Secondary coronary revascularisation

Summary

The need for secondary coronary revascularisation is growing worldwide. Given the chronic nature of atherosclerotic disease, in conjunction with an ageing population, many patients with cardiovascular disease will undergo crossed surgical and percutaneous coronary interventions during their lifetime. Patients requiring repeat coronary interventions typically fall into higher risk categories and have multiple comorbidities including diabetes, chronic renal failure and peripheral vascular disease. High atherosclerotic burden in native coronaries, saphenous graft attrition and stent failure contribute to the increased risk and complexity faced in this challenging clinical subset. This chapter addresses the crossed modalities of secondary revascularisation. Attention is paid to percutaneous intervention of surgical conduits and native vessels in patients with prior surgical coronary revascularisation. The application of crossed intervention in the management of acute percutaneous and graft failure is also discussed. The authors stress the importance of the heart team for decision making in secondary revascularisation and insist on the importance of avoiding ad hoc, episodic care in this challenging group of patients.

Secondary coronary revascularisation

The possibility that an individual cardiovascular patient will require more than one coronary intervention has increased substantially over the last two decades due to several factors With an ever growing elderly population, this increases not only the number of cardiovascular patients, but also the possibility of disease progression or surgical graft failure in those with previous coronary revascularisation. The prospect of undergoing secondary revascularisation is influenced by patient age, with younger patients being more likely than older ones to undergo repeat procedures. Incomplete revascularisation, for example resulting from a “culprit stenosis only” strategy in acute coronary syndromes, causes more repeat coronary interventions in the long term. Paradoxically, the absolute figure of repeated revascularizations for restenosis has increased in the DES era as a result of the growing number of patients treated with PCI. Finally, the accessibility to coronary revascularisation has increased over the last 20 years, largely due to the creation of new catheter laboratories, but also due to the development of new surgical units or to an increase in the activity of pre-existing ones.

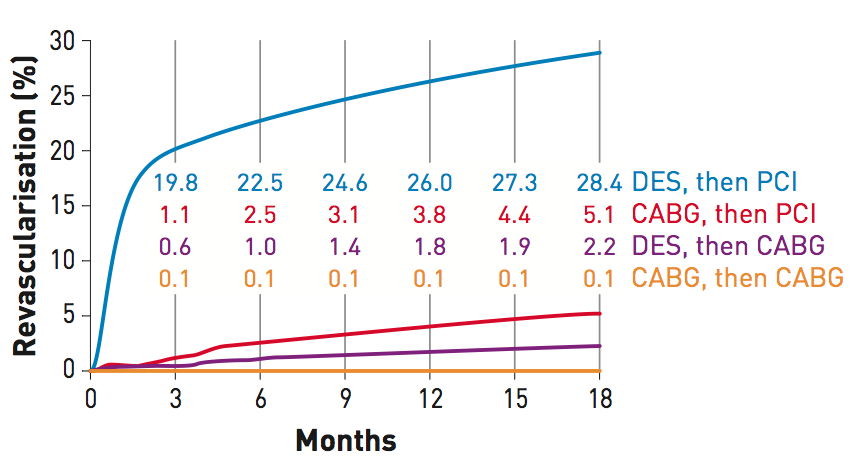

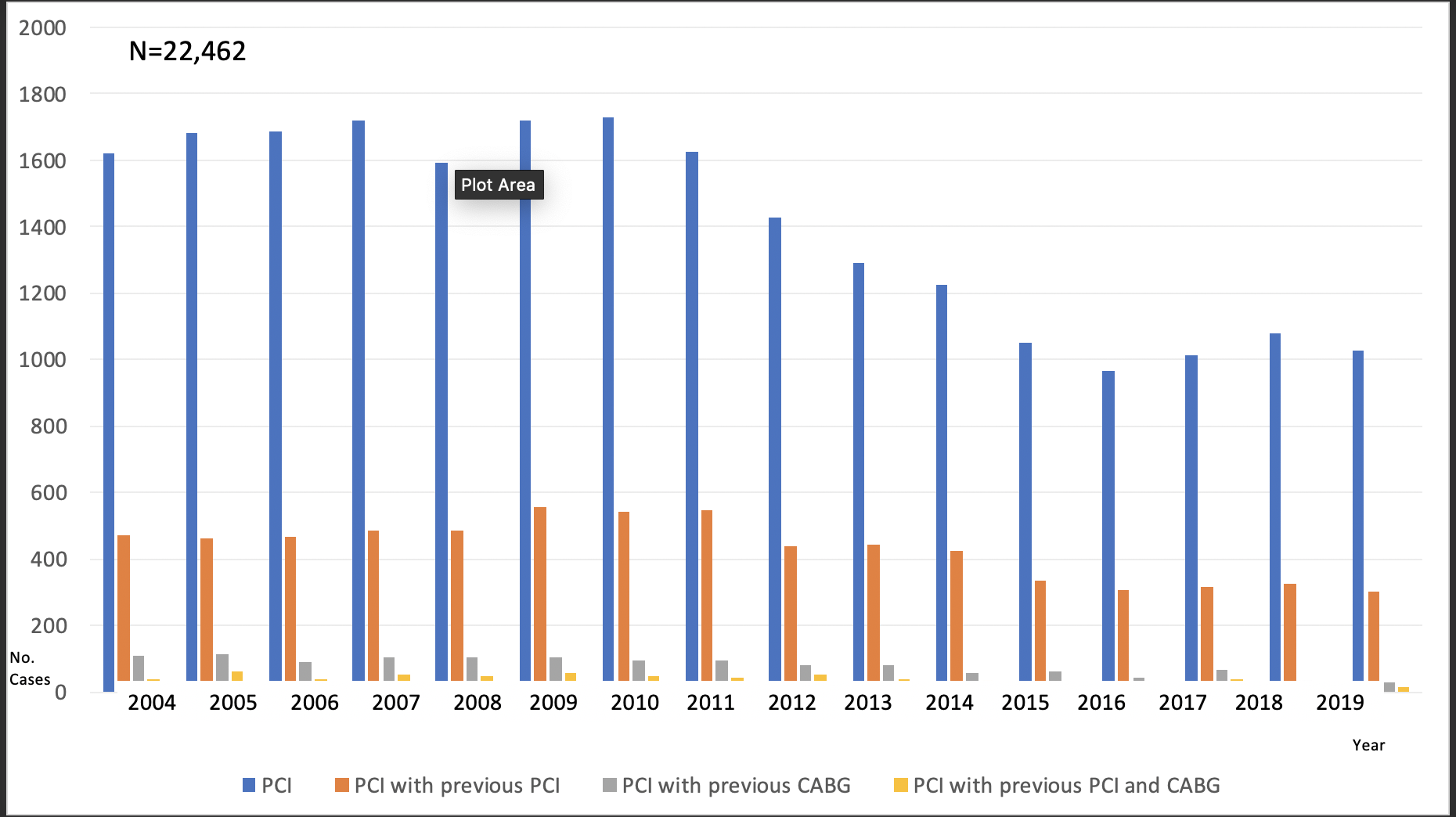

There is limited available data on current secondary coronary revascularisation rates. Data from the European Heart Survey on coronary revascularisation collected on 7,769 patients in 2001-2 revealed that of the 4,442 patients under-going surgical or percutaneous revascularisation, 14% had a previous history of CABG and 34% of PCI . Information obtained from the New York State registry already in the DES era (2003-2005), revealed an overall re-intervention rate of 36% within the first month after coronary interventions (Figure 1), with most cases being repeat PCI procedures after a DES implantation (28%). A review of 6362 PCI procedures performed at the Hospital Clinico San Carlos in Madrid between 2014 and 2019, revealed that the percentage of patients with prior interventions (surgical or percutaneous) undergoing PCI has remained relatively stable, constituting around 35% of total PCI procedures New Figure 2 . This is in spite of the tremendous overall increase in PCI procedures which has taken place over the last three decades and reflects both the increased demand and the inclusion of new expanded indications of PCI (multivessel disease, acute myocardial infarction, etc.)

Figure 1

Rates of secondary coronary revascularisation within 18 months after surgical (CABG, n=7,437) or percutaneous (PCI, n=9,963) primary coronary interventions in New York State between 2003 and 2004. Data corresponding to the 4 different modalities of secondary revascularisation is shown in different curves. By far, the most frequent modality of secondary revascularisation during this period was PCI after initial percutaneous revascularisation. This was followed by PCI after initial CABG.

[From Hannan et al with permission]

Figure 2

Trends in percutaneous revascularisation

Institutional trends in percutaneous revascularisation, as reflected by 22,426 percutaneous revascularisation (PCI) procedures performed at a European centre (Hospital Clinico San Carlos) between 1985 and 2009. The approximate date when relevant developments in PCI were introduced is displayed below the graphic. The percentage of patients with prior interventions (surgical or percutaneous) undergoing PCI remains pretty stable since 1990, being 34% within the last 4 years. The last lustrum is incomplete, and only a 4-year period is shown (hence the arrows predicting figures by the 5th year). POBA: plain old balloon angioplasty; BMS: bare metal stents; EPD: embolic protection devices; DES: drug eluting stents; AD: aspiration devices.

[From Escaned J with permission]

The term secondary revascularisation emerged in response to the lack of a recognisable category grouping for all of the available knowledge on different aspects of diagnostic and therapeutic management of patients undergoing repeat coronary interventions, . When formulating bibliographic search strategies for this topic, it quickly becomes evident how scattered the current available knowledge is. Thus, a systematic review requires the use of multiple terms such as “re-operative”, “redo”, “repeat”, “bypass”, “restenosis”, etc., to name but a few. This absence of clear terminology mirrors the frequently observed polarisation of synergy between surgical and interventional teams. However, as will become evident in the course of this chapter, the challenges posed by secondary revascularisation makes it imperative that decisions are taken in the context of an integrated heart team involving both cardiac surgeons and interventional and clinical cardiologists. Secondary revascularisation includes all interventions following an index procedure (PCI or CABG) whether or not this relates to the original lesion or arterial territory. Crossed secondary revascularisation refers only to those revascularisation procedures with a different modality than the first one; therefore, two main scenarios are possible: 1) PCI in patients with prior CABG, and 2) CABG in patients with prior PCI.

Patients requiring secondary revascularisation procedures frequently present more cardiovascular risk factors which trigger aggressive atherosclerosis, . At a systemic level this translates to a higher prevalence of extracardiac complications such as renal insufficiency and stroke, and at a cardiac level to more frequent episodes of infarction and lower left ventricle ejection fraction. These patients may also present a larger atherosclerotic burden in their coronary vessels which results from, among other causes, disease progression during the time which has elapsed since the first intervention, leaving fewer options for surgical and percutaneous re-interventions , . Long-term failure of the primary revascularisation may be linked to suboptimal procedural results in the context of extensive, diffuse atherosclerosis. Small vessel calibre and vessel calcification, for example, are at the same time determined by the presence of cardiovascular risk factors, and are also important determinants of optimal stent expansion and performance of adequate anastomoses of surgical grafts.

The following paragraphs will discuss different aspects of crossed secondary revascularization on patients with previous CABG or PCI (a detailed discussion of repeat percutaneous coronary intervention on in-stent restenosis or stent thrombosis can be found in In-stent restenosis). A critical issue is to choose the most appropriate modality of re-intervention. Relevant clinical practice guidelines have barely covered this issue. The 2009 Appropriateness Criteria for Coronary Revascularisation document endorsed by several American scientific societies, which has been updated most recently in 2017,– included a discussion of secondary revascularisation in patients with previous CABG. More recently, the ESC guidelines on myocardial revascularisation have dedicated a more specific section to discuss the problem of repeat revascularisation. Detailed information on the recommendations laid out in this document will be provided in various sections of this chapter. The reader will have the opportunity to confirm that the level of evidence in many of these expert recommendations is C, meaning that little evidence could be found in the literature to support expert opinions. There are several contributory factors to this void of evidence, but an important one is that patients with prior CABG have been systematically excluded in RCT comparing primary CABG and PCI in multivessel disease, and therefore no information on this subgroup is available.

Secondary revascularisation in patients with prior CABG

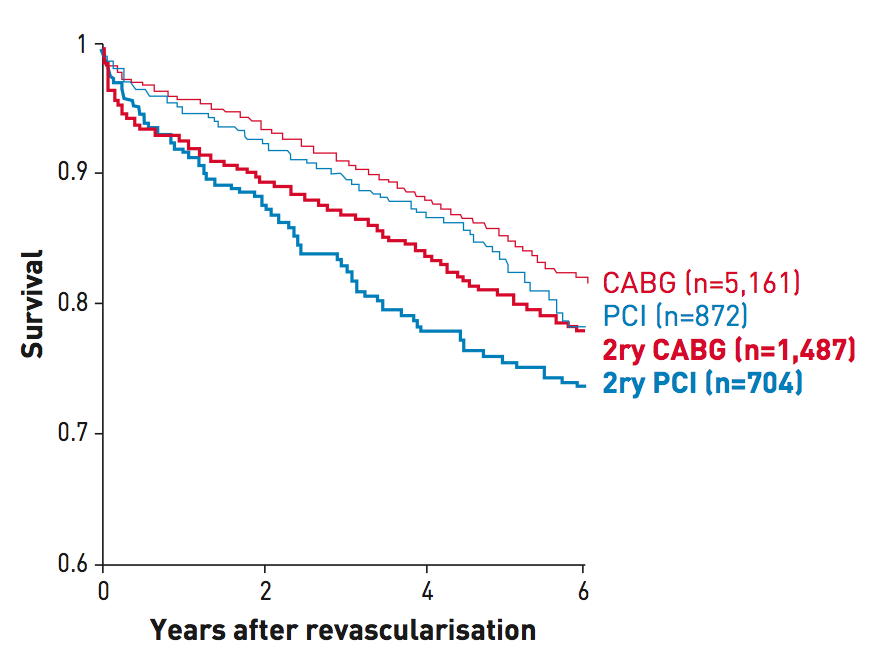

Previous CABG is a frequent context for secondary revascularisation, increasing dramatically in the second decade after CABG, , The attitude towards the modality of repeat revascularisation in patents with prior CABG has shifted over the last 20 years. Redo coronary surgery boomed in the eighties, and was followed by a more conservative and critical attitude with a decrease in the number of surgical re-interventions and was eventually superseded by crossed revascularisation with PCI. About 3% of patients with prior CABG undergo re-do CABG . The most recent ESC Guidelines on Myocardial-Revascularisation published in 2018 recommend PCI as the first choice for repeat revascularisation if technically feasible rather than re-do surgery in patients with previous CABG (class IIa, level of evidence C) . Retrospective studies have demonstrated that both PCI and CABG have a significantly higher risk in this context than in first revascularisation. Compared with de novo multivessel revascularisation, 5-year mortality has been found to be virtually twice as high in patients undergoing secondary revascularisation, either percutaneous (25% vs. 16%) or surgical (21% vs. 14%)–(Figure 3). Surgical series consistently identified re-do CABG as a predictor of risk in coronary artery surgery, , particularly for early postoperative outcomes, with a higher in-hospital mortality, myocardial infarction (MI) and prolonged ventilation. Such outcomes are associated with an increased complexity and risk derived from sternal re-entry, pericardial adhesions, patent internal mammary artery (IMA) and patent but diseased saphenous vein grafts (SVG). Cumulative advances in perioperative management, such as minimally invasive incisions, new modalities of myocardial protection and off-pump intervention, have however, contributed to a decrease in the risk of re-do CABG. It remains to be seen whether other novel surgical techniques, such as external stenting of SVG, developed to improve the long-term patency of SVG based on its potential to maintain the graft lumen uniformity and improve shear stress, will reduce the need for re-do CABG, .

Figure 3

Unadjusted survival curves from PCI and CABG cohorts after primary multivessel revascularisation (CABG and PCI, thin lines) and secondary revascularisation (reCABG and rePCI, thicker lines) from a large volume centre, showing the poorer outcome of patients undergoing secondary revascularisation, irrespective of the technique used. The graphic has been built by merging data from two separate reports from the same institution (Brener SJ et al. Circulation. 2004;109:2290-5 and Brener SJ et al. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:413-8.). The number of patients included in each cohort is shown between brackets. 2ry: secondary revascularisation.

[From Escaned J with permission]

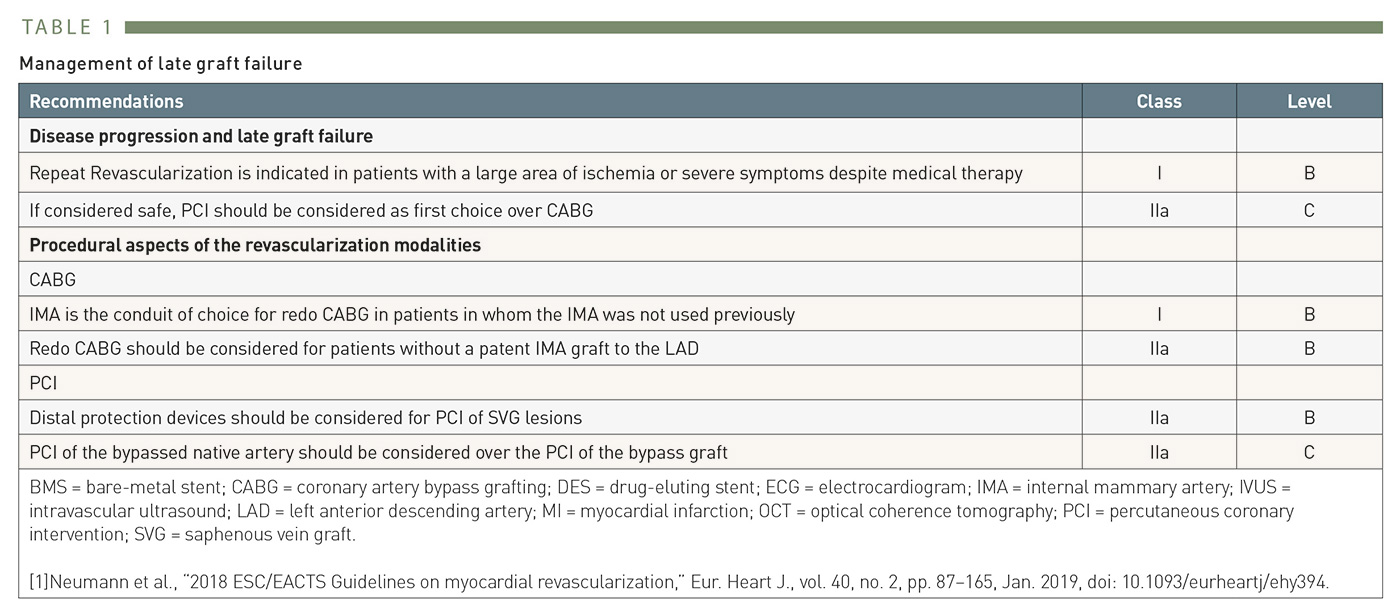

Decision making on the modality of secondary revascularisation in patients with prior CABG appears to be influenced by a number of anatomical and clinical features. Surgical re-intervention is preferred over PCI in patients at higher risk, with fewer functional grafts, more chronic total occlusions (CTO), and lower systolic function. Conversely, PCI is the technique of choice in patients with patent IMA and a suitable coronary anatomy. However, the benefit of choosing any of these modalities appears to be limited, since prognosis is mostly affected by age and left ventricle ejection fraction. Moreover, it seems that in patients with patent IMA to left anterior descending artery (LAD) presenting with ischaemia in remote myocardial territories, re-intervention -CABG or PCI- of such territories may relieve symptoms but not improve the survival. However, it has been demonstrated that both physicians and patients influence the modality of secondary revascularisation after CABG. In the registry of the AWESOME (Angina With Extremely Serious Operative Mortality Evaluation) trial, to date the only RCT dedicated to secondary revascularisation after CABG, the study’s physicians and patients opted for PCI by a 2:1 margin over re-do CABG. A similar trend in the referral of CABG patients to secondary treatment with PCI can also be observed in data obtained in New York State. Crossover between surgical and percutaneous modalities in re-intervened patients occurred in 7% of patients: the prospects of undergoing PCI as a secondary procedure after surgery was more than twofold that of having CABG as a re-intervention after PCI. In the prior mentioned AWESOME study, patients with previous CABG presenting with refractory ischaemia symptoms that underwent re-do CABG had a higher in-hospital death rates compared with patients that underwent PCI. However, long-term survival (3 year follow-up) was similar between both groups. Those results regarding long-term outcomes have been confirmed in other observational study in which clinical outcomes (median follow-up of 4 years) were similar in both re-PCI and re-do CABG in patients with graft failure . A secondary analysis from the EXCEL(Everolimus- eluting stents or bypass surgery for left main coronary artery disease) trial sought to assess the incidence, risk factors, and prognostic impact of the performance of repeat revascularization procedures following PCI or CABG at three years.This study found that index PCI of the left main stem was associated with higher rates of any repeat revascularisation compared with index CABG. Importantly, the need for repeat revascularisation was associated with increased risk for all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality regardless of the index revascularization approach (PCI or CABG). Furthermore, mortality was significantly greater after repeat revascularization by CABG but not after PCI, reflecting inherent differences in the risks of these 2 strategies. This observation suggests that CABG should be reserved for repeat revascularization procedures that are not amenable to repeat PCI, irrespective of the initial revascularization approach These results have proposed PCI as the preferred strategy of re-intervention in patients with patent IMA and favourable anatomy . The recommendations for treatment of late CABG failure collected in the 2018 ESC guidelines on myocardial revascularisation are shown in Table 1.

Table 1

2014 ESC Guidelines recommendations for secondary revascularisation after late CABG failure

New modalities of percutaneous intervention provide solutions for the anatomical challenges posed by the long, tortuous vascular circuits created by surgical grafting of the coronary arteries. As an example, magnetic navigation has been used in complex PCI of patients with prior CABG and other complex scenarios, Figure 4). Regarding re-do CABG, left internal mammary artery (IMA) graft continues to show the best clinical outcomes in patients who did not receive a LIMA during their first CABG; In fact, clinical guidelines recommend IMA as the conduit of choice for re-do CABG if available, with a class I, level of evidence B . Redo CABG should also be considered in patients without a patent IMA graft to the LAD, class IIa/B.In those patients with prior IMA graft, radial artery seems to have better outcomes at long-term in re-do CABG compared with SVG.

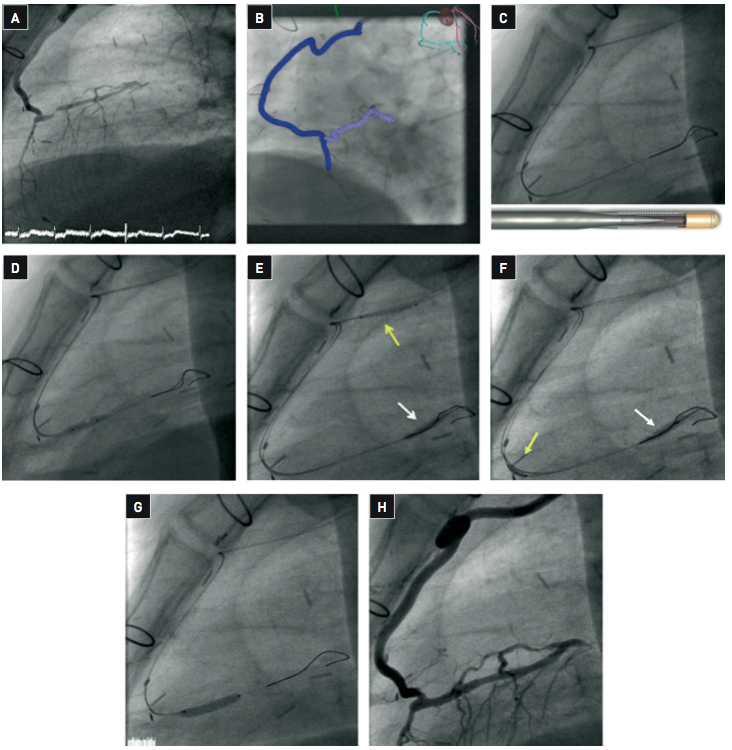

Figure 4

(A) TheLAD was occluded in its proximal segment. The patient presented chronic renal failure with creatinine clearance of 45 ml/min. (B) The procedure was performed using magnetic navigation (Stererotaxis) in order to facilitate guidewire advancement through this complex anatomy and reducing contrast administration to a minimum. A Constellation 3D vessel reconstruction was performed to modulate the magnetic field during the procedure. (C) Two magnet-tipped Pegasus guidewires (shown in the lower part of the illustration) were advanced using the 3D vessel reconstruction and magnetic navigation. The second magnet-tipped Pegasus guidewire was used to perform a reverse trapping technique. Using a Terumo Finecross® microcatheter, one of then Pegasus guidewire was exchanged for a Asahi GrandSlam guidewire. (D) Balloon dilation was then performed. (E-F) The balloon was then further advanced upstream and inflated to trap the second Pegasus guidewire (white arrow) and a Biosensor BioMatrix™ 2.5x12 mm stent (yellow arrow) was then advanced over the trapped guidewire. This allowed successful positioning of the prosthesis at the stenotic site. (G) Withdrawal of the GrandSlam guidewire was then performed over a microcatheter (white arrows) to prevent damage of the sharp vessel bends by the guidewire, and the stent was deployed. (H) An excellent angiographic result was obtained. The total amount of contrast medium used in the procedure was 93 ml. The patient evolved favourably without evidence of contrast-induced nephropathy.

[Case courtesy of Javier Escaned, Hospital Clinico San Carlos, Madrid, Spain]

PCI IN SAPHENOUS VEIN GRAFTS

Treatment of SVG stenoses is a common scenario for PCI after CABG. This is due to the fact that SVG attrition is a time-related phenomenon, with a graft patency at 10-15 years of 25% to 50%, , . Intimal hypertrophy and atherosclerosis are contributing factors to long-term failure of SVG. The thin wall of the venous graft is exposed to systemic arterial pressure, which contributes to the atherosclerotic degeneration process. Intracoronary imaging has been key to detect early abnormalities of the SVG walls, as thin-cap fibroatheroma, fibrous neointima and adherent thrombus, that may contribute to the risk of future occlusion.

Percutaneous interventions in SVG are fraught with a number of potential complications. In the first place, SVG have a thinner wall than coronary arteries, and therefore they are more prone to rupture as a result of over-dilatation, , . Under-expansion of deployed stents has to be dealt with carefully, given the risk of venous graft rupture (Figure 5). Heterogeneous plaque composition, with coexistent calcified and soft plaque areas may increase the risk of SVG rupture during dilatation. Contrary to popular belief, pericardial tamponade may occur after vessel or graft perforation in patients with prior pericardiectomy . It is important to stress that patients with prior CABG undergoing PCI of SVG failure are at high risk for cardiac events. A very large observational study has found high rates of clinical outcomes at 3 years follow-up in patients older than 65 subjected to PCI of SVG failure (death 24.5%; MI 14.6%; urgent revascularisation 29.5%).

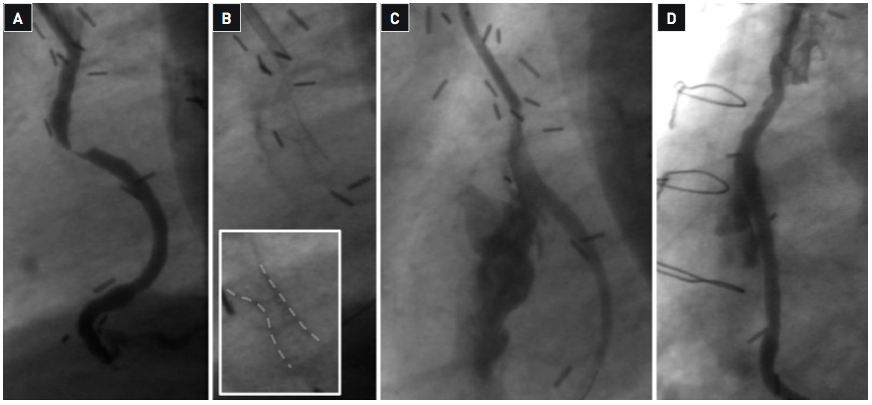

Figure 5

(A) The targetstenosis was located around 30 mm from the aortic anastomosis. (B) Bare metal stent implantation was performed after balloon predilation, but incomplete stent expansion persisted at 18 Atm inflation pressure. (C) High pressure postdilation with a non-compliant balloon was performed beyond 20 Atm. The relief of the stent narrowing was immediately followed by massive extravasation of contrast, indicating graft rupture. (D) The balloon was kept inflated in place to stop bleeding while a second guiding catheter was inserted through the contralateral femoral artery. After crossing with a second guidewire a JoStent PTFE covered graft stent was advanced and successfully implanted at the site of the rupture. The image shows the final result with contrast retention in the haematoma around the graft but with no active bleeding.

[Case courtesy of Camino Bañuelos and Rosana Hernández, Hospital Clinico San Carlos, Madrid, Spain]

A more frequent cause of complications of SVG PCI is atheroembolism. Vein graft attrition is caused by an accelerated form of atherosclerosis, friable tissue and the atheroma in these vessels are more prone to dislodgement by intracoronary devices than in native coronary atheroma. There is a relationship between some characteristics of the treated SVG and the risk of complication during PCI. In the AMEthyst trial, a study comparing the efficacy and safety of the AVE Interceptor embolic protection device (EPD) with the GuardWire ® (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) or FilterWire EPDs, the univariate predictors of MACE at 30 days included plaque volume, target lesion length, vein graft degeneration score, coronary narrowing classification, reference vessel diameter, and male gender, and was independent of device type. However, plaque volume was the most important and the only multivariate predictor of MACE in that study.

The introduction of EPDs constituted a major breakthrough in SVG PCI. A detailed discussion of EPD can be found in Thrombectomy and target vessel protection during PCI . Despite the 2014 ESC clinical practice guidelines initially recommending the use of distal EPD in SVG PCI with I/B class/level of evidence, data concerning the benefit of EPD in terms of long-term outcomes and procedural success have been found to be controversial in a number of recent and very large observational studies, . Therefore, the recently updated ESC 2018 Myocardial revascularisation guidelines have downgraded the recommended use of distal protection devices in SVG-PCI procedures to a IIA/B class/level of evidence . In addition, it is important to highlight that the use of EPD in real life is far from being universal , , . This suboptimal usage of EPD in SVG PCI cannot be justified by technical problems such as the presence of small vessel diameter or aorto-ostial location, since current technology makes possible both proximal and distal SVG protection.

Other techniques have been tested or proposed to prevent atheroembolisim during SVG treatment. Covered stents have been used in SVG on the grounds of improved scaffolding characteristics. Two covered stents have been compared with BMS in randomised clinical trials. The JoMed polytetrafluor-oethylene (PTFE) covered stainless steel stent (JoMed, Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was tested in 3 trials (RECOVERS, STING and BARRICADE) , , enrolling a total of 755 patients in SVG . The results were unfavourable in terms of 30 day MACE (RECOVERS), and restenosis and MI (STING). Moreover, PTFE was inferior to BMS regarding target vessel failure after 5 year follow-up of patients included in BARRICADE trial despite high pressure implantation and prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy. The PTFE-covered nitinol stent Symbiot™ (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA), was tested in the randomised trial SYMBIOT III. This study included 400 patients undergoing SVG PCI and showed no benefit over BMS but a trend towards higher TVR in the Symbiot arm at 8 months follow-up. Moreover, PTFE-covered Symbiot stent failed to show advantages regarding clinical outcomes at long-term (mean 7 years) compared with BMS. Other designs include the MGuard™ stent (InspireMD, Ltd., Tel Aviv, Israel) , covered with a PET mesh, and the O&U® pericardium-covered stent (ITGI Medical, Or Akiva, Israel) (Figure 6). Neither of these two covered stent designs have been tested in randomised clinical trials in SVG PCI. However, a small prospective trial showed a high rate of MACE (23%) in SVG intervention with the MGuard stent in terms of TLR and MI, although no stent thrombosis or cardiac death were observed up to 20 months of follow-up. Similar results were reported in other small prospective trial in which a high frequency of TLR was observed, although no case of stent thrombosis was reported. The use of Mesh- covered stents in SVG-PCI is not reflected in the current myocardial revascularisation guidelines based on the very limited experience with these devices. Due to the lack of evidence on the safety of these stent designs to prevent distal embolisation, they should not be used routinely or as an alternative to EPD’s in the setting of SVG-PCI .Covered stents, particularly of the membrane-covered type, may however be extremely useful in treating SVG perforation during PCI, (Figure 5). Atherectomy has also been tested as an alternative method to prevent atheroembolisim. However, in spite of initial reports supporting this approach, more updated evidence referring to the transluminal extraction catheter and the X-Sizer devices do not support its use in SVG recanalisation, .

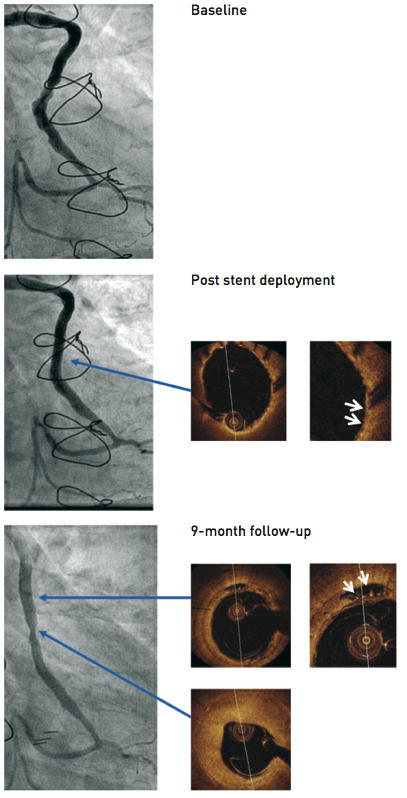

Figure 6

A PET-mesh covered stent (MGuard) was implanted with concomitant use of a FilterWire distal embolic protection device. The angiographic images obtained before, immediately after PCI and at 9-month follow-up are shown. Optical coherence imaging immediately after the procedure shows embedment of the stent struts in the soft friable atheroma and the scaffolding effect of the PET mesh. At follow-up the patient was asymptomatic, and non-invasive testing did not disclosed myocardial ischaemia. There was localised luminal loss inside the stent, causing a non-significant stenosis. Intracoronary imaging with OCT demonstrated heterogeneous vascular responses to the implantation of the stent, with predominant neointimal hyperplasia at the site of minimal luminal diameter and localised areas of late appearing stent malaposition in angiographically normal segments. The thin PET filaments are visible within these areas of malaposition.

[Case courtesy of Eulogio García, Hospital Clinico San Carlos, Madrid, Spain]

Regarding medical treatment during SVG PCI, it seems that intensive antithrombotic treatment with the use of the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor abciximab in an attempt to prevent thromboembolic events, do not improve clinical outcomes but increase the risk of major bleeding .

USE OF BARE METAL AND DRUG-ELUTING STENTS IN SVG

A number of studies have addressed the different stent types used in vein graft interventions. The SAVED trial, which compared in a randomised fashion the use of the Palmar-Schatz stent and balloon angioplasty in 220 patients with SVG stenosis, demonstrated that coronary stents were more effective than balloon angioplasty in this indication. Of note, the restenosis rate for stents implanted in SVGs was substantially higher than in native coronary vessels, with a >30% restenosis rate after BMS treatment of SVGs, which was confirmed in further studies. The introduction of drug-eluting stents appeared to offer a solution to this problem.

A large number of studies have previously shown the superiority of DES over BMS in SVG PCI to reduce the rates of mortality, TLR and TVR without increasing the risk of MI and stent thrombosis , , , , , ,Recently however, a growing body of evidence calls the long term benefits of DES over BMS into question. The initial results from ISAR-CABG (Is Drug-Eluting-Stenting Associated with Improved Results in Coronary Artery Bypass Grafts) trial showed superiority of DES over BMS in terms of death, MI and TLR at 1 year . The advantage of using DES was lost at 5 years owing to increased rates of TLR in the DES group . Conflicting results are also noted in the available long term follow up of two smaller trials, with one trial suggesting sustained superiority of the DES over BMS, whilst the other proposed the loss of efficacy of DES in the longer term. , It should be noted that current ESC guidelines recommend PCI via the bypassed native artery as the favoured approach and to consider PCI to the vein graft when this is not feasible or in the case that the PCI via the bypassed native artery has failed. The same guidelines also recommend the use of DES for all PCI interventions.

Several pathological characteristics of SVG attrition have to be taken into consideration when analysing safety and efficacy of stent use in this context. Atheroma in SVGs frequently presents extensive areas of necrotic core, which may interfere with endothelialisation and neointimal coverage of BMS and DES struts. In addition, the long-term benefit of stenting may be limited due to progression of attrition or thrombus formation in non-stented segments of the SVG, which occur as part of the natural history of SVG degeneration.

Finally, treatment of stent restenosis in SVG is safer than treatment of de novo stenoses. This is due to the different pathological substrate, which in the case of restenosis does not cause the feared atheroembolism characteristic of de novo SVG atheroma.

PCI IN INTERNAL MAMMARY AND RADIAL ARTERY GRAFTS

The pathological substrate for luminal narrowing in the internal mammary artery (IMA) grafts is completely different from saphenous vein attrition. In most cases, luminal narrowing is the result of neointimal hyperplasia secondary to vascular trauma during graft preparation and anastomosis. Percutaneous treatment of IMA grafts is, therefore, not fraught with the risk of atheroembolism described above in SVG PCI. Currently, there is little evidence regarding the best percutaneous interventional approach for treating the late IMA graft failure. In many occasions, IMA stenoses respond favourably to balloon dilatation. The overall success of balloon angioplasty in this setting, according to a review of more than 1,000 published cases is around 90%. Stents may be needed in case of dissection or suboptimal results of balloon angioplasty, with similar results using BMS and DES, . An observational study of patients with IMA failure treated with different DES have shown a relative low event rates for IMA PCI at long-term (mortality 16.5% at 41 months, 9% from cardiac deaths, 7.5% from noncardiac causes), and 11.5% of patients needed a repeat revascularisation.

Little information is available on the treatment of stenoses located in radial artery grafts. Focal stenosis of radial artery grafts is a rare angiographic finding and its meaning is uncertain, since in this type of graft spam occurs frequently as a response to manipulation during catheter engagement. It has been recommended that PCI with balloon alone should be restricted to the early postoperative period during which spasm is difficult to exclude, while leaving stenting for subacute settings, on the grounds of excellent and durable results.

PCI IN NATIVE CORONARY ARTERIES IN PATIENTS WITH PRIOR CABG

As discussed above, percutaneous treatment of stenoses located in native vessels constitutes a frequent alternative to re-do CABG. Long-term failure of SVG more frequently affects the right or circumflex coronary artery with concomitant patency of an IMA graft to the LAD. In these cases, PCI of the by-passed native vessel should be the preferred approach whenever feasible, due to the inherent high risk of PCI complications, the accelerated rate of atherosclerosis observed in SVGs and the high frequency of TLR in this subset. In fact, this is reflected in the current guidelines. The little evidence we have today comparing native vessels vs grafts PCI in prior CABG patients comes from observational studies derived from registries, showing that most percutaneous interventions are done in the native vessels, with a higher rate of in-hospital complications in graft PCI patients, including mortality, but with similar post-procedural clinical outcomes , , A recent observational study found a worse long term result of PCI in SVG compared with PCI in native vessels, with target vessel revascularisation being 5 times higher in the SVG PCI group . Another large registry study demonstrated that in comparison to native coronary PCI, PCI in bypass grafts was significantly associated with an increased incidence of short and long term major adverse events. This included more than twice the rate of in hospital mortality, a 61% higher risk for MI and 60% higher risk for repeat revascularisation during long term follow up. In other cases, the target stenosis may be located distal to the anastomosis of a patent graft, as a result of atheromatous progression in the distal vessel (Figure 7).

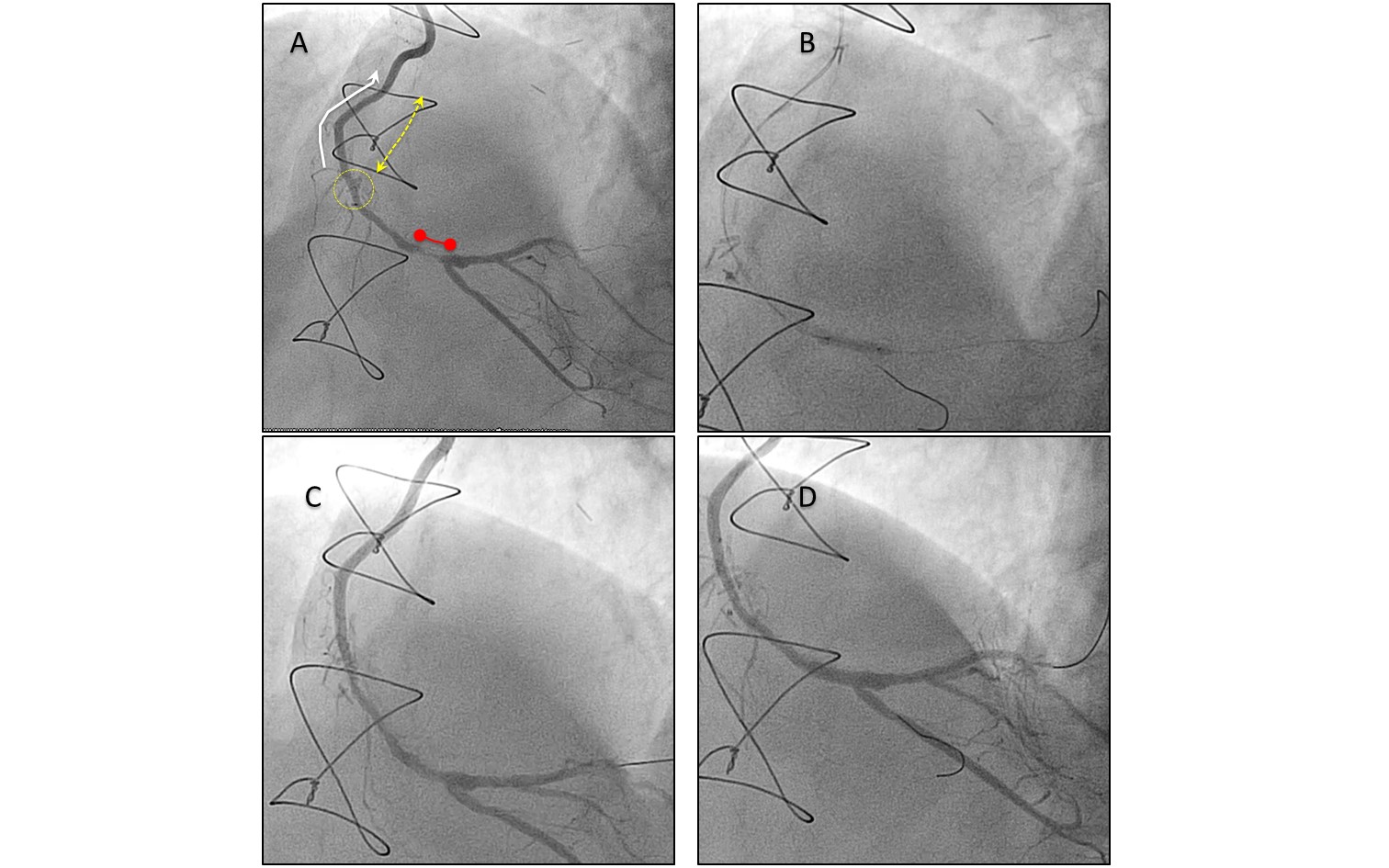

Figure 7

Percutaneous treatment of native vessel disease progression distal to an arterial graft

A. The figure shows an occluded proximal-mid right coronary artery (RCA) (dotted yellow arrow shows the occluded segment), treated previously with an internal thoracic artery graft (white arrow). Progression of disease of the native vessel (red segment) occurred distal to the graft anastomosis (yellow circle). The graft was patent, without obstructive disease. B. On the grounds of maintaining future graft patency, PCI was performed to the native vessel through the functional graft. Two wires were crossed to protect the bifurcation with the posterior descending artery. C. The stenosis was pre-dilatated with balloon, with good result. D. A drug eluting stent was deployed from the distal RCA to the posterolateral branch using a provisional stent technique, with a good final result .

Typically, native coronary vessels in these patients have extensive atheroma, and unfavourable characteristics for PCI such as vessel calcification - left main location and CTO are common. The main objectives of native vessel treatment after CABG are to restore vessel patency without jeopardising functional grafts, and to optimise the procedure in order to ensure long-term success. Rotational atherectomy or other plaque modifying techniques may be required to ensure stent crossing and to facilitate adequate expansion. If available, multislice CT imaging may be helpful in mapping the location of coronary calcification in investigating the characteristics of total occlusions (Figure 8). Intracoronary imaging is strongly recommended in those patients with high atherosclerotic burden to guide the procedure and to optimise luminal dimensions. Drug-eluting stents should be considered to minimise the risk of restenosis. Guidance of wire crossing through a CTO may be performed using collateral filling from a functional graft.

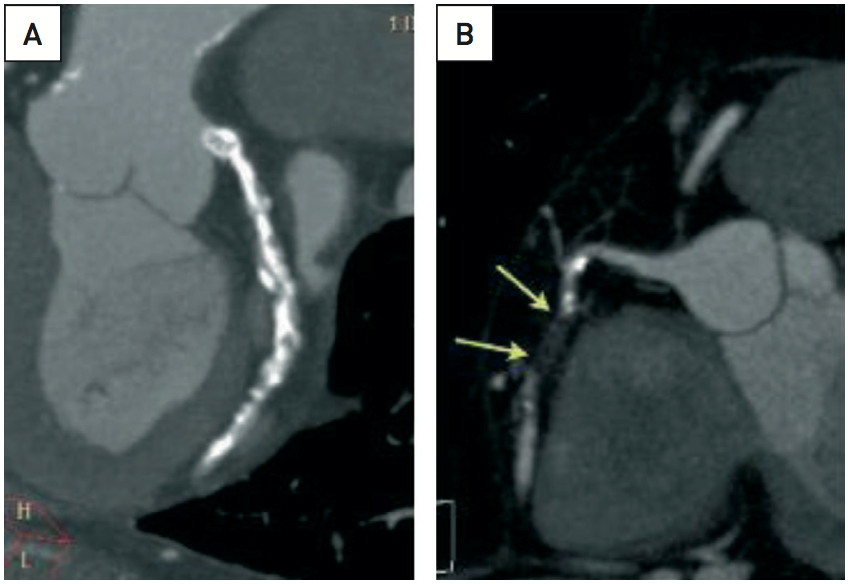

Figure 8

The added value of multislice computed tomography imaging in planning secondary revascularisation on native coronary vessels after CABG

(A) Modified coronal view using multiplanar reconstruction (MPR) with maximal intensity projection (MIP) of the left circumflex artery (LCX) in a patient with previous CABG, patent LIMA graft to LAD, occluded SVG to OM1, COPD and effort angina. Note the heavily calcified native LCX which makes the use of rotational atherectomy in treating the OM mandatory. (B) Modified lateral view with MPR and MPI reconstruction of the axial stack acquired with 64-row MDCT of an occluded RCA in a patient with prior CABG with stable angina. The RCA was patent at the time of CABG and was not grafted. Distal replenishment by collateral circulation allows an accurate assessment of the length of the occlusion. A right ventricular branch is present immediately after the end of the occlusion. The occluded segment is short, has no calcium (there is moderate calcification immediately before and after the occlusion) and follows a straight course, without bends. These are favourable features for the purpose of percutaneous recanalisation of the RCA

EARLY SECONDARY REVASCULARISATION AFTER CABG FAILURE

Perioperative ischaemic events after CABG are not uncommon, and are associated with substantial increases in morbidity and mortality, both in-hospital and in the long term. It has been shown that early graft failure occurs in up to in 12% of grafts, however only a minority of these are clinically apparent, . Myocardial injury associated with surgery may result not only from acute graft failure, but also to other perioperative causes including air or plaque embolisation and deficient myocardial protection. Several mechanisms can lead to early graft failure such as thrombosis, suboptimal or failed anastomoses, competitive flow with the native vessel, bypass kinking, conduit mechanical issues (tension or overstretching) or spasm. According to our experience and to that of other authors, around 3% to 5% of all CABG procedures undergo coronary angiography during the perioperative in-hospital stay, and there is indirect evidence that the figure has increased substantially over the last 10 years partially as a result of existing 24 hour primary angioplasty programmes in many hospitals , . Between 5% and 30% of these patients present raised myocardial damage markers, and a similar proportion of patients develop electrocardiographic changes following revascularisation procedures . In this setting, PCI plays an important role as a rescue procedure for CABG , , , , .

Patients presenting with cardiac arrest immediately after CABG do better with early re-intervention either by re-do CABG or PCI than by the non-interventional approach. Guney et al have reported that emergency revascularisation leads to a greater reduction in haemodynamic stabilisation time (p = 0.012), duration of hospitalisation (p = 0.00006), and less use of mechanical support (p = 0.003). During the mean 37 ± 25 months of follow-up period, long-term mortality (p = 0.03) and event-free survival (p = 0.029) rates were significantly in favour of the emergency revascularisation group. However, very few studies have directly compared conservative treatment, re-do CABG and bailout PCI in perioperative MI. Thielmann et al reported on 118 patients who underwent coronary angiography within the first 24 hours after CABG. There were no significant differences between acute PCI, emergency reoperation, or conservative treatment groups regarding mortality at 30 days (12%, 20% and 14.8% respectively) and 1 year follow up (20%, 27% and 18.5%). The study by Abdulmalik et al favoured PCI over re-do CABG and conservative treatment. At 1 year angiographic and clinical follow-up, these authors found a 14% restenosis rate of the target vessel in the PCI group, while 47% of the no-PCI group (including surgical and conservative treatments) were readmitted with recurrent ischaemia. Another study has shown that early intervention (PCI or CABG) may reduce the extent of myocardial damage compared with the conservative approach in patients with early graft failure. Moreover, among intervened patients, those subjected to PCI had a lesser extent of myocardial infarction compared with those subjected to re-do CABG . Only one small study has reported on the use of DES for immediate post-CABG complications. This showed that angiographic results were improved but at a cost of an increase in major bleeding complications. Our group has reported a mortality rate of 21% (15% in-hospital and 6% during the follow-up period) associated with bailout PCI after CABG .A study by Zhao et al examined the collaboration between surgeons and interventionalists in assessing the immediate results of CABG in a hybrid operating room. In the reported initial 366 procedures, suboptimal results of CABG were identified in 12% of the cases, and were corrected either by surgical revision or by hybrid PCI, with good short term results and no significant difference in operative mortality between hybrid and standard CABG (2.6% and 1.5% respectively).

It is difficult to extrapolate any conclusions from the available evidence as to whether PCI is safer than re-do CABG in this emergency context. A complex native coronary anatomy in many cases might be the reason why CABG was chosen as the method of revascularisation. The time required to organise an operating room in emergency circumstances may, on the other hand, contribute to the development of more extensive necrosis and haemodynamic instability; an accessible catheterisation laboratory can save the precious time needed to salvage the myocardium. Likewise, it is not possible to infer whether the use of DES in bailout PCI provides additional benefits. Early diagnosis of perioperative ischaemic complications and fast decision-making are of extreme importance since they influence short and long-term prognosis. Haemodynamic deterioration, pre-angiography creatine kinase-MB isoenzyme rise > 2 cut-off value and more than 30 hours between primary CABG and coronary angiography have been identified as significant predictors of in-hospital mortality in patients with perioperative myocardial ischaemia . Identification of such complications may be challenging, as ECG changes and raised myocardial markers are common after CABG; hence the need of specific criteria and diagnostic algorithms for early detection and subsequent referral for emergent coronary angiography (Figure 9).In these cases, a decisive, timely and individualised treatment strategy should be undertaken by the cardiothoracic surgeon and interventional cardiologist to limit myocardial ischemia. A percutaneous strategy in the native coronary vessel or the internal mammary graft may be feasible in certain cases. This should be avoided in saphenous vein grafts or at anastomotic sites as working with a freshly implanted graft seems to be associated with a higher risk of graft rupture or anastomotic dehiscence than in the chronically implanted setting (Figure 10). A surgical approach should be considered if there is a clear anastomotic errors, unfavourable anatomy or involvement of large territories (as is generally the case with failure of an internal mammary or left sided Y-graft)., The ESC guidelines on myocardial revascularisation recommendations for treatment of early post-operative ischemia and graft failure are shown in Table 2.

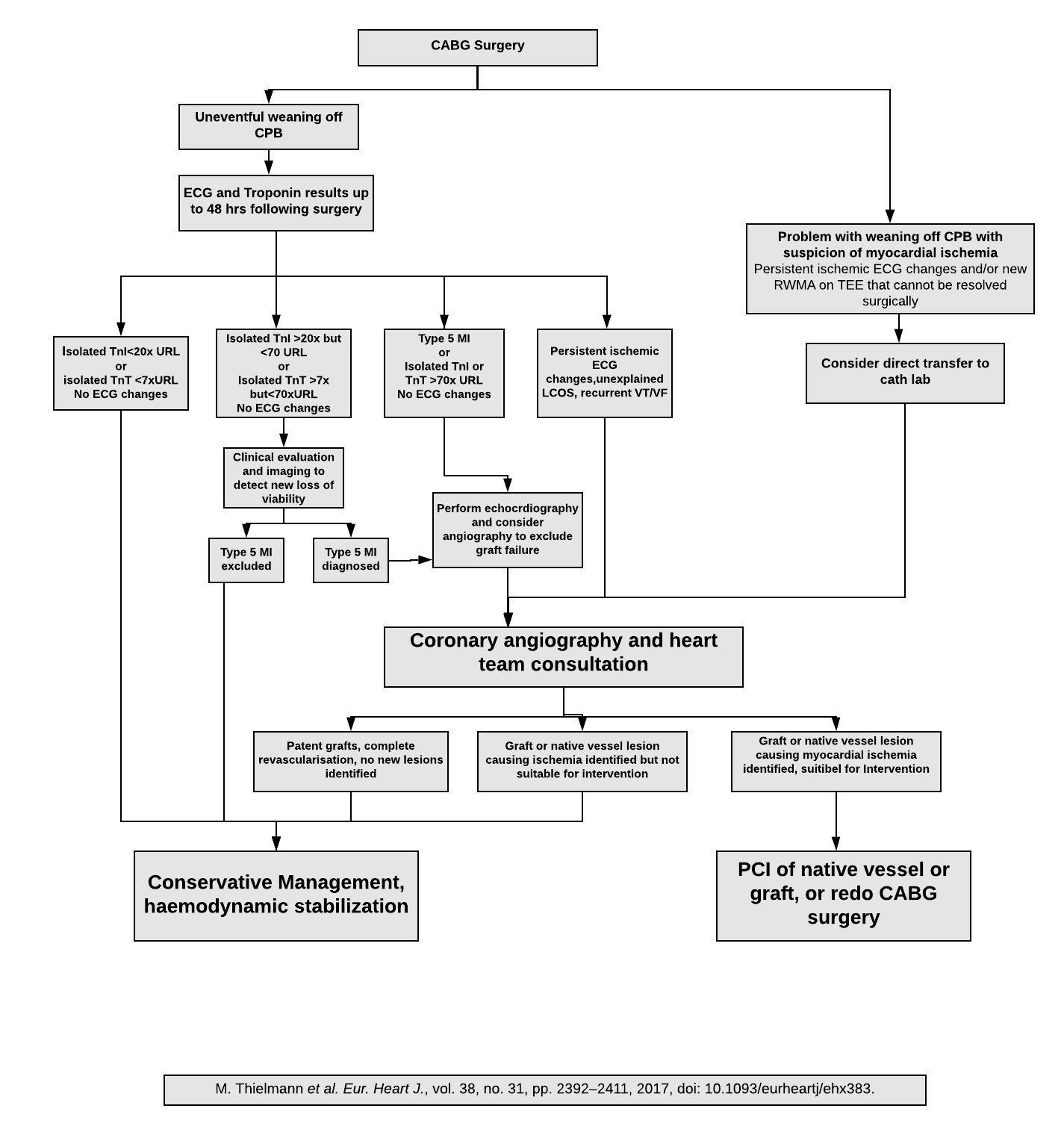

Figure 9

A suggested algorithm for the management of early CABG failure.

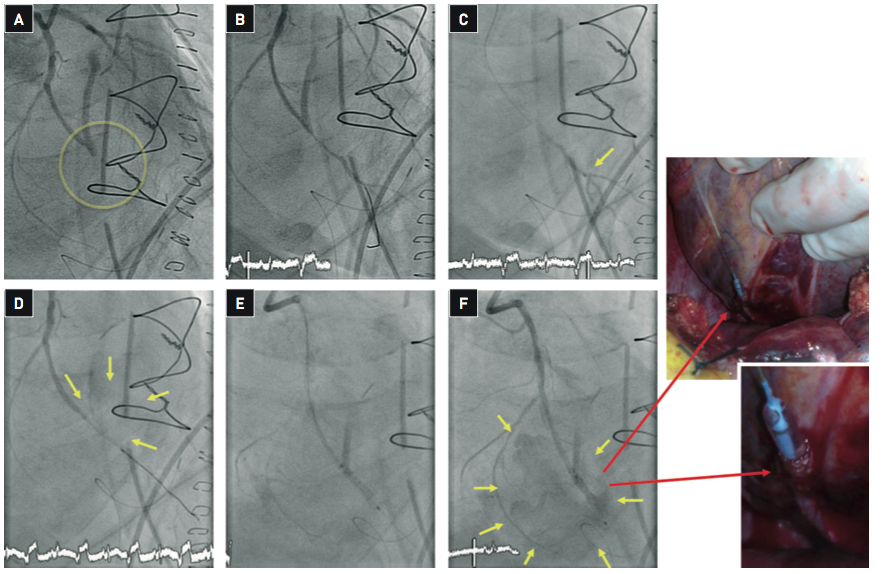

Figure 10

Percutaneous intervention for early CABG failure

Percutaneous intervention for early CABG failure has the intrinsic risk of working in recently manipulated vessels. This case illustrates the occurrence of complications in spite of a cautious approach. (A) Emergency angiography was performed in a patient with triple CABG 4 hours after surgery with the suspicion of acute closure of the saphenous vein graft implanted to the obtuse marginal (OM) branch. The vessel was diffusely diseased and surgical endartherectomy had been performed in the vessel distal to the anastomosis with the SVG graft. The OM branch was occluded and PCI through the native vessel was performed. (B) A guidewire over a Terumo FineCross intracoronary catheter was crossed through the occluded segment. (C) To verify a true intraluminal position of the guidewire, ruling out the possibility of an extravascular course through the fresh anastomosis, a distal injection through the microcatheter was performed. The distal vessel was adequately opacified. (D) Balloon dilation (2.0 mm balloon) of the occluded segment was immediately followed by important extravasation of contrast (yellow arrows) suggesting vessel rupture at the site of prior endartherectomy. Protamine was given to reverse anticoagulation. Attempts to seal the rupture with long balloon inflations (20 min) were unsuccessful. (E) A JoMed stent graft was advanced to the rupture site and implanted. Given the presence of proximal circumflex calcification, predilation was required to cross with the JoMed stent. (F) After deflation of the balloon massive bleeding to the pericardial space was documented (yellow arrows). The balloon was inflated to stop bleeding and the patient was transferred to the surgical theatre. The images taking in the surgical theatre show the extravascular location of the distal aspect of the JoStent (red arrows). Surgical repair and re-grafting was performed. The most likely explanation for this complication is that, in spite of prior verification of the intraluminal position of the guidewire, the wire went extravascular during the manoeuvring required for the passage of the stent graft.

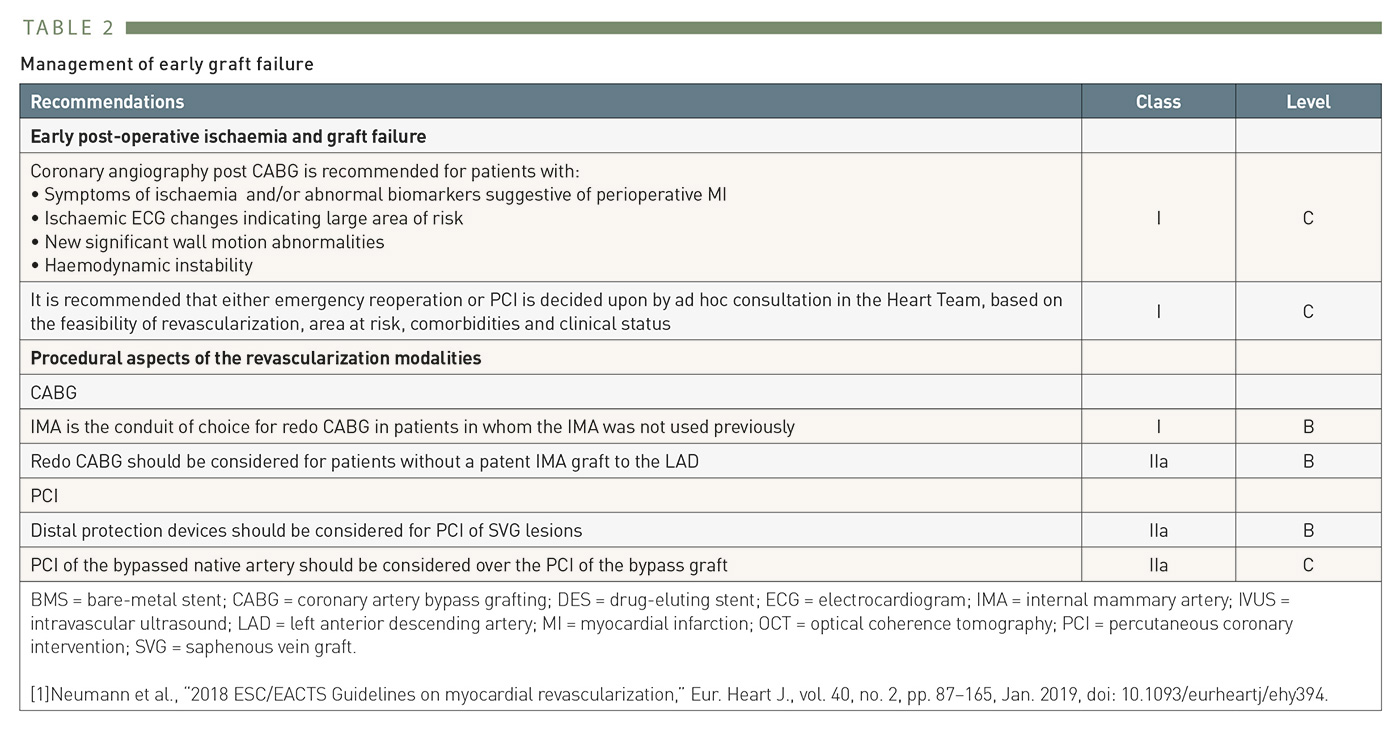

Table 2

2014 ESC Guidelines recommendations for secondary revascularisation after early CABG failure

Crossed secondary revascularisation in patients with prior PCI

CABG FOR EARLY PCI FAILURE

The advent of coronary stents allowed a more successful management of acute vessel closure during PCI. Consequently, a six-fold decrease in the need for emergency CABG for early PCI failure over the period 1993-2003 was reported . In the contemporary stent era, the incidence of emergent CABG for PCI failure is close to 0.2%, . In fact, most of PCI complications can be successfully managed in the catheterisation laboratory. Currently, for early PCI failure, the mortality and emergent CABG rates do not differ between centres with or without on-site surgical backup . Cardiopulmonary assistance may be considered if the patient does not stabilise prior to emergency CABG.

CABG FOR LATE PCI FAILURE

More frequently, CABG may be required as a consequence of the long-term failure of a PCI procedure, mainly due to restenosis, or to progression of native vessel disease with new stenoses. A large meta-analysis published in 2014 has reported a frequency of 12.2% of CABG in patients with prior PCI .

Not infrequently, restenosis of an implanted stent may lead to crossed surgical revascularisation if complete revascularisation was not achieved during the first procedure (by not treating, for example, a CTO, limiting stenting to a non-occluded vessel). Until recently, there was a tacit consensus that in most of these cases, PCI could be used in such situations as a method of “provisional revascularisation”, leaving open the possibility of future CABG if PCI was unsuccessful. However, this attitude failed to take account of the lack of evidence on the outcome of CABG in patients previously treated with PCI, and it has been challenged by several studies reporting on the predictive value of prior PCI in the development of major cardiac events, including death, after coronary surgery, , , , , .

There are no randomised trials examining the effects of prior PCI on subsequent outcome in patients undergoing CABG. Data in this regard comes from several large observational studies, and particularly in propensity matched patients, reporting that prior PCI increases both in-hospital mortality and MACE by an odds ratio of two to three-fold. The reasons for this interaction remain unknown. Several studies have suggested that coronary stenting may have a detrimental effect on endothelial function in the distal coronary bed, , . This has been shown for DES, whereas most of the patients in the studies linking prior stenting with poorer outcome after CABG had been treated with BMS. A second cause might be the existence of long vascular segments covered by stents, the so-called “full metal jacket”. This might be supported by the fact that some studies have reported significantly fewer surgical grafts implanted at the time of the operation in patients with prior coronary stenting. In a large systematic review including 8358 patients from 9 studies with prior late PCI failure who underwent CABG, it was found a higher risk of re-sternotomy for bleeding and 30 day in-hospital mortality compared with those patients who underwent CABG without prior PCI, but late outcomes were similar between both groups.

However, some other data challenges the aforementioned studies. A large Japanese observational study analysed data from 48051 consecutive patients who underwent isolated, elective CABG between January 2008 - December 2013 . 25.9% of these patients had prior PCI. This study found that patients with prior PCI had no significantly higher risk of operative mortality or composite outcome (operative mortality and major morbidity), compared to patients without prior PCI. Another study in 13,184 patients who underwent CABG (11,727 had no prior PCI and 1,457 had prior PCI) found that prior PCI was not an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality . It should be emphasised however that long term follow up and RCT data is needed in this area. As outlined previously, a heart team based approach is best in this setting.

The potential occurrence of longitudinal interactions between coronary interventions has probably been underestimated. It appears reasonable to think that operator awareness of these interactions and of the probability of future need of CABG, so far rarely expressed in an explicit fashion in any document, may lead to a shift in attitude at the time of planning coronary stenting, avoiding merely episodic care. The confirmation of an interaction between implanted metallic stents and subsequent surgical revascularisations would constitute an additional argument in support of re-absorbable scaffolds, , which may not compromise surgical access to the coronaries in case of disease progression.

Role of imaging and intravascular techniques in secondary revascularisation

Cardiac imaging plays an important role in planning secondary revascularisation. Coronary arteriography has been the gold standard in the assessment of native coronary circulation, surgical grafts and implanted stents, and continues to be the most widely used imaging technique for this purpose. The strength of this procedure is that it provides high quality images. However, after CABG, the diagnostic power of coronary angiography also diminishes, since selective catheterisation and complete opacification of surgical grafts is not always achievable. Furthermore, the technique has further associated risks, derived from patient profile and technical difficulties. Catheter manoeuvring may damage supra-aortic vessels during selective catheterisation of thoracic arteries. Given the presence of more extensive atherosclerosis in these patients, increased catheter manipulation implies a higher risk of cholesterol embolism. Procedure-induced kidney failure may occur as a direct result of this, but also as a result of the larger amount of contrast given during angiography and aortography. These risks are exacerbated in the high number of diabetic patients requiring secondary revascularisation.

In this regard, multislice computed tomography (MSCT) is a valuable tool in the study of patients with prior CABG . Although in many cases MSCT may be followed by invasive coronary angiography, the information obtained with MSCT makes possible a more selective study, restricting invasive imaging to native segments in which the sensitivity and specificity of MSCT is lower due to vessel calcification, blurring, etc. MSCT–assisted intervention is already a reality in fields like magnetic navigation, and it is foreseeable that in the near future co-registration of MSCT and angiography may be available in many catheterisation laboratories, helping to perform PCI based on MSCT images, as it has been performed in magnetic navigation (Figure 4), helping specially in complex cases such as CTO, tortuous arteries and bifurcation lesions , , . MSCT also provides important anatomical information for re-do CABG, such as the relationship of cardiac structures and previous grafts to the sternum, which may be used in formulating preventive measures, such as tailored modalities of sternotomy, or the planning of cannulation and administration of cardioplegia prior to cardiopulmonary bypass . These advantages translate into shorter procedural times, fewer blood transfusions, shorter stays at intensive care units and less frequent perioperative infarction in those patients studied with MSCT prior to re-do CABG, compared with those without MSCT , , . The 2010 Appropriateness Criteria for Cardiac Computed Tomography identified the use of MSCT before re-do CABG as an "appropriate" indication . One of the key aspects to be evaluated in CABG patients prior to repeat cardiac surgery is the location of the grafts, which must be located > 10 mm from the sternum to minimize the risks associated to the sternotomy procedure.

In cases with previous stent implantation, diagnosis might also benefit from using techniques other than conventional angiography. This is the case in assessing restenosis, which is currently feasible with MSCT in large vessels, such as stented left main coronary arteries and surgical grafts (with the advantage, for example, of avoiding the risk of catheter damage to left main stents deployed partially outside the vessel, protruding into the aorta) , and in general with vessels ≥ 3 mm diameter in which MSCT have shown a high accuracy for evaluation of in-stent restenosis. Moreover, MSCT have been used to investigate the incidence of neointimal proliferation and silent in-stent restenosis in asymptomatic patients, showing a good overall accuracy compared with invasive angiography, and a higher incidence of neointimal proliferation in patients with diabetes. This imaging technique could probably be applied to vessels of a smaller size in the near future. With this goal in mind, awareness of the desirability of non-invasive imaging of coronary stents with MSCT could lead to technological developments, both in MSCT and in stent designs. A recent novel technique, subtraction coronary computed tomography angiography, has shown promising results in addressing some limitations of conventional MSCT. The subtraction method enables the removal of calcium and coronary stents from the images, allowing a better evaluation of in-stent restenosis and severe calcified segments after remove the artefacts, even for stents with a diameter of 2.5-3 mm . However, a longer breathing time and a higher radiation dose than in conventional MSCT are some of the pending issues of this approach.

Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) and optical coherence tomography (OCT) may be used to investigate underlying substrates or mechanisms which might have contributed to the development of restenosis, such as stent under expansion, collapse or fracture, or the presence of calcified plaque, and this may prove to be important in a redo procedure , , , , . In this setting, OCT has shown a higher accuracy than IVUS after stent implantation to detecting the underlying mechanisms of PCI failure, and may be used to guide and optimise the re-PCI , , , Besides this, coverage of side branches, assessment of luminal size and other aspects of interest can be optimally assessed with this technique or with more recently available OCT probes. Assessment of myocardial ischaemia and viability is another key issue in planning secondary revascularisation. Since the sensitivity and specificity of EKG exercise testing decreases significantly after coronary interventions, the use of functional imaging techniques, such as exercise or stress scintigraphy or echocardiography, capable of both detecting and locating myocardial ischaemia, has been recommended . Magnetic resonance imaging, which allows differentiation of viable myocardium from scar areas, may prove of particular use in these patients A more selective functional assessment of stents, surgical conduits and native vessels can be performed using pressure guidewire measurements with a spatial resolution not achievable by non-invasive means (Figure 11). FFR-guided PCI of bypass grafts have shown to be safe and accurate, and provides better clinical outcomes compared with angio-guided PCI at long-term follow-up .

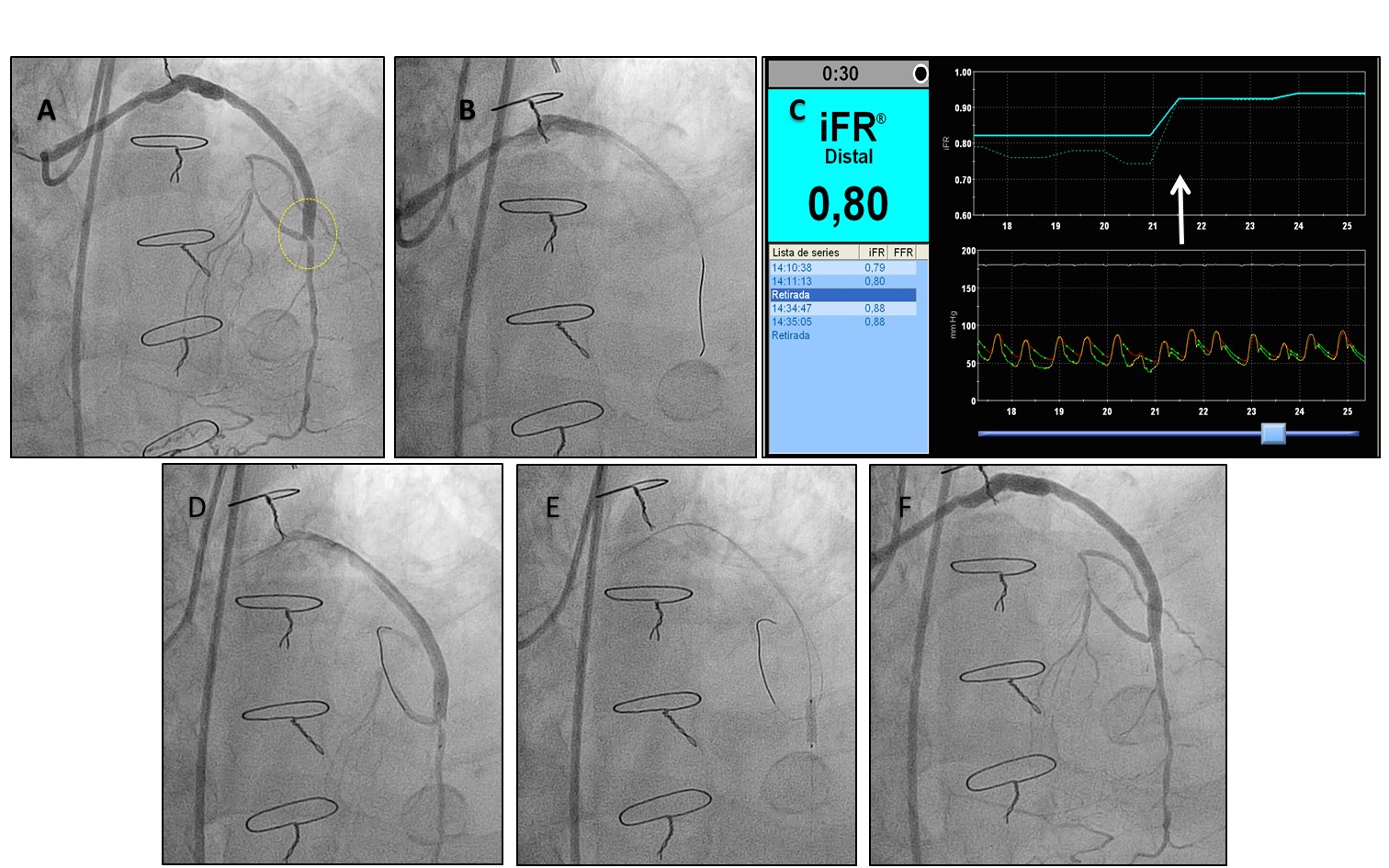

Figure 11

iFR-guided revascularisation of a stenosis located at the coronary anastomosis of a saphenous vein graft.

A. The panel shows a left anterior descending artery (LAD), with prior chronic total occlusion treated with insertion of a saphenous vein graft 7 years before. The graft was patent and without diffuse disease, but presented a stenosis at the distal anastomosis (yellow circle). B. Functional assessment with pressure wire (iFR mapping) was performed to assess the haemodynamic relevance of the stenosis and the contribution of distal irregularities in the LAD to pressure drop. C. The estimated iFR was 0.80 in the mid LAD segment, indicating that the stenosis was haemodynamically severe. The pressure wire was pulled back demonstrating that the pressure gradient was located at the anastomosis lesion (white arrow), ruling out the contribution of diffuse LAD narrowing to impaired coronary conductance. D, E. PCI was performed through the functional graft and limited to the stenosis located at the anastomosis. An additional wire was used to protect the segment of the LAD proximal to the anastomosis. A drug eluting stent was successfully deployed. Taking into account the difference in diameter between SVG and the native vessel, the proximal portion of the stent was post-dilatated with a larger balloon, with a good final result (F).

Conclusions

Secondary revascularisation is the ultimate proof that coronary interventions are not isolated events, but rather part of the cardiovascular biography of patients. In the recent past, decisions on secondary revascularisation were frequently taken ad hoc and unilaterally. One of the main risks of this attitude is that it leads to episodic care, which lacks a longitudinal perspective and does not take into account the potential of future coronary revascularisations. From this point of view, coronary revascularisation should be considered as a care process rather than a series of single interventions, including such aspects as secondary prevention. A renewed multidisciplinary approach, free from any association with former conflicts, must be promoted. The current scenario of changes in cardiovascular medicine and health care may provide an opportunity for undertaking such process – the re-engineering of coronary revascularisation.

Personal perspective - Javier Escaned

The term secondary revascularisation emerged in response to the lack of a recognisable category grouping all the available knowledge on different aspects of diagnostic and therapeutic management of patients undergoing repeat coronary interventions. Patients with revascularisation failure typically present a higher cardiovascular risk profile and more frequent co-morbidities. Establishing the causes of revascularisation failure is key in planning new interventions and requires proficiency in non-invasive and intracoronary imaging techniques. Not seldom, repeat revascularisation presents specific challenges to the operator derived from anatomic or patient complexity. Due to this, decisions on secondary coronary revascularisation should be ideally taken in the context of a fully integrated heart team which include cardiac surgeons, interventional cardiologists as well as clinical cardiologists.