Ethics in cardiovascular interventions

Summary

Moral teaching involves decisions about right and wrong based on shared values and norms in a given society. Ethics is the study of morality in a given context. Finally, the law represents a set of rules of conduct systematised and enforced by society. Thus, in a nutshell, ethics addresses moral obligations often outlined in moral teaching while the law defines legal duties. In order to follow the principles of Good Medical Practice all three domains need to inform decision-making, and their respective missions should be clearly understood by all professionals and organisations involved in health care.

This chapter provides a brief overview of medical ethics with a focus on the practice of cardiovascular interventions.

Introduction

Ethics is the study of morality, and involves the rights and wrongs in human decisions and actions in a given society. Ancient writings as diverse as the Vedas, Bible, and Analects, and the various codes and codices of long-gone societies testify to the origins of ethics as rule-based entities designed to establish and maintain order and civility within the emerging societies. Later these rules became the subject of religious, political and philosophical debates, eventually resulting in the development of numerous schools of philosophical ethics, and, at least partly, inspiring the parallel development of legal systems.

Three main concepts of ethics are distinguished in the Western world, all based on cultural tradition from Ancient Greece: teleology (telos; Greek for end, purpose, goal), deontology (deon; obligation, duty; and logia; teaching, body of knowledge) and virtue ethics. The first derives its authority from the primacy of ends over intentions; the second puts the intentions of actions first; and the third emphasises the expertise of the decision maker. Commencing with the teachings of Plato (428-348 BCE) and Aristotle (384-322 BCA) expressing the ideals of eudaimonia (happiness, well-being, flow) resulting from human virtues, a number of schools of ethics in teleology or deontology traditions have emerged targeting the systematic and coherent justification of morality. Philosophers working on both meta-ethics and normative ethics dispute their underpinnings and codification - if one is possible (particularists deny this, principlists affirm it) - of moral or ethical judgements. Consequentialists think, generally, that acts are good if they produce good outcomes. Deontologists think that their goodness depends on the right intentions of the actor, behaving in accordance with duty coded as principles. Virtue ethicists think that actions are good if they are the actions of a virtuous agent balancing competing factors in a way that may resist codification. A number of schools of ethics have emerged within each main branch, emphasising their distinct interpretations and justifications of morality [see Appendix A].

Medical ethics relies largely on deontology, but also includes considerations based on consequentialist and virtue ethics. Medical ethics were once regarded as relatively straight forward and common place, and firmly placed in the practice of medicine, but they have more recently become the subject of reality testing and deep scrutiny. Rapid changes in world’s geopolitics, environmental protection policies and other global factors mean the practice of medicine has also profoundly changed. The departure from the traditional paternalism guiding physician-patient relationships for millennia, the growing emphasis on legal protection of patient rights, calls for greater transparency in increasingly managed and pro-profit health care, the impact of eHealth and emergence of artificial intelligence and information technology, including big data analytics, are but a few of the changes. Along with economic and environmental global conflicts the protection of human rights and human rights abuses has also been placed centre stage. These sea changes in the governance of modern and developing societies characterized by the growing instability of global political and economic orders, means that ethics is becoming central to these conflicts and must be visibly moving from philosophical theory into real-life practice.

Over the past several centuries the essential principles of morality have become integral parts of civil codes in Europe and the majority of people take these principles for granted. Thus, the pursuit of medical ethics does not require extensive study of moral philosophy, but acquaintance with the basic tenets is recommended , , .

With the rapidly changing landscape of modern medicine it is now obvious that casual acquaintance with the traditional maxims of medical ethics will no longer suffice. Far more is needed to sustain ethics of good faith in health care. Doctors need to be keenly aware of those multiple changes and their impact on medical practice. A thorough understanding of professional duties and obligations, along with applied legal framework protecting patients, are required to uphold ethical integrity of medical profession. This is particularly true in interventional cardiovascular medicine where risk of harm to the patient is common and full ethical and legal accountability of the operators is imperative .

This chapter briefly reviews some of the key ethical considerations and legal implications relevant to the practice of interventional cardiovascular medicine. The specialised literature should be consulted for more extensive treatment , .

Ethics: Principles

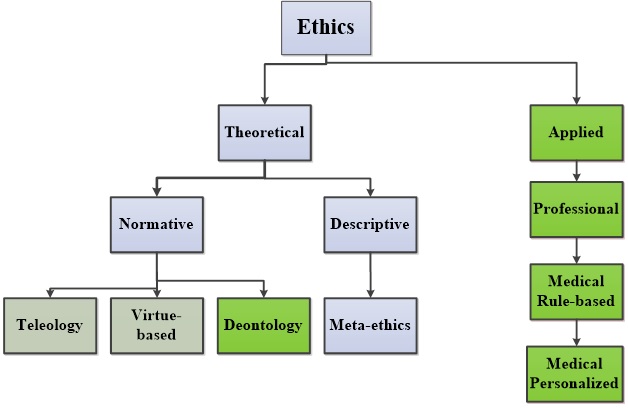

Ethics explores questions of morality; the goodness of decisions and actions. Metaethics examines the nature of, or principles governing, goodness and wrongness. Normative ethics strives to develop a comprehensive system of rules of ethical conduct free of contradictions and inconsistencies. There are also, however, theoretical normative perspectives that deny the possibility of congruous, conflict-free and comprehensive narratives of moral conduct. Facing countless dilemmas resulting from human frailty and fallibility in combat with the sea of uncertainties characterising the human condition, applied ethics is concerned with moral right and wrong in pragmatic decisions. A close examination of facts, weighting of arguments, trade-offs between the interests of different stakeholders and a readiness to make concessions and compromise are required in order to make ethical judgments in real-life conflicts. Applied professional ethics introduces the contingent features of the roles of professions as extra premises to whatever normative approach one might adopt. Typically, this is summarised in codes of professional conduct regulating professional duties and obligations. Professionals are expected to read, understand and follow written codes and policies. Applied professional ethics in medicine essentially recapitulates the principles of normative ethics, adapted to the needs of current medical practice, by codifying the rules of conduct for health care professionals. While the main doctrine is based on deontology, consequentialist and virtue ethical perspectives are also adopted in practice. Personalised professional medical ethics refers to the actual state of ethics as practiced by individual doctors. Personalised professional medical ethics is the format of ethics that matters to patients, the public and society the most, by reflecting the ethical integrity of individual doctors and mirroring the ethical standing of the medical community. Figure 1 provides an overview of ethical categories.

Figure 1

Overview of normative and applied ethics’s categories. Categories of ethics based on nomenclature employed in philosophical literature (blue) and categories particularly relevant to medical ethics (green) are shown.

Medical and Biomedical Ethics: Historical Outline

In the Western moral tradition, ethical principles such as justice and fairness have become elements of constitutional human rights, and thus increasingly also elements of common sense. Patient rights to health, autonomy, safety and well-being are becoming statutory .

Medical ethics, traditionally associated with the texts of the Hippocratic corpus, and particularly that of the Hippocratic Oath, has in modern context far more recent roots. Thus, John Gregory (1724-1773), Professor of Medicine at the University of Edinburgh and student of the philosophy of Francis Bacon (1561-1626) and David Hume (1711-1776) along with Benjamin Rush (1745-1813) and Thomas Percival (1740-1804) may be considered the founders of modern medical ethics [see Appendix B]. The establishment of the Committee on the Ethics of the Medico-Chirurgical Society of Baltimore in 1832 and the inauguration of the Code of Ethics by the American Medical Association in 1847 are considered major milestones in the development of the medical ethics, particularly within the Anglo-Saxon tradition. Later, in response to the crimes against humanity committed during World War II, the newly forming global community launched a number of initiatives to forestall such crimes in the future. The Declaration of Geneva restated the ethical obligations of physicians, updating the Hippocratic Oath to a contemporary context. Although the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, drafted under the auspices of Eleanor Roosevelt, stressed the political dimension of future democratic humane societies, it was Nuremberg Code of 1947, reinforced by the International Code of Medical Ethics of the World Medical Association in 1949, and the Declaration of Helsinki in 1964, with the most recent amendment in 2013, which defined the rules of conduct concerning medical research and a patient’s rights [Table 1].

Table 1

Bioethics, a term introduced in the 1970s by Van Rensselaer Potter II (1911-2001) addresses issues arising from conflicts between biosciences and the humanities. In fact, Potter termed bioethics the science of survival . Today, bioethics is an all-inclusive field concerned with the ethical questions accompanying biomedical research and progress in medicine. Appendix B and Appendix C provide some historical background concerning the development of medical ethics.

Medical Ethics: Principles

While the main mission of medicine is the prevention of disease, the restoration and maintenance of health, and the prolongation of life, the main objective of medical ethics is to ensure that this mission is accomplished while conforming to standards of ethics.

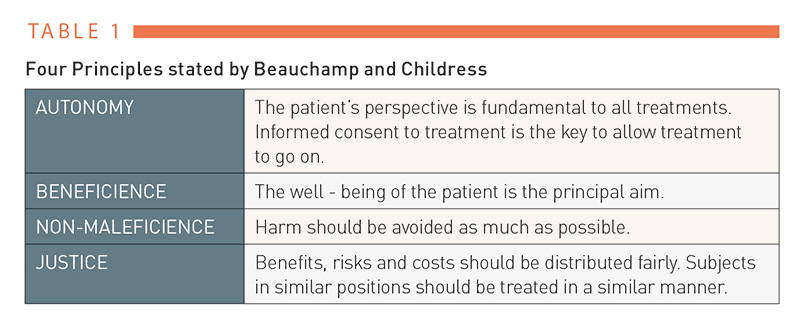

Medical ethics is bound by the maxims of theoretical ethics, which are based on the fairness, goodness and justice of human actions. Beauchamp and Childress famously formulated four principles to govern biomedicine and medical practice, in order to capture the essence of the maxims of theoretical ethics relevant to bioethics [Table 2] . These four principles, also termed ‘principlism’, are supposed to capture the essence of medical ethical reasoning. Nevertheless, even this small number of principles may be in conflict. Because each of the four principles is axiomatic and not derived from a single “first” principle, they need both ‘balancing’ and further ‘specification’ when applied to individual real-life cases. Classically, in medicine, beneficence and non-maleficence are always in tension due to the possibility of harm. Determining which principle should dominate in any particular context requires patient- and situation-specific judgment, suggesting that, ultimately, the four principles approach collapses into particularism. The ‘principles’ are thus not really principles governing a judgment, but rather maxims and helpful reminders for what it is wise to consider in a particular case.

Table 2

Broadening the scope of ethical consideration through the inclusion of a multiplicity of principles, such as “people’s rights and claims, different sorts of interests and their relative strength, human well-being , loss of life, what would be good or bad for people, democratic acceptance, consultation, sensitive moments, benefits and harms, grief and distress, an obligation to make sacrifices for the community, an entitlement of the community to deny autonomy and even to violate bodily integrity in the public interest, the system of justice, public safety, public policy considerations, danger, civil liberties, individual autonomy, and saving and protecting the lives and liberties of citizens” , may not necessarily be practical in resolving particular ethical conflicts. On the contrary, with the increasing number of potentially, but not necessarily, relevant issues to be considered, the complexity of decision making may seriously impede due process.

Corollary inference

The rapid progress in medicine spanning several decades has swayed the focus of bioethics towards the grand and most visible issues, such as organ donation, human enhancement, manipulation of the human genome and stem cell therapy while the rapidly changing bioethics of day-to-day medical practice and health care delivery received at the same time far lesser attention by comparison. In addition, in Europe medical ethics has become an arbiter between different health care stake holders while side-tracking the patients. Thus, with the onset of the

SARS-CoV-2 pandemic physicians facing the gathering storm of emergencies and ethical dilemmas were caught unprepared having to rely on their own conscience and otherwise left to their own devices. The war in Ukraine along with the accelerating global ecological, climate and migration crisis will also in Europe refocus medical ethics on delivery of patient care, as it seems outside of the as of now customary comfort zone. In economically less advanced countries the preoccupation with, poverty, destitution, famine and scarcity determines the agenda of medical ethics.

Medical Ethics: Physician-patient relationship in the past

The physician-patient relationship in the Western cultural tradition and probably elsewhere is as old as the medical profession. In the pre-Socratic era (7th-5th century BC) the relationship seemed to be dominated by archaic elements of magic and mystery. During the subsequent Classical Age, which includes the Socratic (5th–4th century BC) and Hellenistic (3rd century BC – 3rd AD) ages, and partly overlaps with the Roman period (1st century BC- ca. 5th century AD) the “physician’s technique” asserting an early understanding of physiology, pharmacology and pathology emerged. The relation was characterized as friendship (philia) based on benevolence and discretion of the physician. The physician seemed to be motivated by altruism (philanthropia or charity towards other humans) and love for the art of healing (philotechnia). The patient was expected to trust the physician and to follow his advice. Such friendship, however, represented an ideal format, and applied only to free and independently rich citizens. Free but poor residents, and slaves, seemed to have been treated by less respected acolytes in a less formal fashion .

During the Christian epoch and during the emerging Scholasticism (ca. 11th – early 18th century AD) transition from physicians obedient to the omniscient God to physicians trained in universities – the oldest was the University of Bologna in 1088 AD, with a School of Medicine and Surgery opening in 1200 AD (11) – and increasingly applying rational means occurred. However, the development of the medical profession along with the physician-patient relationship during the early dominant and then the waning era of Christian dogma is complex and have been detailed in the literature , .

With the progressive secularisation of world views, propelled by the first scientific revolution (16th-17th centuries) and the ensuing Age of Enlightenment dominating in Europe (17th-18th centuries) the rational approach to medicine has increasingly gained acceptance and traction [Appendix B]. Technical progress and expanding knowledge have brought about the growing emancipation of the medical profession. Along with the progressive liberation of citizens, the physician-patient relationship based on fellowship rather than former friendship emerged.

With the foundation of professional medical societies beginning in the 19th century developing against the background of the second (19th century) and the third (20th century) scientific revolutions the practice of medicine and the character of the physician-patient relationship has changed again. Practice of medicine increasingly based on advances in physiology, pathology and emerging new medical sciences and stipulation of duties and obligations the physician-patient relationship became more formal, regulated and technical. The spread of eHealth services is likely to have profound impact on the physician-patient relationship known today. The consequences of gradually replacing the direct human-to-human contact embodied in the physician-patient relationship by digital communication platforms remain as yet unexplored.

Medical Ethics: Physician-patient relationship now

Today the physician-patient relationship is considered an association between two rational human beings with common and mutually binding objective being preservation and/or restoration of patient’s health. In essence, the physician-patient relationship has a fiduciary character with the physician (trustee) and patient (beneficiary) founded on mutual trust. The physician (fiduciary) is expected to uphold professionalism by delivering on promise of treatments in good faith according to the accepted medical standards in the best interest of the patient. The relationship has a formal character of covenant rather than contract. While the law does not explicitly interfere with the essentially trust-based principle of the relationship it guards over its appropriateness. In cases of transgressions largely the codes of the civil law and, far less frequently, those of the criminal law apply .

The physician-patient relationship fuses two perspectives. Physician besides caring for the patient has over time become more and more burdened by multiple new tasks and new duties that are often only indirectly related or even foreign to patient care. In consequence, physicians increasingly struggle to keep up with those demands leaving less time for the actual patient care. In contrast, patients’ expectations to receive the best available professional help and advice when ill have not changed much over time. Patients’ insights into the physicians’ quandaries as a result of the rapidly changing landscape of the increasingly externally managed health care may or may not mitigate expectations.

Physician perspective

The codes of medical ethics stipulate that all treatments must be conducted in good faith and in the best interest of the patient. The premise of good faith with the caveat of professional expertise is unconditional. Treatments conducted otherwise are considered unlawful transgressions and become subject to legal prosecutions. In contrast, the term in the best interest is opaque and requires qualification. Thus, in theory, the best interest is best served when treatments are performed by the best experts using unlimited resources and achieving optimum outcomes at no risk to the patient. In practice, however, these ideal conditions are never met and the best interest is always a result of a compromise. The physician is obliged to acknowledge the existing limitations and to explain them to the patients. In addition, however, the physician also needs to learn to understand the perception of the best interest of individual patients. Based on preferences, expectations, values and risk attitudes of individual patients the physician may formulate and outline the course of treatment considered that could be considered in the best interest of the patient. During the dialogue the physician and the patient should agree on a realistic plan of the treatment. To follow through with the plan and to overcome possible adversities mutual trust is essential and face-to-face with the patient does or does not the trick. Thus, the face-to-face should be conducted with due respect to the disposition and personality of the patient in an open, fair and square manner. Empathy and sensitivity towards the individuality of the patient carry a long way, provided they were honest and sincere. Explicit and implicit sympathy is a hallmark of the fellowship with the patient. The trusted physician is indeed a friend in need. Potentially embarrassing issues such as the question of financial compensation, if not regulated, are part of the covenant and should be also discussed in an open and straightforward fashion.

Personalized and precision medicine has become a catchphrase suggesting custom made treatment to all patients. While technical progress already delivers on this promise in small steps the humanitarian and ethical aspects of the project seem to be lacking far behind. To narrow the gap application of the principles of medical ethics in clinical practice and particularly realized in physician-patient relationships will become a crucial next step.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASES

Case 1.

T.E. is a brilliant surgeon. He was a trained and educated all-rounder, and embarked on highly successful career as an attending physician and eventually physician-in-chief. Recently, we spoke over the phone some 45 years after we first met. Rather casually T.E. mentioned that in 1991 he founded a non-profit organisation dedicated to providing medical services for countries of need. The organisation operates predominantly in the countries of the Sahel region, such as Yemen and Mali. Following his retirement in 2005, T.E. resumed a two-week on and two-week off regime of free-of-charge work in those countries that is still ongoing. Asked if he used extra time to visit the country’s sites, T.E.’s answer was no. He does only work on his assignments and when two weeks are over, he leaves. Following a vacation in his homeland, Greece, T.E.’s next stop is Burkina Faso. T.E. is 83 years old.

Case 2.

M.H. is a leader in his medical field. He is a successful clinical researcher, director of a large university hospital and associated research institutes, as well as a community leader with plentiful academic acclamations and public responsibilities. What is it like to be a patient of this busy physician? Following a call to his office requesting personal advice, the next day, Friday 6pm, the phone is ringing. M.H. is on the line. His voice is welcoming. He readily provides the requested advice, followed by a friendly chat about all and sundry.

Case 3.

A 14 year old girl suffers from a heavy cough for an extensive period of time. Finally, she and her mother decide to consult a GP. The physician listens to the girl’s chest and orders a chest X-ray. The film shows patchy infiltrates, diffusely involving both lungs. The GP’s verdict is cancer, and this is bluntly communicated to the patient and her mother. Both child and mother leave the office in a hurry and alarm, and with no advice about what to do next. Following frantic internet searches on lung cancer in children they decide to ask another GP for a second opinion. The correct diagnosis, pronounced a day later, was atypical pneumonia with speedy recovery, which was gently expressed, and calmed the patient and her mother.

Patient perspective

According to the WHO health is defined “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity." This claim represents an ideal state. In practice, however, health is a state compatible with normal life free of pain and suffering. Impaired health prompts the patient to seek medical help.

It is important to note that the diseases described in textbooks differ from illnesses experienced by patients. Depending on patient’s personality the same disease may produce different illness in different patients. Alarmed by the symptoms the patient wishes to regain health in the most expedient way. “We know what we have had only after we have lost it” counts doubly in matters of health. In fact, the concerns about one’s own health mostly override all other immediate concerns.

In decisions to seek medical help are particularly two factors important; firstly, fears, worries and concerns, and secondly, feelings of helplessness. Due to the intimate nature and importance of health the question of where to turn for help becomes quickly question of trust. Can I trust this doctor? is then the key question.

Choice of the physician [Table 3] and trust in the physician-patient relationship [Table 4] depend on multiple factors. Although professional expertise is the most important factor for outcome it is hard to be found and the methods of search range from the hearsay to the internet page. Due to the lack of medical insight the search becomes often simply a matter of good or bad luck. In contrast, trustworthiness does not require medical knowledge allowing the patient to decide based on their impressions concerning the physician. Given the importance and intimacy of health the need of help heightens the patient’s sensibility to the personality traits of that medical professional. Trust or distrust represents summary result of interaction between two human beings discussing a plan addressing a serious life matter. Being truthful represents only a part of the interaction (13), being wise is the jackpot.

Table 3

Table 4

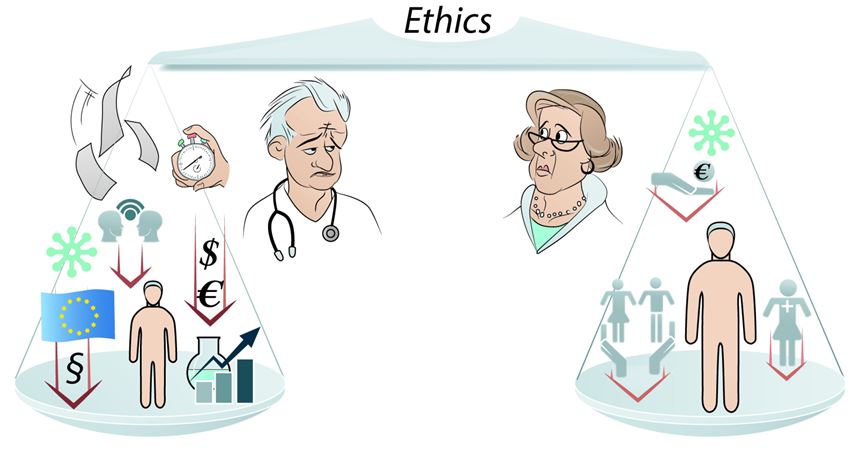

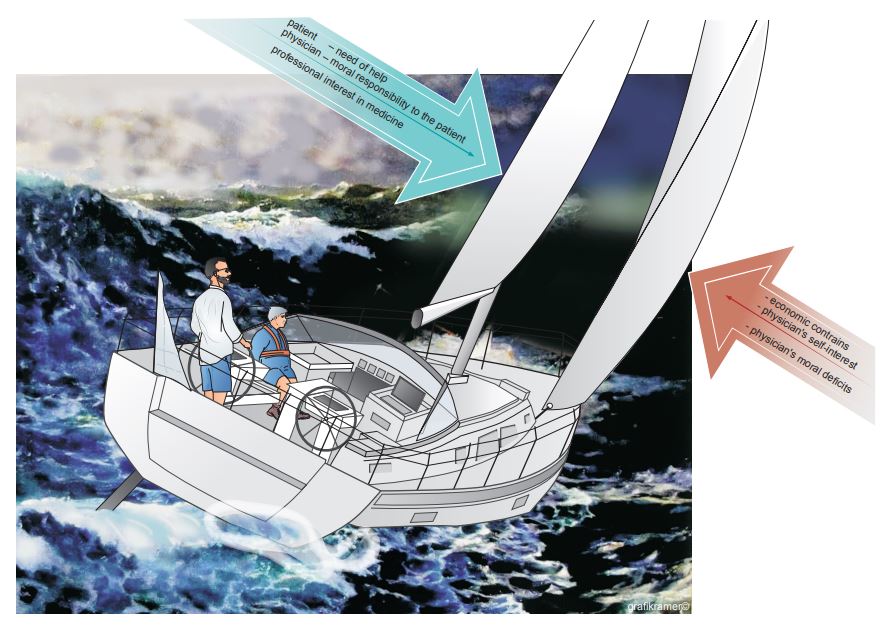

The presently observed human fellowship on the run and at the losing side of the coin must be rescued and regained. Applied ethics are the means to accomplish the task and saving the medicine’s humanitarian mission. Figure 2 summarizes the differences between physician’s and patient’s perspectives. Figure 3 shows the physician and patient sailing in the same boat bound by professionalism and human fellowship surrounded by the real world’s stormy weather and rough seas.

Figure 2

Shown are the two perspectives within the physician-patient relationship. The perspective of the physician is characterized by increasing number of duties and obligations, partly not related or even possibly competing or conflicting with patient’s best interest, resulting in progressive lessening of patient’s central importance. The perspective of the patient is timeless determined by worries of one’s own health and preservation of economic welfare (Lanzer P. Eur Heart J 2022;43:1027-1028; with permission).

Figure 3

Shown is physician-patient relationship exposed to external forces. Both physician and patient share the same boat. Their boat is driven by favourable (green) and adverse (red) forces, largely within the physician’s control. In addition, however, the boat is exposed to the stormy forces of global political, economic and environmental factors that are far beyond control of the physician and the patient.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

Consider the case of a young patient scheduled for elective transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI). A new valve that is marketed for excellent short-term outcomes becomes available, but the long-term durability of the device is unknown. The operator is keen to gain experience with the new technology and wants to implant the device, but, acknowledging the incompleteness of evidence, they do not know what is in the best interest of the patient. Despite this, a decision must ultimately be made. Typically, the team is involved in the decision process, and the patient given detailed information in order to resolve the doctor’s dilemma. Nonetheless, the validity of the recommendation and the soundness of the decision will remain uncertain. Yet, conditions of mutual trust have been established.

Medical and Biomedical Ethics; Tool Box – Informed consent

The internationally recognised Nuremberg Code, which posits the inviolability of a patient’s right to autonomy and physical integrity “for all times”, was followed by a series of declarations in the wake of the Nuremberg trials, further expanding those rights [Appendix B, Appendix C].

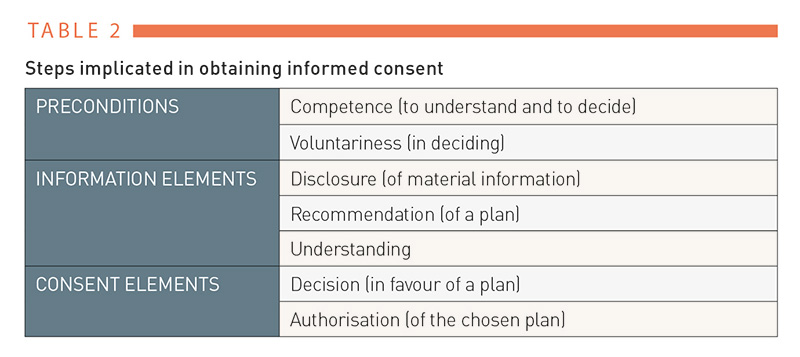

Along with the expansion and codification of patient rights, the formal principles of informed consent were developed. A patient’s education and the process of consenting, formerly informal, are now written legal documents confirming patient’s autonomy and self-determination. The patient’s education preceding the informed consent should mitigate the asymmetry of medical knowledge between the physician and the patient. Following the education the patients should be better prepared to make an informed decision regarding the proposed course of the treatment. As corollary, the patient should be empowered and motivated to become an active participant and partner in the healing or palliative process. According to current laws, medical treatment is seen as an injury representing a criminal offense unless explicit informed consent has been obtained; only valid informed consent legalises treatments. Although informed consent is not a legal contract, it is a promise of medical service enforceable by law and endowed with a legal power of veto.

According to the recommended EU definition, Informed Consent is the decision, which must be written, dated and signed, to take part in a clinical trial, taken freely after being duly informed of its nature, significance, implications and risks and appropriately documented, by any person capable of giving consent or, where the person is not capable of giving consent, by their legal representative; if the person concerned is unable to write, oral consent in the presence of at least one witness may be given in exceptional cases, as provided for in national legislation .

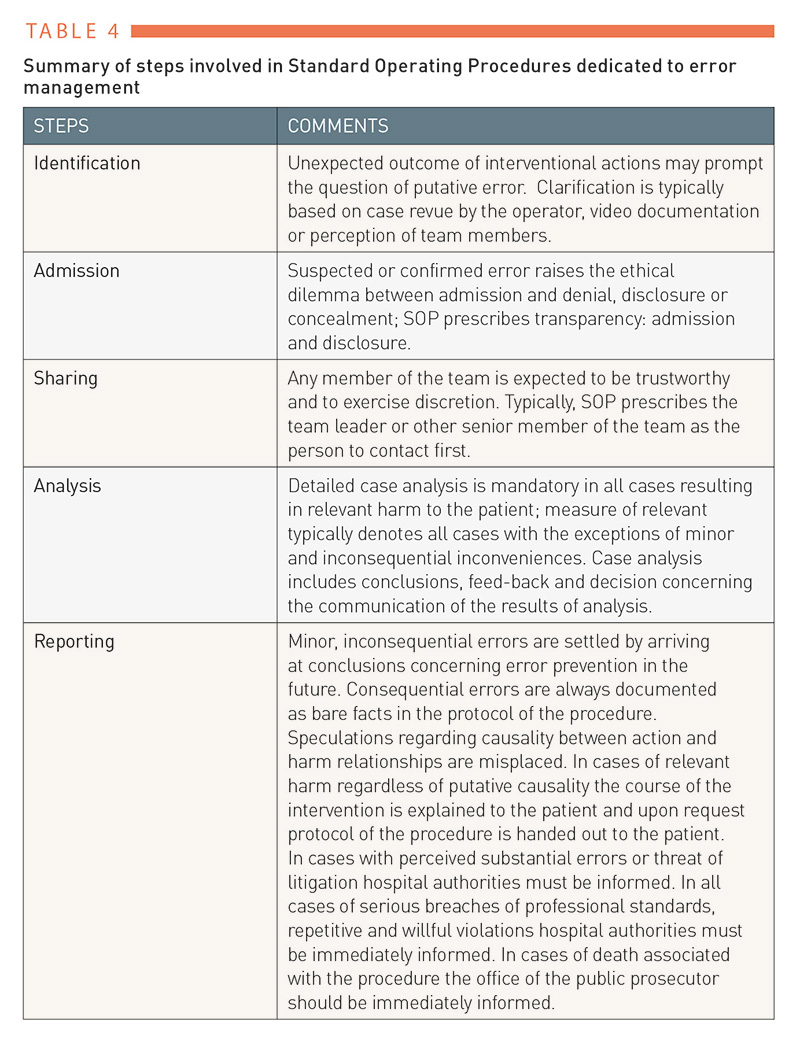

Informed consent applies to all medical actions, including diagnostic tests. In the printed informed consent forms the general information regarding the intended procedure is provided. Procedure related considerations concerning individual patients need to be addressed and to complete the informed consent explicated and put down in writing. Importantly, all relevant procedural risks need to be stated. This provision is particularly important in all endovascular procedures. The steps required to obtain valid IC are summarised in Table 5 ().

Table 5

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

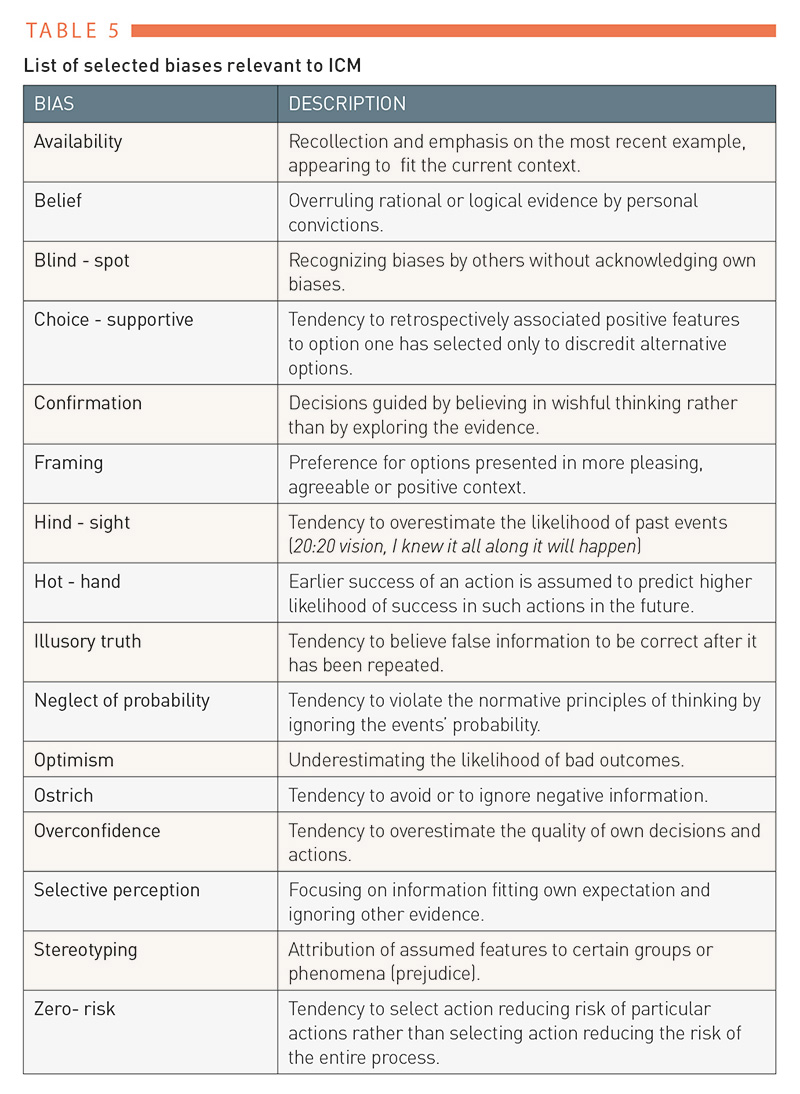

Consider the case of an elderly patient with stable ischemic coronary artery disease and a moderate cardiovascular risk profile, including type 2 diabetes with known three-vessel coronary disease and no exertional angina, on the medication recommended by current guidelines with 20% left ventricular mass myocardial ischemia on Thallium-201 myocardial scintigraphy. The patient consults their cardiologist and asks to have the best treatment based on available evidence. Given the available data (status April 2020; DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1915922; DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1916370) there is no conclusive evidence in the definite favour of either conservative or invasive management with regard to the primary and secondary endpoints. Further, given the sensitivity of outcomes in studies with respect to the definition of myocardial infarction, further complicating the interpretation of results, advice to the patient will likely be equivocal, if strictly evidence-based. To reach consensus and to make a decision fulfilling the criteria of professional ethics, the patient requires an explanation of the data ambiguity preventing any straight forward recommendation. The doctor’s task will be to explore the factors present in a given context with the patient. These factors may include the potential relevance of absence of angina in patients with diabetes, potential long-term impact of ischemia on myocardial function, procedural risks and risk factors related specifically to this patient, including left ventricular function, presence of panvascular status, co-morbidities, experience of the operator performing the procedure and so on, depending on the context and the patient’s expectations and preferences. Clearly, fully objective and bias-free communication is the ideal, not the realistic, scenario. While a cardiologist may lean towards the conservative option, an interventional cardiologist may be more likely to recommend coronary revascularisation. Professional ethics requires an awareness and control of personal biases. Decisions should be based on a careful weighing of pros and cons in the best interest of each individual patient. Realistic and clear presentation and a close rapport with the patient characterise fair and truly personalised medical practice.

Prior to consenting, patients must be educated concerning the rationale, necessity, urgency, suitability and effectiveness of the intended treatment. Effective and valid patient education should allow a patient to make informed decisions concerning all intended medical actions based on the explanations provided. These explanations should include all relevant procedural steps, including diagnostics, treatments, risks, and also any alternatives to the suggested treatment .

Patient education in planning of diagnostic procedures should include a description of all intended diagnostic measures. A patient is entitled to a full disclosure of all results and diagnostic findings. Patient education in planning of treatments should include a justification of the recommended medical action, and the pros and cons of this and alternative treatment options, particularly in regard to benefit and risk evaluation. The probability and magnitude of the risk of harm and the plan for the intended procedure should be explained to, and understood by, the patient. Full education about risks is considered the most essential step in ascertaining the patient’s consent and acceptance of risks expressing the right to self-determination. Patient education about alternatives should include fair information about other therapy options, supported by evidence. Fairness in weighing of the pros and cons of each of the relevant alternatives is expected. It should be understood that fully educated judgments of patients about the expected risks and benefits of intended measures represent the ideal maxim.

Limits of education are set by the probabilistic nature of outcomes and often by the procedural complexity. In addition, patient’s mental capabilities to understand the course of treatments may be also limiting. The test of mental capability codified by law is that a patient is able to understand and retain the information required to arrive at an informed decision, to believe the information and to weigh it so as to make their own choice, and to communicate their decision . Basic patient education must be performed even for patients with marked cognitive limitations. Life-saving procedures are usually prioritised over detailed education in urgent and emergency interventions. Extensive and detailed education is required when procedures deviate from established standards, and when new medical treatments are involved.

The physician performing the intervention can delegate patient education to another physician who is sufficiently knowledgeable about the scope of the intended treatment; however, it is recommended that particularly in procedures associated with relevant risk the education is conducted by the operator. Regardless of the arrangement the ultimate responsibility rests in all cases with the operator. Delegation of education to other medical personnel such as nurses is not permissible.

Patient education should be conducted in comprehensible manner. Technical terms should be expressed in lay language, and, as far as possible, adequately explained. Patient education should take place well before the time of the intended procedure allowing sufficient time for the patient “to think the things over” and to make deliberate decision. Commonly ‘over-night’ time or 24 hours is considered adequate. Shorter time periods are acceptable before minor procedures. The consenting patient should be mentally capable of comprehending the meaning of the intended medical action. Paternalism in speech is misplaced and should not be used. The patient should be encouraged to ask questions to clarify open issues. Asking questions enables the physician to ensure that the patient has understood the aim and the plan of the treatment. For standard procedures printed informed consent forms are available and should be distributed prior to the education familiarize the patient with the procedure in question. A date and signature are necessary to validate any written informed consent.

Medical treatments provided without informed consent are only permissible in narrowly defined medical emergencies. In such cases, three requirements must be fulfilled: the patient is incapable of giving consent and no lawful surrogate is available, the condition of the patient is life-threatening, or the patient is in danger of a serious impairment of health and immediate treatment is necessary to avoid this danger . The Biomedicine Convention of the European Union states When because of an emergency situation the appropriate consent cannot be obtained, any medically necessary intervention may be carried out immediately for the benefit of the health of the individual concerned. § 19 of the Health Act 2005 stipulates that if a patient who is temporarily or permanently unable to provide informed consent or is under the age of 15, is in a situation where immediate treatment is essential for his survival or long term improvement of the chances for survival or significantly improved result of treatment, a health care provider may initiate or proceed with treatment without consent from the patient or the custodian, closest relative or guardian. Details on informed consent can be found in this EU document . Information on consenting minors is provided in the literature .

In the European Union, patient rights to self-determination, safety and protection from harm are regulated and apply to all citizens , . Medical professionals acting on the basis of incomplete or invalid informed consent are considered guilty of negligence and may be subject to legal prosecution. It should be noted that the mere availability of a signed informed consent is only evidence of legal consent. Full consent requires sufficient and appropriate patient education, and, as far as possible, evidence of comprehension. In summary, a legally valid informed consent must be a clear expression of the free will of the patient. Undue influence, emotional blackmail, mock explanations and partisanship are against the law, and invalidate IC . Table 5 summarizes the steps recommended for a valid informed consent.

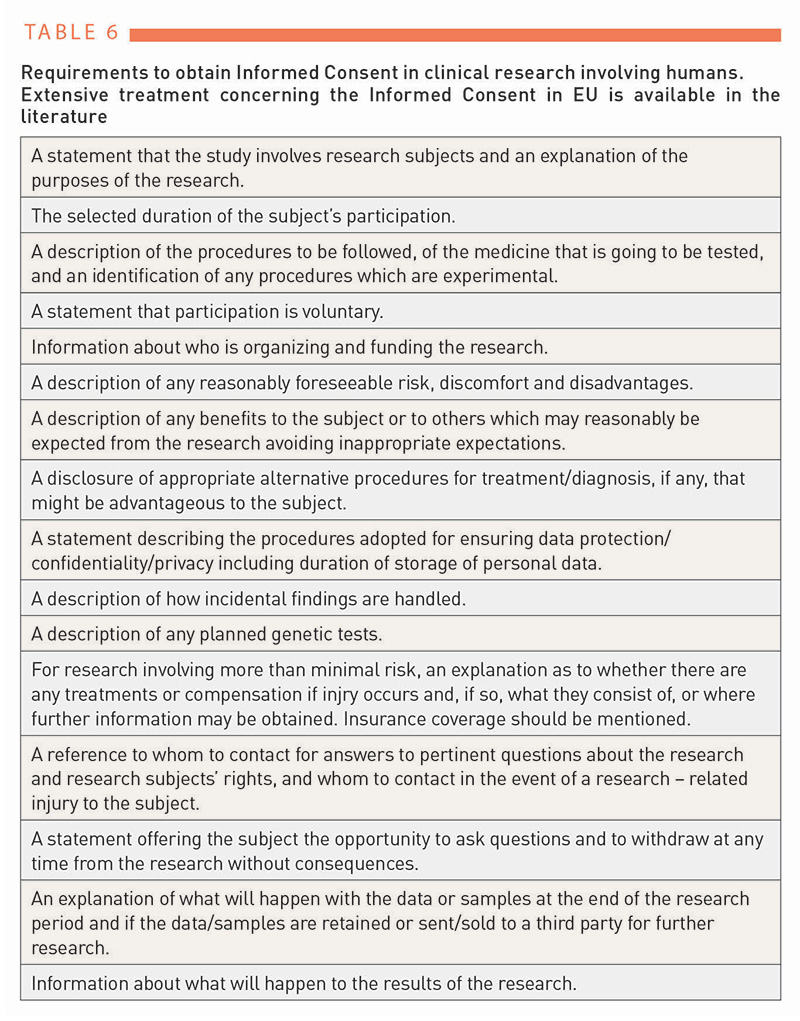

Informed consent in clinical research. The experimental nature of clinical research and past appalling experiences mandate that a complete and particularly thorough patient education is mandatory. The plan and aims of the study and all attending relevant risks must be spelled out an explained. The requirements for obtaining valid informed consent in clinical research are summarised in Table 6 .

Table 6

Informed consent in interventional cardiovascular procedures. Obtaining the consent from the patients scheduled for cardiovascular interventions follows the same principles applicable to any informed consent. Here however, four major aspects must be recognized and emphasized. Firstly, cardiovascular interventions always represent some degree of risk to the patient. Even expertly performed perfect interventions contain risk termed the optimum choice risk. Secondly, the degree and the extent of the procedural risk results from the patient-, procedure- and operator-related factors. Among these three factors the operator represents the most decisive risk factor; the same procedure carries a lower risk if performed by an expert operator compared to a less accomplished operator. Thirdly, the risk borne by the patient must be always fully and clearly stated. Fourthly, the operator must be keenly aware of the responsibility for patient’s safety. Particularly in cases of negative outcomes face-to-face with the patient and/or patient’s relatives is expected. Such face-to-face may be a humbling experience and perhaps the most important lesson in applied ethics.

The level of risk born by the patient directly or indirectly related to the operators is determined by their procedural knowledge and their cognitive and technical skills. The broad spectrum of interventional procedures implies that a single operator is unlikely to master all procedures equally. In order to minimise the risk and to maximize the patients’ safety the operators must learn to judge their level of expertise and adjust the level of risk they can responsibly and reasonably answer for, accordingly. Learning to judge one’s own competence properly is a part of a long, likely lifelong and painful learning process. The outcome of this process is an ultimate expression of operator’s accountability for patients’ safety, and therefore also ethical integrity. Operators are well advised to start assembling a library of cases with unexpected adverse outcomes. Thorough study of these cases teaches humility and in the tow consequential accountability.

Thus, patient education for endovascular procedures is intimately related to the expertise of the operator. When discussing the procedural risks the operator should preferably inform the patient about his or her own experience and expertise, rather than resorting to the statistics presented in the literature. A discussion of alternative approaches representing an important part of the education should be complete and fair. In life-threatening emergency procedures the operator may wave the consenting process based on the presumed will of the patient and on the principle of good faith. The review of risk and benefit accounting in cardiovascular interventions are reviewed in Appendix D.

Confidentiality

Confidentiality and non-maleficence are the oldest of the four main ethical principles, and autonomy is the most recent addition. Listen carefully to the Hippocratic Oath: “Whatever, in connection with my professional practice or not, in connection with it, I see or hear, in the life of men, which ought not to be spoken of abroad, I will not divulge, as reckoning that all such should be kept secret.” [Appendix B]. A patient discloses their confidences, and a physician listens and keeps them secret; this is customary in friendships.

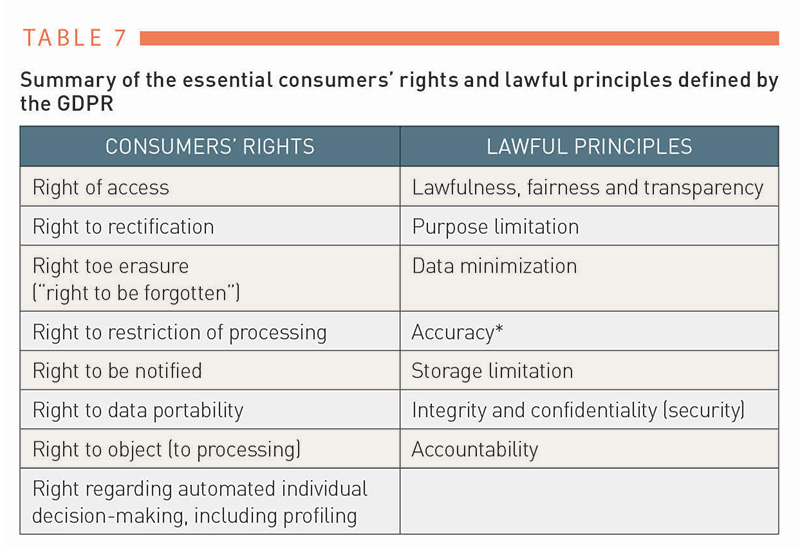

Although the physician-patient relationship has experienced profound changes since Hippocrates, confidentiality and non-maleficence remaining virtually untouched at the core. Yet, while until recently, the preservation of a patient’s privacy has depended exclusively on the discretion and taciturnity of the physician with the emergence of digital and information technologies, the risk of breaches of confidentiality, and even the risk of a patient’s personal data reaching the public domain, may be out of physician’s control representing a real threat. The evolving transformation of human-driven health care into e-Health care is associated with leagues of challenges for protection of confidentiality and safety of patients’ data. Reflecting upon this transformation the European Union has stepped up its effort to retain control over privacy and patient data by passing a series of recommendations , followed by a comprehensive regulation concerning the General Data Protection Regulation; GDPR) (Table 7) , .

Table 7

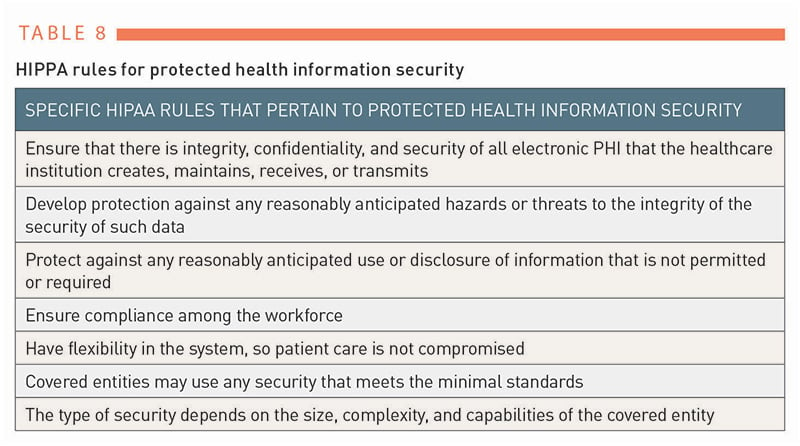

The GDPR addresses the confidentiality of all personal data, and the U.S. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) specifically protects any health information that is transmitted or maintained in electronic media [Table 8] , . Healthcare providers and organisations are now required to secure all processing of a patient’s data by establishing governance structures, including data controller teams, staff training programs, and other relevant measures.

Table 8

A physician’s principal duty of confidentiality to patient’s data and confidences remains untouched even in the eHealth era. With some exceptions, such as the protection of public health, prevention of terrorism, military or forensic enquiries, by the order of the court and so on, a physician is not allowed to share a patient’s data with anyone except someone the patient has authorised. Although the duty of confidentiality seems unequivocal in the language of the directions, there may be questions (see Illustrative Case).

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

On March 4th, 2015, Germanwings’ Airbus A 320-211 en route from Barcelona to Düsseldorf crashed into the mountains at Prads-Haute-Bleone, France: none of the 150 persons on board survived. During the investigation into the causes of the accident it was revealed that the co-pilot flying the aircraft at the time of the accident had been repeatedly ill since 2009, partly with psychotic and depressive symptoms. In December 2014 it was documented that: “the co-pilot started to show symptoms that could be consistent with a psychotic depressive episode. He consulted several doctors, including a psychiatrist on at least two occasions, who prescribed anti-depressant medication… In February 2015, a private physician diagnosed psychosomatic disorder and an anxiety disorder and referred the co-pilot to a psychotherapist and psychiatrist. On March 10, 2015, the same physician diagnosed a possible psychosis and recommended psychiatric hospital treatment. A psychiatrist prescribed anti-depressants and sleeping aid medication in February and March 2015. Neither of those health care providers informed any aviation authority, nor any other authority about the co-pilot’s mental state.” At the close of the investigation the BEA, the French authority Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety has recommended that:

EASA (European Union Aviation Safety Agency) requires that when a Class 1 medical certificate is issued to an applicant with a history of psychological/psychiatric trouble

of any sort, conditions for the follow-up of their fitness to fly

be defined. This may include restrictions on the duration of the

certificate or other operational limitations, and the need for a specific

psychiatric evaluation for subsequent revalidations or renewals.

[Recommendation FRAN -2016-011]. The lack of recommendations restricting medical confidentiality in similar cases appears surprising.

The intentional disclosure of a patient’s data as a reprehensible breach of medical ethics appears rather rare. In contrast, unintentional disclosures of a patient’s data may be more common. These offences occur largely when discussing a patient’s case with unauthorised persons such as relatives and friends, but also, for example, uploading the data onto unauthorised servers, and must be avoided. Any storage and transfer of a patient’s digital data must be explicitly authorised by the patient.

Medico-legal concepts

Physicians are generally more accustomed to dealing with professional ethics than with laws, yet, given the increasing complexity and intricacies of medical care provision, and not the last also due to widely publicised cases of medical malpractice , , physicians are well advised to get acquainted with the laws and legal regulations applicable to medicine.

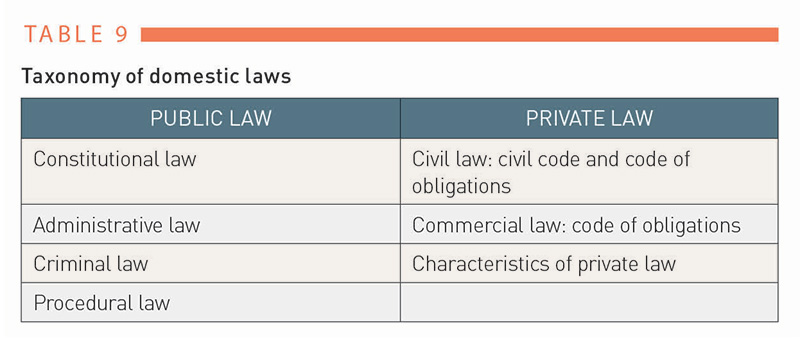

By definition, in Western countries the laws are systems of rules designed to uphold justice and order in a given country. Specific laws vary among countries, yet they are binding for all citizens in any given country, and can be enforced by the imposition of penalties. Depending on the country, different types of laws apply. Public law is a set of rules relating to the organisation and functioning of the state, and to relations between public authorities and individuals. Private law is a set of rules that govern relationships between individuals. It deals with relations between individuals, placed on an equal footing and free from any interference by public authority. These two basic types of domestic law are subdivided into several branches concerned with the specific domains of public and private life [Table 9] .

Table 9

The relationship between ethics and law is not straight forward. Historically, the ancient laws appear to define the rules of conduct of individuals, which were vital to the survival of early societies. Such early laws largely served the interests of the ruler, the ruling class, or the state. Thus, for example the Twelve Tables written in 449 BC stated the rights and duties of the Roman patrician and non-patrician (plebeian) citizens, eventually becoming the foundation of the “eternal” Roman Law . With the emerging concepts of the social contract and “justice as fairness” in the 17th and 18th centuries, formulated by philosophers such as Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), John Locke (1632-1704) and Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1773), and of utilitarianism in its various forms and traditions systematised by Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832), ethics been written into the Western laws , . The law observing ethics sets standards of conduct and penalties and ethics states the ideals of conduct.

The laws applicable to medicine deal with punishable transgressions of rules, duties and obligations, and medical ethics provide guidance for the just and fair professional conduct of health care providers. Unethical actions are not necessarily illegal (e.g. a physician passing a car accident involving human casualties without offering help), and illegal actions might not be necessarily unethical (e.g. physician-assisted suicide in countries prohibiting such assistance). The breadth of the spectrum of human relations, motifs, responsibilities, duties and other commitments and obligations explains the need for a careful and thorough evaluation of actions that become of legal and/or ethical concern. Questions related to the social plurality of moral and value concepts, and the right of self-determination, require individual considerations. Here and elsewhere, ethicists, and in legal cases lawyers, are asked to gather and evaluate facts provided by the involved parties, and weigh different stakeholder interests. ethicists do not necessarily need to draw conclusions regarding the rightness or wrongness of actions, and may provide (only) suggestions and recommendations, lawyers are expected to make judicial decisions. In most cases, recourse to the legal proceedings should be reserved for conflicts not accessible to reasoning by other means (e.g. ethics) or those representing reprehensible transgressions.

Medical law is not a specific law, rather, it borrows and applies the rules from other legal branches; articles of civil law (branch of the private law) and criminal law (part of the public law) are applicable. Tort law, a division of civil law, determines whether a person should be held legally accountable for injury to other persons.

To decide upon surmised transgressions professional standards of medical practice need to be defined. While the professional medical authorities and law makers strive to determine such standards the metrics vary and borderline cases remain difficult to decide. Thus, in gross breaches of professional conduct involving forbidden medical practices (e.g. sexual abuse of patients, billing for fictitious procedures etc.) the decisions about malpractice are straightforward. In contrast, claims of malpractice in less obvious transgressions remain often controversial.

Laws applicable to medicine differ between European countries, and consequently concerning a physician’s liability different legislations apply. The surmised transgression of medical ethics and provision of substandard medical care are frequently regulated by the responsible medical authorities according to the established professional codes. Increasingly, however, also other stakeholders in health care such as medical corporations, the pharmaceutical and medical device industries, publishers of medical scientific journals and others have established ethical codices. In minor cases admonishments apply, in more severe cases rectifying actions may involve civil or criminal prosecutions .

Claims of medical malpractice may concern any part of health care provision. Out-of-court regulations settling disputes between the involved parties, avoiding long and costly legal disputes, have become increasingly common in a number of countries. In the vast majority of cases taken to court, the civil law, largely tort law (law of non-criminal wrongdoing) deals with claims of negligence, nuisance, trespass including battery and defamation addressing the right to compensation for suffered damages. In far less frequent cases the codes of the Criminal law are applied addressing questions of gross negligence and manslaughter.

No - fault concept; medical mishaps

In out-of-court regulations the involved parties usually agree on conflict resolution either directly or by employing an independent mediator. Some countries (e.g. Sweden, New Zealand) have adopted a no-fault concept medical liability compensation system. In this system the claimant does not need to prove malpractice to receive compensation; the proof of damage related to the medical action in question (medical mishap) suffices. Arguments in favour of or against the no-fault principle have been discussed elsewhere . The no-fault concept is not legally recognised in most European countries. For example, a legal definition of the term medical mishap does not exist in German law. At present, liability insurance in health care in the majority of European countries is not designed to provide compensations in cases of damages where the causes remained unproven, an exception being the countries with a no-fault compensation principle. The issue of compensation is far from settled elsewhere, however, and remains, along with disputes about the level of financial compensation, a matter of debate with, as yet, varied court rulings.

While it is widely agreed that patient compensation is justified in cases with complications causing harm due to medical errors (unintended wrongdoing), the question of justifying a patient’s compensation in cases with unproven causality and unclear accountability remains unsettled.

Litigations

As defined by the Cambridge Dictionary the concept of liability involves someone being legally responsible for something which within the context of medicine usually means question of responsibility for harming the patient. Similarly, the Cambridge Dictionary defines litigation as the process of taking a case to a court of law so that a judgment can be made. Thus, treatments resulting from medical errors (unintentional wrong conduct) and wilful (intentional) breaches of professional medical standards may be subject to legal queries. Depending on the measure of harm to the patient, not only financial compensation but possibly also prosecution may be at stake. When culpable treatment error was proven or when treatment is conducted without a patient's consent in both instances a violation of obligations may be called based on the Civil law. Resulting rectifying actions may be ruled based on the rules of the Civil law or in severe cases based on the Criminal law. For example, treatments resulting in the death of a patient following a dubious medical intervention may result in a criminal law prosecution for gross negligence, manslaughter and offences related to ill-treatment and wilful neglect.

In legal terms, errors causing complications are considered when there a violation of the recognised rules of medical science was surmised. The recognised rules of medical science are based on medical methods that are generally known, accepted, and constantly practiced. Possible errors may occur in diagnosis and therapy and may involve actions of individual physicians but also organisational failings. The law of damages does not exempt an individual from unforeseen events. Thus, only the negative consequences of a treatment caused by breach of duty by physicians are therefore punishable in the sense of a treatment error .

Physicians accused of malpractice and involved in litigation are well-advised to provide full and honest report of their actions. However, following the legal principle nemo tenetur se ipsum accusare (no person is to be compelled to accuse themselves) such report does not expect and in most cases should not include self-incrimination. In cases of a pending litigation legal advice is strongly recommended.

Medical malpractice

Medical malpractice is defined as any act or omission, by a physician, during the treatment of a patient that deviates from the accepted norms of practice in the medical community and causes an injury to the patient. Given the vague meaning of the term “accepted norms of practice”, however, the decision about where and at which point exactly such norms have been transgressed is often difficult becoming a matter of perspective and interpretation. The issues concerning medical malpractice, if brought to a court, become subject to a specific subset of tort law that deals with professional negligence.

Medical negligence

Medical negligence is defined as improper or unskilled treatment of a patient. Internationally, the definition of medical negligence varies, and ranges from strict liability for fault, to liability for accidental damage, up to liability completely independent of fault .

Negligence as a concept of civil law addresses claims of malpractice related to the conduct of improper treatments. Claims of gross negligence are subject to criminal law. The confirmation of negligence requires three proofs; a) that an accused physician or other medical professional owed the claimant a duty of care, b) that the defendant breached that duty; and c) that the breach caused damage meriting compensation , .

According to the legal definition, any doctor acts negligently if they disregard the established and expected standards of reasonable medical care to which they are obliged and able to perform. The definition of standards of medical care is far from straight forward, however. Courts mostly define standard care as the care delivered by a reasonable doctor following the established standards of medical care, although the term experienced specialist is used in some Europeans countries instead. Nevertheless, either term implies definite performative expertise and ethical responsibility. The causality between medical action and harm inflicted onto the patient may be difficult to prove, however, or even to decide. It is then up to the court to decide whether the criteria of negligence have been met. Expert witness opinion is usually required to assist the courts in deciding on a case.

Negligence can be attested when evidence can be found that inappropriate medical actions were taken and could not be justified in a given case scenario. Once negligence has been attested, the severity of infraction and damages must also be considered. Examples of negligent (substandard) treatments include the provision of treatments without valid IC, the disclosure of confidential data, sidestepping the duty to obtain informed consent, fudging data, manipulating patient charts, and so on, Examples of gross negligence include performing high risk treatments without sufficient expertise, particularly if they result in harm or death to the patient, trafficking in drugs, covering up medical disasters, refusing emergency medical assistance, conducting unlicensed treatments, sexual abuse and so on, Allegations of negligence always require detailed and thorough evaluations; in most cases written expert opinion is required. An assessment of damages and compensation is based on considerations of fairness and reasonableness; the claims may include such damages as injuries, pain and suffering, loss of amenities, incurred expenses, loss of earnings and future losses .

When complications occur in clinical practice, negligence may be assumed or considered by the party bearing the harm. If a physician is sued for negligence, they are asked to provide a detailed account of the case; frequently, external expertise is brought in. Issues to be clarified include the availability of the required expertise and the legitimacy of the treatment, compliance with procedural standards, reasonableness of actions taken, proportionality of means and outcomes and so on. Operators are expected and should provide a full account of the procedure in question; truthful and transparent report are the best and the only defensible strategy to ensure fair and just proceedings. Legal counselling is necessary in all cases of alleged gross negligence.

Medical trespasses

Rulings upon civil (tort) or criminal law trespasses that may be relevant to health care involve direct or indirect actions against a person. Trespasses classified into separate offences such as threats, assault, battery, wounding, mayhem (or maiming), and false imprisonment are rarely encountered in health care. Threats generally involve verbal attacks on another person, and assault involves the threat or execution of actions causing the bodily harm of another person. Mobbing at work meaning the systematic pestering or bullying of another person at work may fulfil the legal definition of attack. Battery is when someone has been touched other person without consent; frequently with sexual intent (sexual battery). Such medical trespasses are failings of individual physicians and if brought to justice often attracting significant medial attention.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 70-year-old male patient is admitted with non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). Coronary angiography reveals multi-vessel coronary artery disease characterised by three high grade coronary artery stenoses in different coronary arteries. After discussing the findings, the patient agrees to proceed with percutaneous coronary intervention. The operator decides on a staged procedure and treats the most severe, partly thrombotic lesion and defers the treatment of the other lesions for later intervention. Following the treatment, the patient is transferred to the Intensive Care Unit. One hour after percutaneous coronary intervention patient experiences ventricular fibrillation and must be resuscitated. Following resuscitation, coronary angiography was repeated and revealed good result of the percutaneous coronary intervention and the occlusion of another coronary artery with a presumed non-culprit lesion on the initial coronary angiogram. The occluded coronary artery was successfully revascularised but, likely due to an extensive damage of the microcirculation, a large myocardial infarction resulted. Even in retrospective analysis it might have been difficult to decide upon the best strategy in this case.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 78-year-old female undergoes emergency carotid artery stenting (CAS) for acutely symptomatic high grade (NASCET 80%) ulcerated left internal carotid artery (LICA) stenosis. During the placement of the thromboembolic device (TED), the basket jams and cannot be released. In the attempt to overcome the resistance, the 8F Neuromax catheter becomes dislocated into the aortic arch, pulling the TED behind. The patient becomes unconscious and occlusion of the LICA and/or distal embolisation is suspected. After restoring the Neuromax catheter into the LICA, a normal cerebral angiogram is obtained and a stent is securely placed using a different TED. Following post-dilatation using 5.0x15mm balloon catheter therapy, all-out resuscitation resistant hypotension develops and the patient dies. The combination of technical difficulties (jamming device), operator error (dislocation of the catheter) and patient idiosyncrasy (resuscitation resistant hypersensitive carotid syndrome) leads to a tragic scenario with three interlinked critical factors. Retrospectively, the correct procedural actions can be easily identified; the removal and replacement of the TED with another device, no manipulation; preventing dislocation of the catheter, if possible; and indications for a carotid endarterectomy rather than CAS. A detailed and transparent review of all consequential steps will help to make future procedures safer, yet the question of the legal and ethical responsibility remains open for discussion.

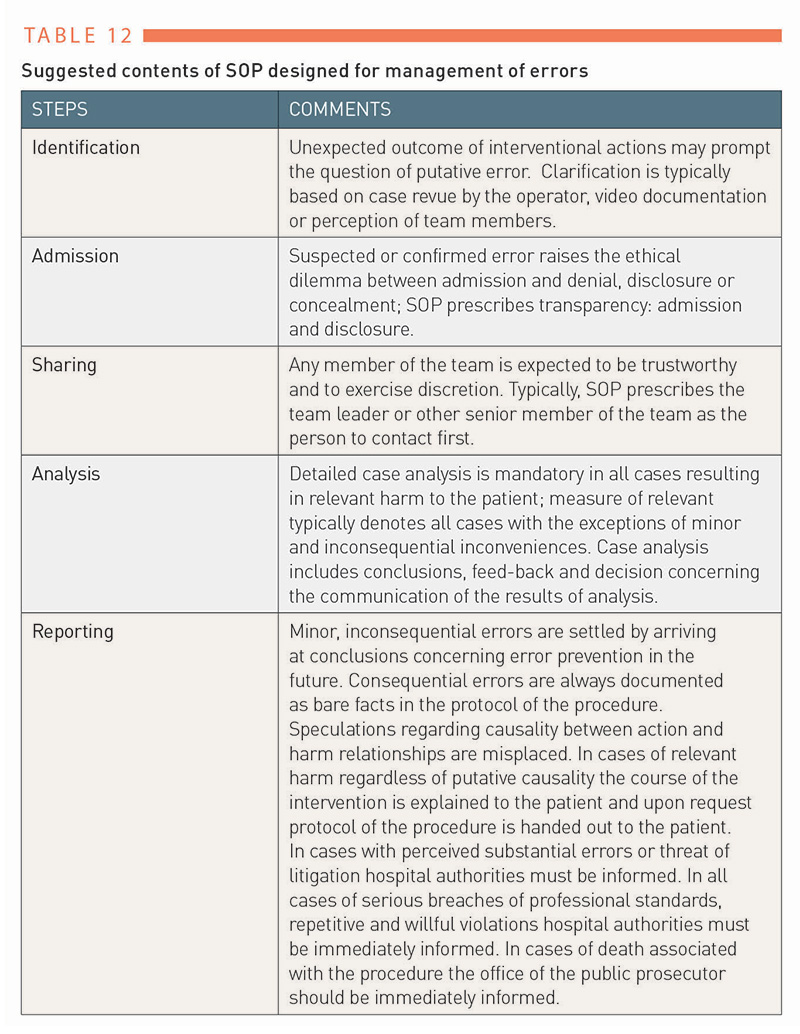

Specific ethical and legal considerations in interventional cardiovascular medicine

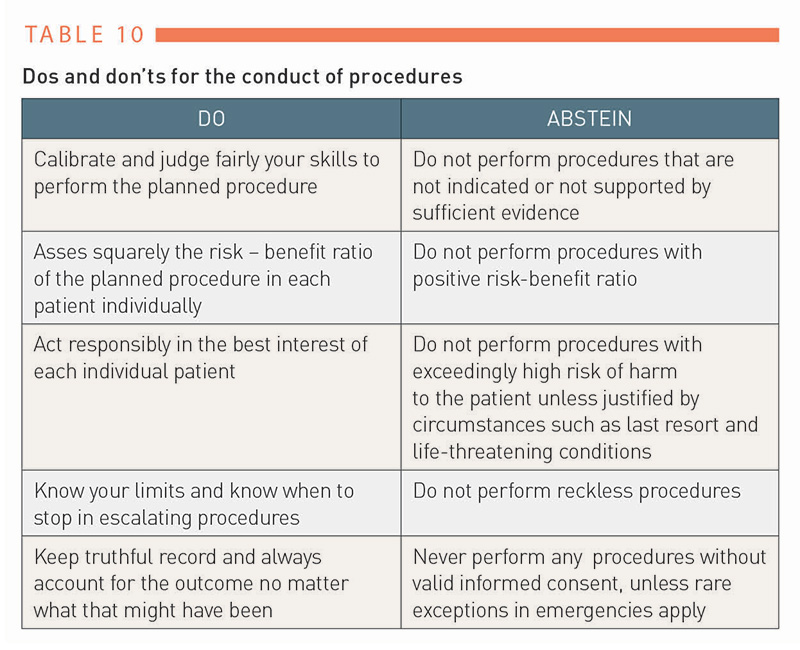

Similar to surgery, endovascular procedures may cause injury and even death of the patient. Some risks of injuries are common to all endovascular procedures, for example bleeding from the access artery, other are procedure specific, for example brain injury due to distal embolisation following mechanical thrombectomy. The operator’s first order of duty is to minimize the risk born by the patient by properly calibrating his or her skills to match the complexity of the intended intervention. The operator must be acutely aware of the fact that he or she will be always held accountable for the procedural outcome. In cases of negative outcome the first question asked is always “What went wrong”? In those cases the operator must provide plausible explanation und must understand that his or her narrative may become a subject of external and possibly even legal scrutiny. Risk accountability and ongoing risk assessment throughout the entire course of the procedure represent prime responsibility of the operators. Some of the operator’s dos and don’ts are provided in Table 10. The basic principles of risk-benefit ratio assessment are reviewed in Appendix D.

Table 10

Operator’s duty is to inform the patient about the risk of procedures; the riskier the intervention, the more comprehensive the education should be. While operators carry the overall responsibility for the conduct of procedures the liability of other parties involved (manufacturers of devices and pharmacological agents, hospital infrastructure, interdisciplinary services and so on) also need to be considered. For example, errors in handling of instrumentation need to be separated from equipment failures. However, in some cases the final ruling on responsibility for patient’s injury may remain inconclusive. In procedures deviating from the established standard due to implementation of unorthodox procedural steps or off-label use of devices, resulting in harm to the patient, the operator will be held “doubly” accountable and must be prepared to provide rational explanation for the chosen approach. It is not surprising that due to the unity of association between the conduct of endovascular procedures and risk of harm, in cases of patient’s injury the operators are more likely to be suspected of malpractice compared to the practitioners of conservative medical approaches. Consequently, the operators must learn to make prudent decisions on all treatments. If accused of malpractice openness, transparent documentation and plausibility of justifications are the best means of defence.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 90-year-old female presents with Fontaine stage IV symptoms of her left leg due to severe below-the-knee peripheral artery disease with an incomplete single vessel status with multiple critical lesions of the tibial anterior artery. Because the most critical lesion cannot be passed by any of the 0.018” or 0.014” peripheral-based instrumentation, the operator switches to a 0.014” coronary system not intended for peripheral use. The dilatation balloon passes through the tight lesion but ruptures during inflation before reaching nominal pressure. In the attempt to withdraw the device, the ruptured balloon separates from the shaft of the delivery system and remains stuck in the lesion. In a legal dispute the off-label use means that the operator will be probably ruled responsible for the complications, despite their “last ditch” effort to save the patient’s leg.

Ethical responsibilities in interventional cardiovascular medicine

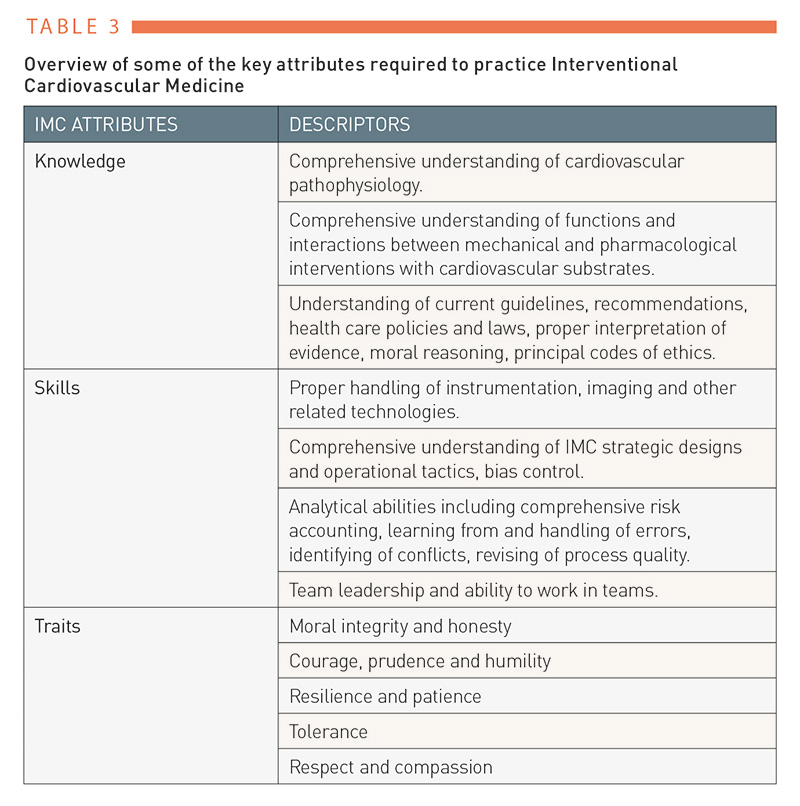

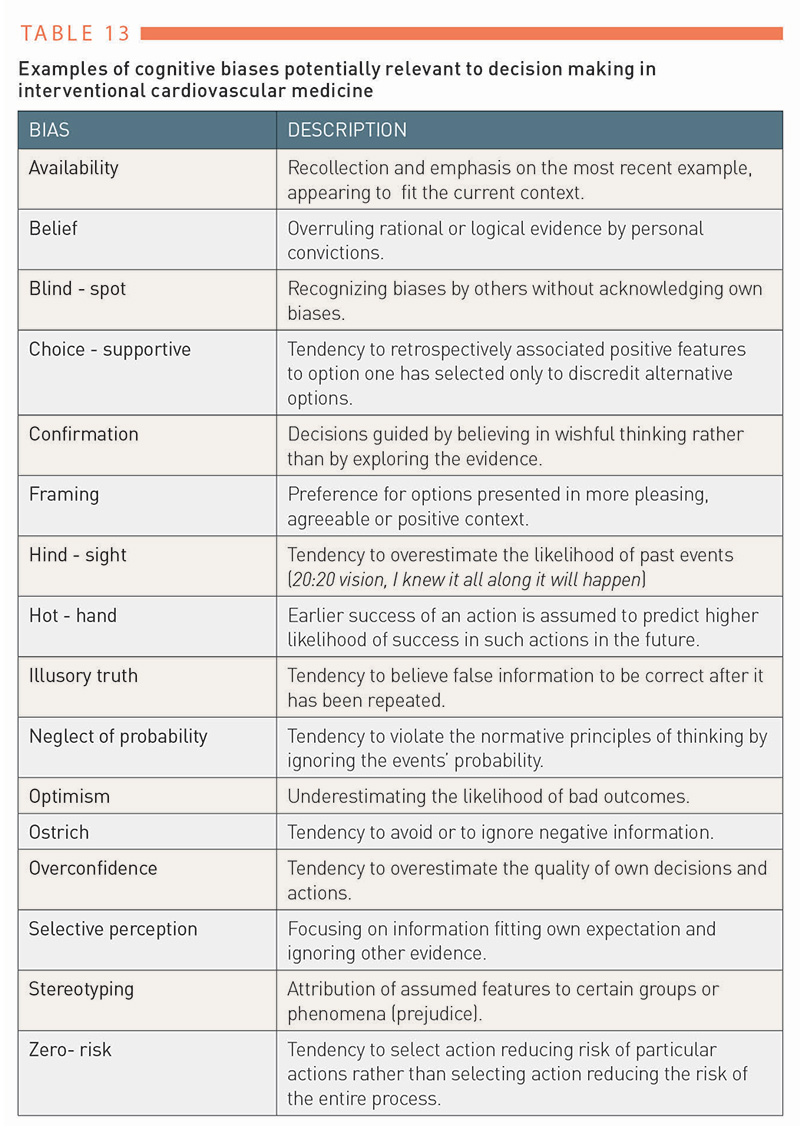

Ethics in interventional cardiovascular medicine shares the principles of biomedical ethics with some distinctions largely pertaining to the special importance and responsibility of the operators for procedural outcomes. To account for this responsibility culpably the operator must develop a number of specific “virtues”.

Virtues are considered good habits that lead people towards good actions. Health care professionals are expected to act with compassion, honesty, fairness and diligence towards patients . Beauchamp and Childress list five important virtues: compassion, discernment, trustworthiness, integrity and conscientiousness . The successful practice of interventional cardiovascular medicine however requires a number of additional specific virtues largely related to the procedural mastery, accountability and reduction of the iatrogenic risk of harm to the patient. Thus, when assessing procedural risk in individual patients the operator must be keenly aware of, and account for, the probabilistic nature of the risk assessments related to the differences in individual skill levels, possibly imperfect visualisation of the target sites, limited manual control of the instrumentation in difficult anatomy, potentially unpredictable responses of tissues to mechanical actions and so on. Furthermore, operators frequently exposed to emergency cases often associated with life-threatening events, frequent dealings with lengthy, mentally and physically demanding procedures requiring stamina and emotional stability, practice in a competitive high-pressure environment and so on, need to be prepared to deal effectively with all these and other challenging factors as they come along. Successful mastery of such unique and challenging terrain requires acquisition of specific “virtues” some of them discussed below.

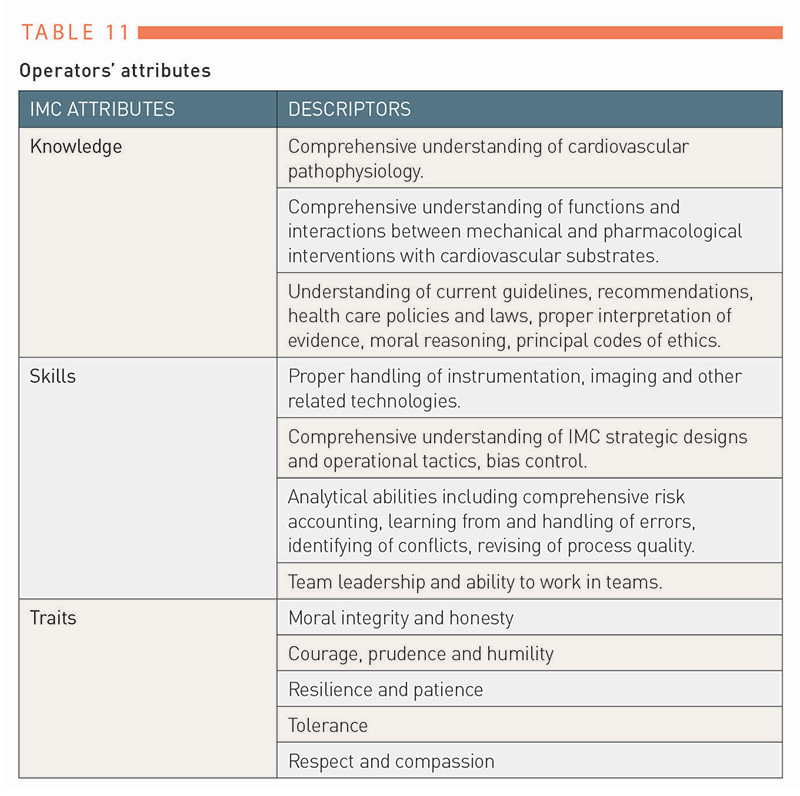

Attributes and virtues of operators

Operators are naturally fully responsible for the patient’s safety and well-being. This noble responsibility is based on individual technical and cognitive expertise and ethical integrity. Some of the operator’s professional attributes are captured in Table 11.

Table 11

Teaching of the required operator’s professional attributes is based on explicit learning from textbooks, lectures, conferences, live-case demonstrations, virtual and simulation devices, and clinical practice , . In contrast, learning of ethics is largely implicit and tacit. This is definitely not enough. Here the attempt is made to explicate some of the ethical “virtues” and attributes complementing operator’s cognitive and technical expertise.

Professionalism and professional honesty

Professions are known as occupations requiring specialised qualifications and expertise. Thus, professionals apply specialised knowledge and/or technical skills in service to the community. In order to justify professional services, communities decide on their importance, acceptable costs and the privileges granted. In return, professional bodies take care for the provision of the agreed upon services. To assure the quality of services professional standards of conduct and guidelines, and in the case of medicine, moral responsibilities, are established . Professional honesty is such a case in point.

Honesty is one of the moral maxims, and means truthfulness. However, absolute transparency and unrestricted openness characterize an ideal state not reached in the real-life context. Furthermore, in the Western interpretation of medical ethics question of honesty remains a controversial subject . While doctors should not lie to or for the patient, there are certain circumstances where less than full disclosure and resort to white lies may be justified. Albeit the full disclosure represents the preferable approach in most cases, context-specific decisions about the degree of disclosure may apply depending on the wisdom and the discretion of the physician and the presumed or explicit best interest indicated by the patient. If a decision was reached to restrict disclosure, such a decision must be based on ethically defensible principles.

The benefits and harms of a full disclosure of the truth in clinical practice have been discussed in the literature from both the patient and operator perspectives, but remain inconclusive. Issues of concern regarding a physician’s full disclosure include mainly three factors. Firstly, the full disclosure of an error could imply prosecution for bodily injury or manslaughter due to negligence. Secondly, the law follows the maxim that no one is bound to incriminate him or herself. Thirdly, financial and capital responsibilities remain incompletely defined . In clinical practice in cases resulting with patient’s injury or death, and particularly with threat of litigation, full disclosure is morally and legally the best, if not the only, option. Attempts to cover up or lie in such cases are likely not only to undermine or even to destroy physician’s ethical integrity, but also augur troubles in the pending and possibly also future proceedings.

In the illustrative case of the 70 years old female patient, the operator applied a policy of incomplete disclosure. Was the operator obliged to disclose the full technical details of the procedure to the patient? Was the patient entitled to full disclosure? Does the policy of don’t ask don’t tell apply? What should the answer have been, if the patient were to directly ask about the technical details? Would full technical disclosure have been imperative in the case of legal proceedings, or of the patient’s death?

Possible and tentative answers in this case take into account four propositions. Firstly, the operator is not principally obliged to provide full disclosure. Secondly, if not directly asked by the patient, then apart from lying, the specific description of the course of the procedure remains at the discretion of the operator. Thirdly, the operator is principally obliged to provide full disclosure, if questioned by legal authority. Fourthly, if directly asked by the patient then the operator should disclose the truthful course of the procedure, but explanations of possible causality between the procedural actions and procedural outcomes should be avoided.

In order to develop and sustain ethical integrity, operators should develop a firm sense of accountability and full responsibility for their actions at all times. Avoiding or evading responsibility, belittling potentially avoidable complications, dishonesty and the denial of failures is, if not in the short-term, definitely in the long term, a recipe for disaster, while in contrast, habitual professional accountability is a safe harbour.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 70-year-old female presented with a left hemispheric ischemic stroke and high-grade stenosis of the left internal carotid artery (LICA) by colour duplex ultrasound examination. Following clinical stabilisation, extensive patient education and after signing informed consent papers, the patient was scheduled for elective carotid artery stenting (CAS). Four-vessel cerebral angiography revealed NASCET 95% stenosis of the LICA and a heavily calcified type III arch as the main findings. Despite multiple attempts using various combinations of different guiding catheters and 0.035” guidewires, the sheath could not be introduced into the common carotid artery (CCA). At this point the operator decided to employ the 8F Simmons II catheter. The attempts to reform the catheter in the aortic root failed. Multiple failures prompted the operator to attempt the reformation of the catheter by placing the stiff end of the guidewire first. Suddenly, the patient experienced severe chest pain. Angiography of the aorta revealed focal dissection of the ascending aorta. The patient was transferred to cardiac surgery for aortic repair. The post-operative course was uneventful. Following recovery, the patient was informed that emergency surgery was required to treat CAS-related complications; the presumed cause of the complications was not stated.

The likely cause of the aortic dissection complicating the CAS procedure was the use of the stiff end of the 0.035” guidewire inside the vascular system; this was clearly a breach of interventional rules. The operator reported that in this case the use was deliberate. The operator said that the reason for resorting to this approach was their worry about the increasing risk of stroke complication and frustration about the course of the lengthy and difficult procedure. The operator said that it was the first time the approach had been implemented. The operator said that the choice of other technical options or referring the patient to surgery was not considered at the time.

The intervention resulted in serious harm to the patient. The reason for the aortic dissection is probable but not definitely proven.

Solecism, Corruption and Transparency

Solecism is derived from Soli, the name of an ancient Athenian colony where a dialect regarded as substandard was spoken , and originally meant deviations from the rules of grammar. In a wider sense solecism means deviations from accepted standards. In the domain of public services, including health care, the prime example of solecism is corruption. Transparency International, which is representing a global movement to stop corruption and promote transparency, accountability and integrity at all levels and across all sectors of society defines corruption as the abuse of entrusted power for private gain, and as coming in a number of guises; opaqueness, bribery, clientelism, collusion, conflict of interests, false disclosure, embezzlement, lobbying and patronage are only some . Corruption in medicine frequently concerns the intrusion of illegitimate, and at times hidden, pecuniary interests of stakeholders. The moral corruption of health care providers negates duties and obligations towards patients. The single most reliable counter-measure to corruption is transparency. The Cambridge Dictionary defines transparency as the quality of being done in an open way without secrets . In the context of health care, transparency thus means two things: firstly, the full disclosure of interests and decisions about their legitimacy, and secondly, appropriate behaviour in health care provision by responsible authorities.

Rare cases of a doctor’s corruption have surfaced from time to time in the past, and caught the public’s attention. In the vast majority of such cases based on the principles of self-governance, rectifying disciplinary measures were implemented by responsible professional authorities. More recently, however, the number of cases has risen, and grave transgressions, including gross breaches of the medical professional codex, seemed to have increased.