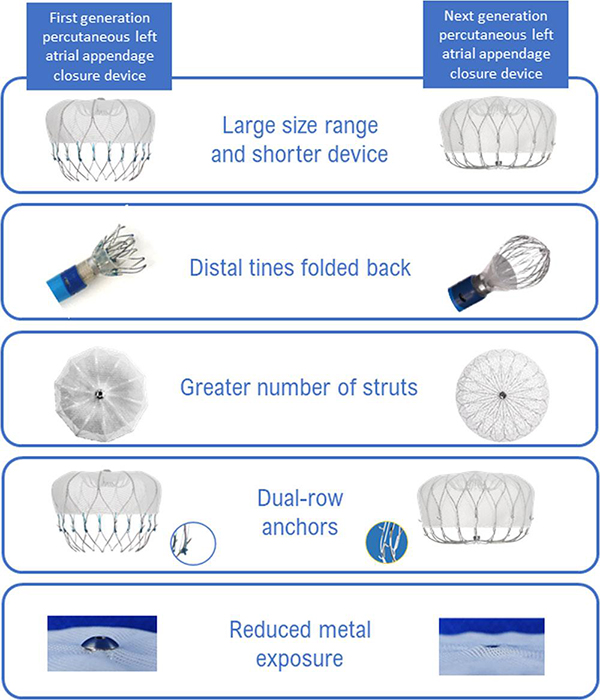

Figure 7

Watchman versus Watchman FLX devices.

Watchman FLX (Boston Scientific, Minneapolis, MN, USA) Reprinted with permission from Kar S, Doshi S, Sadhu D, et al. Primary Outcome Evaluation of a Next-Generation Left Atrial Appendage Closure Device. Circulation. 2021;143:1754–1762. DOI:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.050117

In a formative 2007 safety and feasibility study of the early Watchman device, Sick et al., reported the initial experience of 75 patients. The device was successfully implanted in 66/75 (88%) of patients with 93% complete sealing of the LAA at 45 days. Device embolization occurred in two of the initial 16 patients with successful retrieval. This led to redesign of the fixation barbs with no further embolic instances with suggestion of improvement in stroke risk. Additional adverse events included cardiac tamponade in two patients, air embolism in one patient, and delivery wire fracture requiring surgery in one patient. Four patients developed a flat layer of thrombus on the device at 6 months, and these resolved with additional anticoagulation. Two patients experienced a transient ischemic attack (mean CHADS2 score of the 66 patients was 1.8 ± 1.1). (36) Fifty-five of 60 patients (91.7%) seen at 6-month follow-up had discontinued warfarin therapy. There were no cerebral events during a mean follow-up of 24 months.

In the 2009 PROTECT AF (Percutaneous closure of the left atrial appendage versus warfarin therapy for prevention of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: a randomised non-inferiority) trial, 707 patients with atrial fibrillation and a CHADS2 score of ≥ 1 were randomized to LAA occlusion with the Watchman device and planned discontinuation of warfarin after 45 days versus continued therapy with warfarin. Randomization was 2:1 favoring LAA occlusion. The study had a non-inferiority design with a composite primary efficacy endpoint of cerebral and systemic embolic events, and cardiovascular death. The primary safety endpoint was a composite of hemorrhagic events, pericardial effusion and device embolization. The device was successfully implanted in 88% (408/463) of patients, and at 45 days 86% of these patients were able to discontinue warfarin. Safety events were higher in the intervention group and peri-procedurally correlated. There was a higher rate of ischemic events in the intervention group, mainly linked to periprocedural air emboli. Three of five patients with ischemic stroke had no long-term deficits, whereas the remaining two were discharged to nursing homes and subsequently died. There was a 4.8% event rate of non-disabling, non-fatal pericardial effusions requiring drainage versus no events in the warfarin group. Events in the warfarin group occurred at any point along the timeline of duration of treatment. Hemorrhagic strokes were more frequent in the warfarin group. Five of six hemorrhagic strokes in the warfarin group were fatal. There was one fatal hemorrhagic stroke in the intervention group during the 45-day period on warfarin. Numerically, the rate of all strokes was lower in the intervention group but this did not reach statistical significance for superiority.

Cumulatively, mortality rates were 3.0% for the intervention group (95% CI 1.3–4.6) versus 3.1% for the control group (95% CI 0.8–5.4) at 1 year, and 5.9% (95% CI 2.8–8.9) versus 9.1% (95% CI 4.2–14.1) at 2 years.

The results of this trial have since been extended out to 2.3 years with a favorable impact on quality of life. Continued efficacy of the Watchman device was demonstrated at 4-year follow-up. In the 463 Watchman-treated patients compared to the 244 medically-treated patients, the primary endpoint was noninferior (2.3% vs. 3.8%, relative risk 0.60, 95% CI 0.41-1.05). Interestingly, at last follow-up all-cause mortality (3.2% vs. 4.8%, relative risk 0.66, 95% CI 0.45-0.98, p = 0.0379) and cardiovascular mortality (1.0% vs. 2.4%; relative risk 0.40, 95% CI 0.23-0.82, p= 0.0045) were lower in Watchman treated patients.

In view of lingering concerns from the United States Food and Drug Administration regarding the safety of the device after the results of the PROTECT AF trial, the 2014 Prospective Randomized Evaluation of the Watchman LAA Closure Device In Patients With Atrial Fibrillation Versus Long Term Warfarin Therapy (PREVAIL) trial was designed to further explore the safety and efficacy of the device compared with standard-of-care warfarin. In the trial, 407 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and a mean CHADS2 score of 2.6±1.0 (a higher-risk group than in PROTECT AF) were randomized to either LAA occlusion with the Watchman device (n=269) or medical therapy (n=138) with a primary combined endpoint of stroke, systemic embolism and cardiac/unexplained death. At 18-months, the primary endpoint rate was 0.064 in the device group versus 0.063 in the control group (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.89), and this did not meet the prespecified margin to satisfy noninferiority. The control group had unexpectedly low rates of events as compared to event rates found in other contemporary trials utilizing warfarin as stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation i.e., RELY and ARISTOTLE. The second noninferiority endpoint of stroke and system embolism >7 days post randomization was satisfied. On balance, this trial was limited by extremely low event rates in both groups, and the rates of pericardial effusion requiring surgical repair decreased in this trial to 0.4% (compared to 1.6% in PROTECT AF). Strokes caused by the procedure or related to the device decreased in PREVAIL (0.4%) as compared with PROTECT AF (1.1%, p = 0.007) These findings led to the general conclusion that LAA occlusion is both safe and effective.

While the Watchman had already secured Conformité Européenne (CE)-mark approval in 2005, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration only approved the Watchman device in 2015 after the PREVAIL and PROTECT AF results, to be used for patients at increased risk of stroke from non-valvular atrial fibrillation who qualify for warfarin but have a reason for pursuing mechanical anti-embolic methods after patient-physician discussion. Prior to this governmental imprimatur of the Watchman, the Continued Access to PROTECT AF (CAP) and the CAP2 Registries were established to provide long-term data on the safety and efficacy of the device. The CAP registry was nonrandomized and included 460 patients from 26 centers and included the same criteria and procedural protocol as described in PROTECT AF. In combination with data from PROTECT AF, the rates of serious pericardial effusion and strokes decreased between PROTECT AF and CAP. Effusion rates fell from 27 of 542 (5.0%) in PROTECT AF to 10 of 460 in CAP (2.2%; P=0.019), and stroke rates dropped from 5 of 542 (0.9%) to 0 of 460 (0%; P=0.039), indicating continued improvements in peri-procedural safety. The CAP2 registry of 578 patients supplemented the PREVAIL trial, with similar inclusion/exclusion criteria and protocol detailing. Patients in both CAP and CAP2 were at higher stroke risk with extensive comorbidities, yet had excellent procedural implantation success with lower complication rates. The lowest reported hemorrhagic stroke event rate was seen in the CAP registries (0.17 events per 100 patient-years in CAP and 0.09 events per 100 patient-years in CAP2), with low ischemic stroke event rates as well (1.30 events per 100 patient-years in CAP and 2.20 events per 100 patient-years in CAP2). Overall, the CAP/CAP2 registry data contribute more evidence that over time, the peri-procedural safety of the Watchman procedure is improving, though the data on efficacy in comparison to anticoagulation remains to be corroborated through further future randomized controlled trials.

A patient level meta-analysis evaluating bleeding outcomes for the 1,114 patients enrolled in PROTECT AF and PREVAIL over a median 3.1 years of follow-up was published by Price and colleagues. In this analysis, there were similar overall bleeding rates between patients treated with the Watchman device compared to those treated with medical therapy (3.5 vs. 3.6 events per 100 patient years, RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.66-1.40, p=0.84). However, when considering events occurring > 7 days post- randomization, there were significantly less events in the Watchman patients (1.8 vs. 3.6 events per 100 patient years, RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.32 – 0.75, p=0.001) with an even more significant difference noted after 6 months. This study demonstrates that the initial procedural risk is balanced by long-term benefit with regard to bleeding. In another meta-analysis of longer-term follow-up of both PROTECT AF and PREVAIL, while there was a trend toward a higher ischemic stroke rate in the Watchman group (p=0.08), the all-cause mortality was lower in the Watchman group (p=0.04) likely driven by the higher hemorrhagic and disabling/fatal stroke rate in the control group (p=0.0022 and p=0.04, respectively).

Currently, the Watchman FLX device is the latest, second-generation iteration of the Watchman device that consists of a self-expanding nitinol frame covered by a 160 µm polyester membrane on its atrial-facing side. Eighteen fixation barbs (versus 10 in the original Watchman) around the mid-perimeter secure the occluder to the wall of the left atrial appendage, reducing peri-device leak. The device is available in diameters ranging from 20–35 mm. Unlike earlier generations, Watchman FLX device has enfolded distal tines, dual-row anchors, more numerous struts, and reduced exposed metal (Figure 7). It has full recapture and repositioning capabilities, with multiple recaptures allowed. The enfolded tines also allow for the partially deployed device to form a “flexball” with a rounded end that can allow for atraumatic advancement to gain depth in the LAA during implant.

The safety and efficacy of the Watchman FLX device was evaluated in the PINNACLE FLX study (Protection Against Embolism for Nonvalvular AF Patients: Investigational Device Evaluation of the Watchman FLX LAA Closure Technology). This prospective, nonrandomized, multicenter study enrolled 400 patients with a mean age of 73.8 ± 8.6 years and a mean CHA2DS2-VASc score of 4.2±1.5. The primary safety endpoint was incidence of death, stroke, systemic embolism, or device- or procedure-related complications within 7 days of procedure or by hospital discharge (whichever occurred later). The efficacy endpoint was the presence of effective LAA closure defined as peri-device flow ≤ 5 mm at the 45-day and 12-month check-up. The performance goal of 4.2% was met for the primary safety endpoint, with a 0.5% incidence of safety events (2 patients, one ischemic stroke, one transient ischemic attack) (p < 0.0001). The performance goal of 97.0% was met for the primary effectiveness endpoint, with a 100% achievement of effective device closure (p < 0.0001). There were 7 patients with device-related thrombus; no patients experienced pericardial effusion requiring surgical drainage or device embolization. At a 2-year follow-up of 395 implanted patients, the secondary end point of 2-year stroke or systemic embolism was 3.4%, with an annual rate of 1.7%, surpassing the prespecified performance goal of 8.7%.

The overall results of PROTECT AF and PREVAIL studies suggest that LAA occlusion with the Watchman device is a reasonable alternative to warfarin therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation and elevated risk of cerebral events. One unknown that has been brought to light from these studies that has not been explored in a published, randomized trial to date is the role of LAAO in patients with contraindications to warfarin therapy. This question was delved into in the multicenter, prospective, nonrandomized ASA Plavix Feasibility with Watchman Left Atrial Appendage Closure Technology trial, in which patients received 6 months of dual-antiplatelet therapy followed by lifelong aspirin and no warfarin after Watchman placement. In this study, 150 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and a CHADS2 score of 2.8 ± 1.2 and a contraindication to oral anticoagulation (93% with history of hemorrhage or other bleeding tendency) were enrolled and followed for a mean 14.4 months post procedure. There were 6 cases noted of device-related thrombus (DRT), of which one was noted as a serious adverse event because it was associated with a stroke occurrence nearly a year post-implant. There were 4 patients with DRT that received 4-8 weeks of low molecular weight heparin, and the fifth case was managed without medication with no adverse event. Compared to an expected rate for ischemic stroke of 7.3% per year according to the CHADS2 score, patients undergoing LAA occlusion with the Watchman device had ischemic stroke rates of 1.7% per year. One patient suffered a hemorrhagic stroke (0.6% stroke rate per year). Adverse events occurred in 8.7% of patients and included bleeding, pericardial effusion and device thrombus/embolization. Overall, these results suggested that the Watchman device can be safely and effectively implanted without a warfarin bridge in patients with contraindications to warfarin therapy.

The EWOLUTION (Evaluating Real-Life Clinical Outcomes in Atrial Fibrillation Patients Receiving the Watchman Left Atrial Appendage Closure Technology) is another prospective, non-randomized, multicenter registry that examined the question of whether Watchman implantation was safe in patients with relative contraindications to anticoagulation (72%). The 1,020 patients from 47 centers were older with multiple comorbidities placing them at high risks for stroke and bleeding. There was a wide distribution in the postimplantation antithrombotic strategy used, with 60% receiving DAPT, 16% VKA, 11% NOACs, 7% antiplatelet monotherapy, and 6% receiving no treatment. During a median follow-up of 2 years, the stroke rate was 1.3% per year, with a combined end point of ischemic stroke, TIA, and systemic embolism rate of 2% per year, and 83% and 80% reduction in expected event rates in the untreated population. Furthermore, these rates are similar to the annual ischemic stroke rate (1.6%) and combined ischemic stroke, TIA, and systemic embolism rate (1.7%) from the combined data of PROTECT AF and PREVAIL, in which standard antithrombotic regimens were used. The rate of DRT in EWOLUTION, with its variable antithrombotic strategies, was 4.1%, whereas in comparison, the DRT rate in the combined analysis of PROTECT AF, CAP, PREVAIL, and CAP-2 was 3.7%. Overall, EWOLUTION showed consistent low stroke rates despite deviation from the traditional antithrombotic regimen, though this trial was limited by its lack of comparison group.

Designed to fill the knowledge gap of whether LAAO device placement is safe and efficacious in high-stroke risk (CHA2DS2-VASc score ≥ 2) patients ineligible for warfarin, The Assessment of the Watchman Device in Patients Unsuitable for Oral Anticoagulation (ASAP-TOO) trial is an ongoing prospective, randomized, multi-center, global trial enrolling up to 888 patients randomized in a 2:1 ratio of Watchman versus control. Control patients will receive antiplatelet monotherapy or no therapy. The anticipated results release is in December 2023. The primary safety endpoint encompasses the 7-day combined rate of all-cause death, cardiovascular accident, systemic embolism and periprocedural complication requiring surgery or endovascular intervention. The primary efficacy endpoint is measured as time to first ischemic event or systemic embolic event. Secondary outcome endpoints are the occurrence of cardiovascular death, ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, systemic embolism, and major bleeding.

In September 2022, the FDA approved DAPT usage for the Watchman FLX in light of data from prior trials and the LAAO Registry. Recent data discussed at Transcatheter Valve Therapy (TVT) 2022 comparing DAPT with aspirin plus an anticoagulant or warfarin after Watchman implantation showed no difference in deaths, strokes, major bleeding episodes, or DRT. Interestingly, DAPT has been an option after Watchman device placement since 2017 in European countries.

While most randomized trials to date have examined Watchman device placement in patients who are eligible for warfarin yet have reasons for pursuing mechanical antithrombotic treatments, the CHAMPION-AF clinical trial is randomizing approximately 3000 patients with atrial fibrillation to either the Watchman FLX or a NOAC in a direct comparison of the two strategies. Warfarin has largely fallen to the wayside as an anticoagulation comparator in trials due to its higher incidence of bleeding, including intracranial hemorrhage. In CHAMPION-AF, patients who are perfectly eligible for a NOAC but prefer an LAAO device will be compared with those who opt to take NOACs. The primary outcome measures are measuring noninferiority of the WATCHMAN FLX for occurrence of stroke, cardiovascular death, and systemic embolism, and superiority in regards to non-procedural bleeding. Results are expected in 2027. The only randomized controlled trial thus far to directly compare NOAC with LAAO (Watchman or Amulet) has been the PRAGUE-17 (Left Atrial Appendage Closure vs Novel Anticoagulation Agents in Atrial Fibrillation) trial. In this noninferiority trial, the primary endpoints were a composite of stroke, death, bleeding, and procedure-related complications and ultimately showed that at 20 months LAAO was noninferior to NOAC (95% apixaban). Because the trial was not powered to detect differences between the groups in the individual components of the primary endpoint, and because the benefits with regards to LAAO are seen in the long-term, the PRAGUE-17 authors conducted a 4-year follow-up of 402 patients. Again, there were no significant differences in long-term follow-up for all-stroke, TIA, cardiovascular mortality, or clinically relevant bleeding. However, when excluding bleeding events that occurred procedurally, the nonprocedural bleeding events were significantly reduced in the LAAO group (p = 0.049). In fact, a look back at a temporal analysis of bleeding events in PRAGUE-17 shows a separation in curves in favor of LAAO as early as 6 months. On balance, not only does this finding reinforce the commonly cited issues with long term anticoagulation, it further emphasizes the premium on procedural safety during LAAO to assure optimal long-term patient outcomes. Because PRAGUE-17 is underpowered, it is difficult to draw conclusions for the individual endpoints such as stroke rate. The projected higher power of CHAMPION-AF should shed further light on the question of the individual risks and benefits of LAAO versus NOAC.

Amplatzer devices

First use of the Amplatzer Septal Occluder (ASO) began in 2002, around the same time as the Watchman. Originally designed for atrial septal defect closure with a double disk mechanism (one disk for the left atrial side and one for the right atrial side), the ASO was serendipitously discovered to fit into the LAA when the left disk was accidentally deployed in the LAA and then became difficult to remove. With knowledge of the original difficulties of the PLAATO device, it was thought that ASO placement would be a much simpler technique given its success for ASD closure. Thus, the ASO was regeared for LAAO, and the Bern technique was developed based on the pacifier principle. Reminiscent of a pacifier, the final orientation of the ASO using the Bern technique is such that the left-sided disk sits lodged in the LAA and the right-sided disk faces the atrial chamber. Meier et al., reported on the first 16 patients who underwent LAA occlusion with this device. Implantation was successful in 15 patients with one patient experiencing device embolization (device larger than appendage) with uneventful surgical removal and right/left appendage obliteration. During follow-up, complete occlusion was noted in all remaining 15 patients with no further complicating events. However, in 100 patients, the acute embolization rate was 10% so the technique was abandoned and the device was redesigned for tailored LAAO usage.

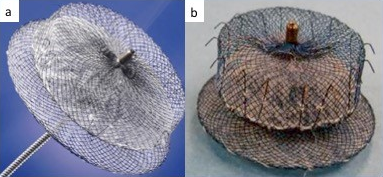

The Amplatzer Cardiac Plug (ACP) (Figure 9 a) was the brainchild of the reengineering efforts, receiving CE mark approval in 2008. Designed as a double-seal structure, it consists of a distal lobe with a proximal disk connected by a flexible central waist. Procedurally, the distal lobe is positioned within the left atrial appendage and the proximal disc is angled to fully cover the orifice of the left atrial appendage. Six pairs of hooks are attached to the distal body enabling the occluder to engage the wall of the left atrial appendage. The device is fully repositionable and recapturable. Device sizing is with reference to the distal lobe and ranges from 16-30 mm in 2 mm increments. The proximal disks are 4 mm larger for lobe sizes 16-22 mm and 6 mm larger for lobe sizes 24-30 mm. Appropriate sizing is 10-20% larger than the minimum appendage orifice measurement by TEE.

Figure 9

Amplatzer Cardiac Plug (left) and Amulet Device (right)

The initial European experience with ACP was reported for 143 European patients with atrial fibrillation. Device implantation was successful in 132/137 (96%) attempted implants. Serious adverse events occurred within 24 hours in 10 (7%) of patients. These events included 3 cerebral events, 2 device embolizations and 5 pericardial effusions requiring drainage. Subsequently, Kefer et al., reported their experience of 60 patients with atrial fibrillation (CHADS2VASc 4.4±1.8, HAS-BLED 3.3±1.3) undergoing LAA appendage occlusion with the ACP device. The device was successfully implanted in 59 patients with 3 cases of tamponade, 3 smaller effusions, 2 cases of air embolism and 1 pseudoaneurysm. Over 1 year follow-up, the rate of stroke was 2.14%/yr. For patients with contraindications to anticoagulation, Wiebe et al., reported their experience with 60 patients (CHADS2VASc 4.3±1.7, HAS-BLED 3.3±1.0) undergoing LAA occlusion with the ACP device. The procedure was successful in all but 3 patients. Over a mean of 1.8 years follow-up (1.0-2.8), no patients experienced stroke. Most recently, Tzikas et al., reported experience with the first generation Amplatzer cardiac plug in 22 centers involving 1,047 patients. Procedure success rate was high at 97%, and overall periprocedural complications were low at 4.3% (death, tamponade, stroke, bleeding, myocardial infarction, and device failure). On follow up, the observed stroke rate was 2.3% versus an expected 5.62% based on CHADS2VASc score risk stratification with an overall reduction of 59%.

Amulet

The Amulet (Figure 9 b) is an iterative design advance on the original ACP device. Modifications of the Amulet include preloading for enhanced ease of use, availability of 31 and 34 mm sizes that allows for closure of a wider range of LAA diameters (11- 31 mm), a longer waist and greater number of fixation wires to enhance stability and a recessed pin to minimize thrombus formation. The first-in-man evaluation of this second-generation LAAO device included 25 patients with atrial fibrillation and a mean CHA2DS2VASc score of 4.3 +/- 1.7 undergoing LAA occlusion with the Amulet device. Procedural success was 96% with no procedural complications and complete closure in all patients. One patient experienced device-related thrombus with no clinical consequence. These findings led to CE approval in early 2013. A head-to-head comparison of the Amulet and ACP devices was performed in 59 patients (31 ACP, 28 Amulet). There were no differences in procedural success or device related complications, but less patients in the Amulet group had any form of residual leak on follow-up TEE (8% Amulet vs. 48% ACP, p=0.01).

Because the LAA has a wide range of morphologies, it was hypothesized that the dual-seal mechanism of the Amulet may be more robust in closing the appendage than the single-seal mechanism of the Watchman. In order to provide a head-to-head comparison of the safety and effectiveness of the first-generation single-seal Watchman with the second-generation double-seal Amulet, the recent Amplatzer Amulet Left Atrial Appendage Occluder Versus Watchman Device for Stroke Prophylaxis (Amulet Investigational Device Exemption (IDE)) trial was completed and published in 2021 as the first large-scale, multicenter, randomized-controlled trial of 1878 patients, paving the way for U.S. FDA approval of the device in August 2021. The Amulet was found to be noninferior to the Watchman for the primary safety endpoint (a composite of procedure-related complications, all-cause mortality, or major bleeding at one year) ((14.5% versus 14.7%; difference=–0.14 [95% CI, –3.42 to3.13]; P<0.001 for noninferiority). Additionally, it was noninferior to the Watchman device for the primary effectiveness endpoint (composite rate of cerebral vascular accident, systemic embolism, or cardiovascular death (5.6% versus 7.7%, difference=–2.12 [95% CI, –4.45 to0.21]; P<0.001 for noninferiority) and the composite of rate of ischemic stroke or systemic embolism (2.8% versus 2.8%; difference=0.00 [95% CI, –1.55 to1.55]; P<0.001 for noninferiority).

Effectiveness was also measured as successful left atrial appendage occlusion with residual jet ≤5 mm at 45 days on TEE, with 98.9% of patients with the Amulet meeting this threshold compared with 96.8% of Watchman patients (difference, 2.03 [95%CI], 0.41–3.66]; P<0.001 for noninferiority, P=0.003 for superiority). Total occlusion with no residual jet was found in 63.0% of Amulet patients and 46.1% of Watchman patients. There were higher rates of procedural complications (pericardial effusion and device embolization) for the Amulet versus Watchman (4.5% versus 2.5%), which decreased with operator experience. Physicians outside the United States were more familiar with the implantation process of Amulet, and American physicians were provided an opportunity prior to the trial to implant up to 3 Amulets to gain experience. Rates of major bleeding were similar between Amulet (11.6%) and Watchman (12.3%) (P=0.32) and thus the secondary endpoint of superiority was not met.